For more than 15 years, the iPhone has embodied 21st century globalization. Apple’s signature smartphone, as well as the hundreds of subsequent competitor products, has helped billions of people around the world communicate, transact, entertain, and consume—overcoming once massive geographic, cultural, and logistical barriers along the way. The device itself, meanwhile, is a testament to the value of global supply chains and the mostly frictionless world in which they operate, thanks to major recent advancements in technology (shipping, information, logistics, etc.) and trade policy liberalization.

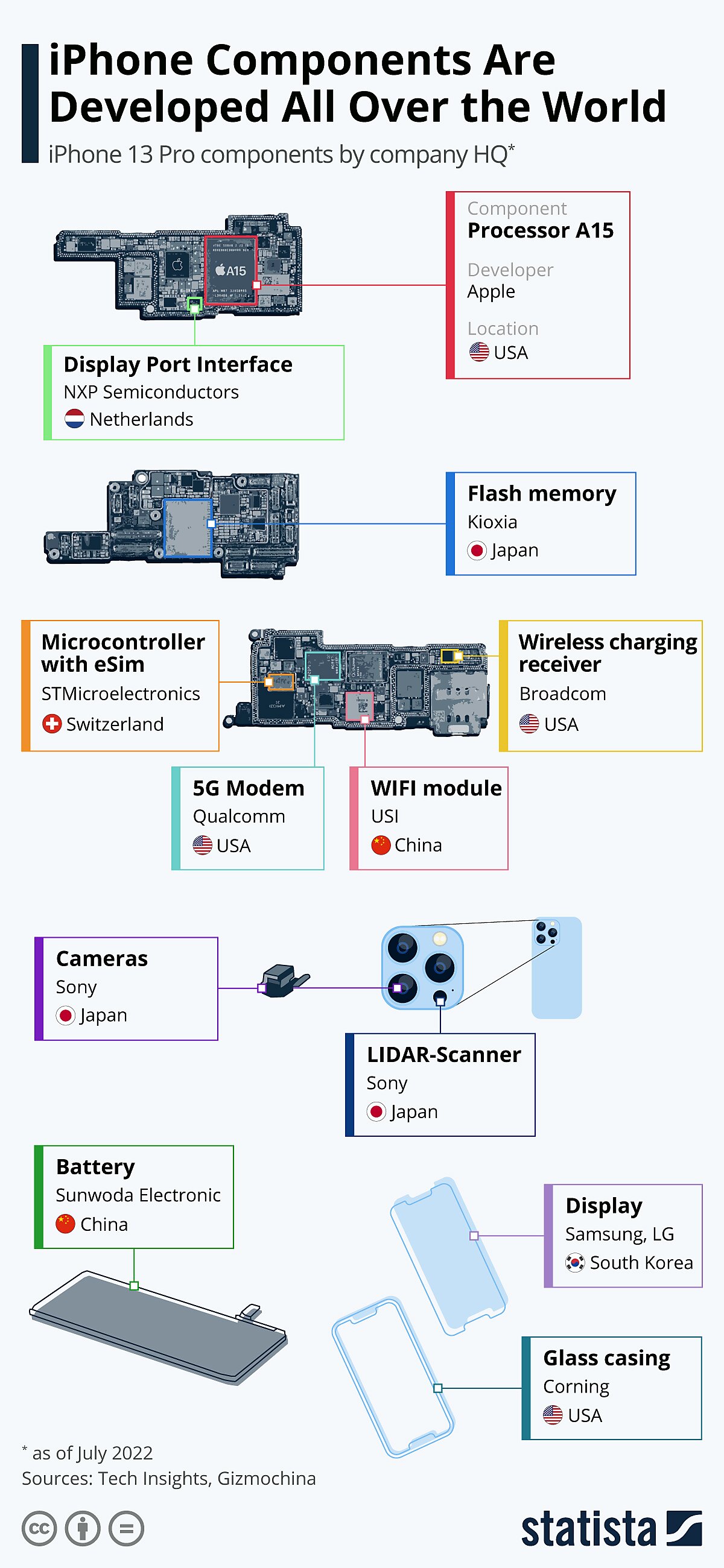

Our recent online project, “The (Updated) Case for Free Trade,” shows how past iPhone versions—each “Made in China” (according to both U.S. import statistics and the phone’s case)—were actually a global product, with the lion’s share of both production costs and final sales revenue accruing to companies outside of China. A new Statista graphic (based on information from TechInsights and Gizmochina) confirms that these trends continued for the iPhone 13 Pro:

As you can see, while certain aspects of this “Made in China” phone have changed over the years, it remains a global product and a testament to globalization. In fact, these new data undoubtedly undersell the amount of global collaboration contained in an iPhone 13. For example, Apple’s supplier list for FY2020 (published in 2021) lists companies based in 30 different countries. Previous reports further suggest that Apple sources components from as many as 200 companies, and these data omit firms and workers responsible for assembly; related production services like design, research and development, operating software, management, and marketing (most of which occur in the United States); or post-production services like transportation, retail sales, and app development. And, of course, even expanded iPhone figures omit the companies supported and economic value generated by the billions of digital trade transactions that occur through the phone itself—music, games, e‑commerce, etc.—much of which also crosses national borders with ease.

Unfortunately, many politicians and pundits today deride the policies that enable the relatively free, cross-border flow of goods and services exemplified by the iPhone and the “iPhone economy.” In so doing, they often obsess over that “Made in China” label, while ignoring all of the unseen and ever-changing economic activity underlying it. They even ignore that, per Bloomberg and others, the iPhone’s own, longstanding “made in China” label might now be changing—with some assembly of the just-released iPhone 14 (and other Apple processes) now shifting to India.

To those who follow trade and global supply chains, little of this is surprising. As we explained in “The (Updated) Case for Free Trade,” globalization critics’ static, zero-sum approach to trade policy has been obsolete for decades (if not much longer). The iPhone just continues to be one of the best explanations of why.

Maybe someone could send the critics a link to our project—via iMessage, of course.