Weeks after a 3.75% rise in metro fares in Santiago, Chile sparked violent protests by a small group of students that then generated more widespread disruption, mostly peaceful mass protests continue. Some observers have seized on the political crisis to make often-repeated claims that Chile’s free-market model has generated growing inequality and been fundamentally unjust despite having produced greater wealth.

Yet such claims are difficult to square with the facts. Since its free-market reforms began in 1975, Chile has quadrupled its income per capita, making it the most prosperous country in Latin America. Chile’s improvement on the whole range of indicators of well-being—e.g., maternal mortality, access to proper sanitation, etc.—is impressive, and the country consistently outperforms the region. It has the highest rating among Latin American countries on the UN’s Human Development Index (and ranks 44th in the world); it has the best educational system in the region as measured by student performance; and it does not just have one of the freest economies in the world, it has the highest levels of overall freedom, including civil and personal liberties, in Latin America.

The Fall in Inequality

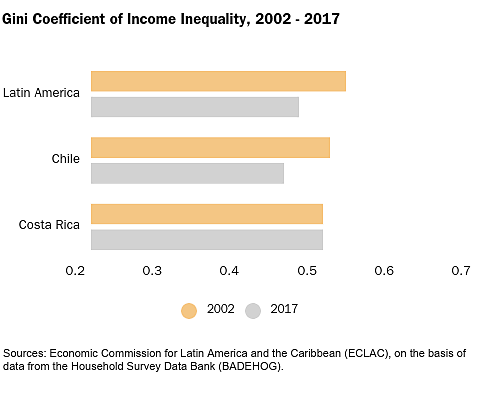

Chile’s growth has allowed it to reduce its poverty rate from more than 45% in the 1980s to 8.6%, and to create a large middle class. The country’s income inequality, which has been high for hundreds of years, has been falling considerably since the 1990s, according to the World Bank, and is lower than the Latin American average according to the UN’s Economic Commission on Latin America. Costa Rica has greater inequality than Chile. (See graph). A Harvard study by Rodrigo Valdés, a finance minister of former socialist President Michelle Bachelete, found that from 1990 to 2015, the income of the poorest 10% of Chileans increased by 439%, while that of the top 10% went up by only 208%.

Studies by Catholic University professor Claudio Sapelli confirm a closing inequality gap in income and other indicators. Controlling for age and other factors, Sapelli furthermore finds that income inequality within generations (inequality within the same age cohort) is lower among younger generations than among older generations. That means that as the country matures, its overall income inequality goes down, as we have observed. Unlike developed countries, rapidly developing Chile has notably different levels of inequality per generation given the greater opportunities available to younger Chileans. For example, the number of students enrolled in higher education has increased by a factor of 10 since Chile’s reforms began.

Compared to developed countries, a status that Chile is close to reaching, income inequality is high (though it is about average in terms of income before taxes and government transfers). For that reason, some advocate increasing taxation and distribution. Setting aside the effects on growth and opportunity that bigger government in Chile would have, Sapelli’s findings indicate that the country is already on a path toward continued decreases in income inequality that will put it in the same range as that of other developed countries in the not-too-distant future. (Using the standard Gini-coefficient measurement of income inequality, Sapelli estimates that Chile will have a Gini score of 0.35, indicating a lower inequality than that of Spain or the United States, for example, and slightly higher inequality than Canada’s 0.34).

High Social Mobility

Numerous studies have also documented Chile’s high social mobility. The OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) found that 23% of children born to fathers from the bottom quartile of income earnings move up to the highest quartile of earnings. Chile outperforms all other OECD member countries (made up mostly of the world’s rich countries) in this regard. Chile’s upward mobility from other quartiles also compares favorably to rich countries, according to the OECD, and it is one of the countries that shows the most downward mobility from the highest quartile.

Using income deciles, Sapelli finds similarly high levels of income mobility. For example, over a ten-year period, the majority of those who were in the top decile have fallen to lower deciles, while 71% of those who began in the bottom decile have moved up to higher deciles. Sapelli finds a high degree of intra-generational mobility (mobility within the same generation) as well as inter-generational mobility (social status of one generation compared to another). For example, only 40% of Chileans aged 55–64 have had secondary education, compared to 85% of those aged 25–34, a figure that compares favorably to rich countries. After reviewing the evidence, Sapelli concludes that “Chile is a more socially mobile country than France, the United States, and Germany.”

Causes of Discontent

If Chile’s progress has been so impressive, what explains the protests? Many on Chile’s political left are interpreting the unrest as a rejection of the market model that the right has imposed on the country. But that interpretation is simplistic and wrong. Chile has been a democracy for about 30 years and center-left governments have ruled the country for most of that time. The current center-right government of Sebastián Piñera came to power less than two years ago when Chileans rejected the leftist candidate in favor of Piñera’s more pro-growth, market-oriented agenda.

The causes of the current discontent are more complex and not yet fully understood. They no doubt express legitimate grievances. Growth experienced a significant slowdown during the previous government, and Piñera has not reversed anti-growth policies introduced by his predecessor nor has he been able to jump-start the economy as promised. The resulting stagnant wages combined with greater government spending and taxation without a corresponding improvement in the quality of public services has contributed to Chileans’ malaise. So have the corruption scandals that erupted during the previous government that implicated the major political parties and the business elite. Rising expectations that have gone unfulfilled are surely a part of this story.

As Alvaro Vargas Llosa explains, unlike during most of the post-Pinochet era, a good half of the Chilean left has become radicalized in recent years. It has muted voices of the moderate left with which it formed an alliance in the previous government and has strongly influenced Chile’s youth, who have grown up hearing its rhetoric that the past 30 years have been a failure. The right, center, and the moderate left have provided virtually no moral defense of the Chilean model despite its performance.

When looting and violent protests broke out, the left justified the public disturbances and encouraged such protests to continue, explicitly calling on the president to step down. Using violence as a legitimate means to influence politics would set a terrible precedent and undermine Chile’s democracy, yet it is consistent with radical left ideology and makes strategic sense. As Axel Kaiser of the Fundación para el Progreso pointed out, were the far left successful in achieving its goal, the head of the Senate, a hard-left politician, would be next in line to take over as president.

The protests can also be partially explained in a regional context. In recent months, similar unrest has broken out in numerous countries, including Ecuador, Argentina, and Honduras. Last month, the secretary general of the Organization American States condemned the role that the Cuban and Venezuelan regimes have played in instigating and fueling regional instability:

The recent currents of destabilization of the political systems of the hemisphere have their origins in the strategy of the Bolivarian and Cuban dictatorships, which seek to reposition themselves once again, not through a process of re-institutionalization and re-democratization, but through their old methodology of exporting polarization and bad practices, to essentially finance, support and promote political and social conflict.

Venezuelan dictator Nicolás Maduro and the regime’s number two, Diosdado Cabello, have in recent weeks explicitly referred to the instability in Chile and other countries as presaging a “Bolivarian hurricane,” in reference to Chávez-style socialism, and as part of the plan of the Sao Paulo Forum, the alliance of Latin America’s far-left political parties founded by Fidel Castro to undermine the region’s democracies. Nefarious outside influence has unfortunately played some role in Chile’s protests too.

It is too early to tell how the political crisis will ultimately be resolved or to know all the factors that explain the protests. Chile’s impressive social and economic progress since the beginning of its market reforms are difficult to deny, however, and the protests can by no means be used to radically rewrite the country’s success story.