Najim Abed al-Jabouri, former mayor of Tal Afar, has a piece in the Times that seems like cause for alarm:

Both the military and the police remain heavily politicized. The police and border officials, for example, are largely answerable to the Interior Ministry, which has been seen (often correctly) as a pawn of Shiite political movements. Members of the security forces are often loyal not to the state but to the person or political party that gave them their jobs.

The same is true of many parts of the Iraqi Army. For example, the Fifth Iraqi Army Division, in Diyala Province northeast of Baghdad, has been under the sway of the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq, the Shiite party that has the largest bloc in Parliament; the Eighth Division, in Diwaniya and Kut to the southeast of the capital, has answered largely to Dawa, the Shiite party of Prime Minister Nuri Kamal al-Maliki; the Fourth Division, in Salahuddin Province in northern Iraq, has been allied with one of the two major Kurdish parties, the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan.

More recently, the Iraqi Awakening Conference, a tribal-centric political party based in Anbar Province (where Sunni tribesmen, the so-called Sons of Iraq, turned against the insurgency during the surge) has gained influence over the Seventh Iraq Army Division, which was heavily involved in recruiting Sunnis to maintain security in 2006.

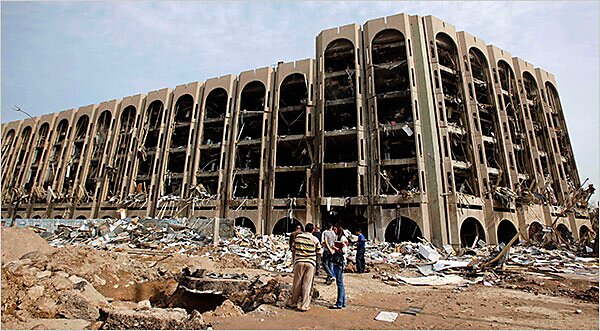

Hadi Mizban/Associated Press[/caption]

Now, via Spencer Ackerman, we find out that there may be support for al-Jabouri’s fear that “these political schisms are partly responsible for coordinated terrorist attacks like those on Sunday or the so-called Bloody Wednesday bombings of Aug. 19, which killed more than 100.” 61 Iraqi army and police officers were just arrested in connection with Sunday’s blasts, part of the effects of which you see over there on the side of the post.

Al-Jabouri writes ominously that

in a little more than two years, the United States drawdown of forces will be complete. In that time, the Iraqi security forces can go further in the direction of ethno-sectarianism, or they can find a new nationalism. True, the status quo offers a temporary balance of power between the incumbent parties, likely providing relative peace for the American exit. But deep down, ethno-sectarianism creates fault lines that terrorist groups and other states in the Mideast will exploit to keep Iraq weak and vulnerable. The better alternative is to reform and gain the confidence of Iraqis. The people will trust the security forces if they are seen as impartial on divisive political issues, loyal to the state rather than to parties, and if they embody the diversity and tolerance that we Iraqis have long claimed to be a defining characteristic.

President Bush was making a good point in 2005 when he said on al Arabiya that “the future of Iraq depends upon Iraqi nationalism and the Iraq character — the character of Iraq and Iraqi people emerging.” I think this overall point is right and fundamentally unanswered, at least according to al-Jabouri. Barbara Walter, one of the leading academics studying civil wars, wrote in August that Iraq would likely melt down if U.S. troops left, worrying about what she called “the settlement dilemma”:

Combatants who end their civil war in a compromise settlement — such as the agreement to share power in Iraq — almost always return to war unless a third party is there to help them enforce the terms. That’s because agreements leave combatants, especially weaker combatants, vulnerable to exploitation once they disarm, demobilize and prepare for peace. In the absence of third-party enforcement, the weaker side is better off trying to fight for full control of the state now, rather than accepting an agreement that would leave it open to abuse in the future.

Finally, al-Jabouri’s “better alternative” seems to amount to praying for a miracle. It’s not clear what can make Iraqis come to perceive sectarian security forces as “impartial on divisive political issues, loyal to the state rather than to parties,” and fundamentally national rather than sub-national. (Perhaps I was suckered once again by Bill Kristol when he told me in January of this year that George W. Bush’s greatest achievement was “winning the war in Iraq.”)

Given the enduring sectarianism and the relative weakness of Iraqi nationalism al-Jabouri describes, it could be interesting or even scary to see what hatches out of the egg we’ve been perched atop for the last six and a half years.

Update: I neglected to include a link to Nir Rosen’s detailed Boston Review piece on the changing nature of inter- and intra-sectarian political allegiances in Iraq. It’s definitely worth reading, for people interested in the issue.