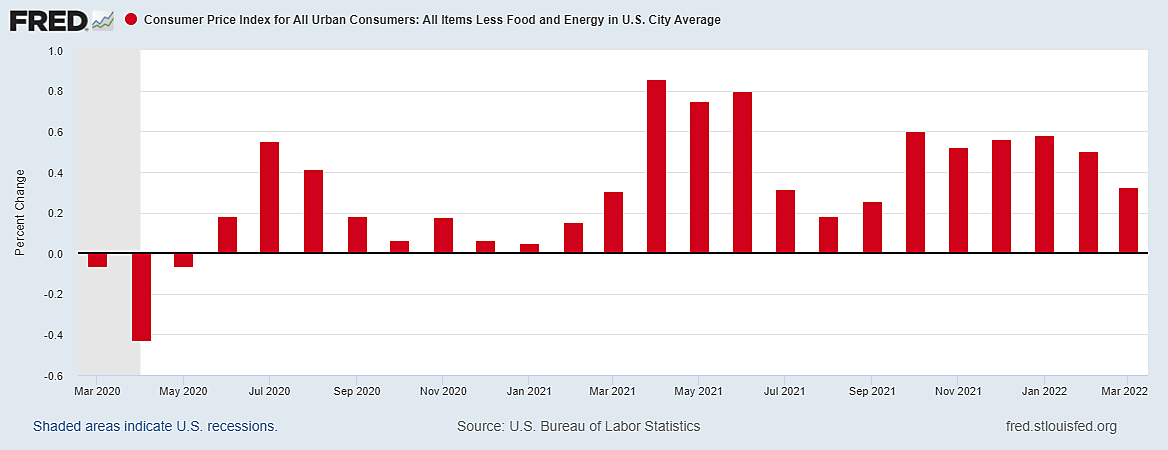

After stripping out direct energy and food prices, the core consumer price index rose only 0.3% in March – down from 0.5% in February and 0.6% in January. The graph shows that core inflation was highest in the second quarter of last year, when it rose by 0.8% a month.

Asked at a press conference why he thought year-to-year inflation numbers would slow down this spring, Fed Chairman Powell said that was partly because of the “base effect.” Because inflation was so high in April-June of last year, the 12-month change this year will be calculated from that high 2021 base. “Really what we’re looking for, though, is month‐by‐month inflation coming down,” he added. With core inflation that is exactly what we are seeing so far in 2022.

The special reason for emphasizing core inflation right now, of course, is Russia’s war on Ukraine, which has reduced world supplies of both food and energy and raised their prices. But higher prices for oil and natural gas pervade costs of producing and distributing many things outside the narrow “core” definition of direct household energy costs. Even aside from war disruption, prices of food grain and livestock feed would still be heavily affected by high energy costs involved in farm fertilizer, fuel, and transportation.

Former Fed Vice-Chairman Alan Blinder recently wrote, “The bloody conflict in Ukraine is already driving food and energy prices higher, which will boost headline inflation in the coming months. Core inflation won’t be immune because food and energy prices seep into virtually all other prices, albeit in muted form. What product doesn’t include energy in its cost, either directly (to keep the lights on) or indirectly (via delivery trucks)?” He is certainly right about rising oil prices affecting even core inflation, which suggests the March increase in core inflation would have been even smaller than 0.3% were it not for the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Higher prices of crude oil and natural gas from Russia’s brutal war, on top of sustained loss of U.S. and foreign oil production capacity during deflationary 2020 lockdowns, have apparent inflationary effects on “headline” inflation numbers which includes food and energy. But because household budgets are limited, paying more for food and energy leaves less income to spend on other things. And that, in turn, makes it more difficult for those producing or marketing nonfood and nonenergy goods and services to raise prices without a crippling loss of sales. The loss of household wealth from the falling value of their bonds and stocks is another factor restraining consumer demand and therefore producer pricing power.

Household surveys of expected future inflation naturally reflect the headlines, so expected inflation is a lagging indicator of observed inflation news. Expected inflation surveys neither explain nor predict actual inflation, but actual inflation does explain the surveys.