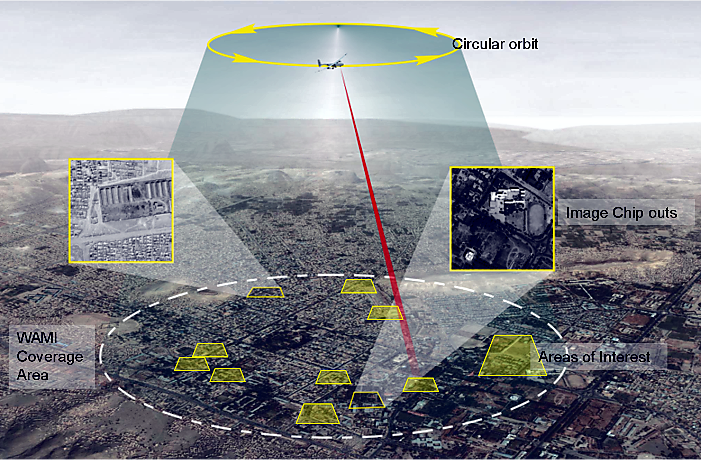

If you’re a Baltimore resident there is a chance that last year you spotted a Cessna airplane overhead at 8,500 feet. You’d be forgiven for thinking that this was nothing out of the ordinary. Yet reporting revealed that this plane was doing something extraordinary. It was carrying a persistent surveillance cameras system, allowing analysts working with Baltimore police to access what its designer calls “Google Earth with TiVo.” The surveillance cameras mounted on the airplane can cover an area of 30 square miles. With the help of the equipment police could track where suspects came from before a shooting or theft and where they went afterwards.

But the use of this surveillance technology was kept secret. When the program began the mayor, members of the city council, prosecutors, and public defenders were left in the dark.

The Baltimore aerial surveillance program is one of the most prominent recent reminders of law enforcement surveillance that can take place without public knowledge or approval.

Such secrecy is the target of a recently proposed California bill. If enacted into law the bill would require that police departments disclose information about the surveillance equipment they use on or by July 1, 2018. The bill would also prohibit police from acquiring new surveillance tools without approval from local officials.

The bill would cover “any electronic device or system primarily intended to monitor and collect audio, visual, locational, thermal, or similar information on any individual or group” including biometric tools, cell-site simulators, drones, radio-frequency identification technology, and more.

According to the bill, police departments that wish to use such gadgets would have to submit a “Surveillance Use Policy,” which will have to be publicly available and presented to local officials at an open hearing. Police departments submitting the policy will have to include not only the type of surveillance equipment in question but also the purpose of the equipment, the types of data it collects, and an outline of who is using the equipment. The bill also requires police departments to outline how they are keeping collected information secure as well as how long such information will be retained.

The obvious objection to such legislation is that it forces police to reveal their hands to criminals. After all, if police publicly disclose a new surveillance tool criminals could change their behavior accordingly, thereby becoming harder for police to surveil. The FBI used this very line of argument to justify the secrecy surrounding StingRays when outlining StingRay policies to Baltimore police.

Nonetheless, local lawmakers should seek more transparency from law enforcement when it comes to the tools they use to snoop on the public.

The least objectionable kind of surveillance involves data gathered pursuant to a warrant based on probable cause. In such cases police have reason to believe that someone is engaged in illegal activity and a judge is aware of what the police are up to. If police suspect that a man is involved in a kidnapping ring they could ask a judge to issue a warrant allowing them to wiretap his phone, thereby gathering evidence for a prosecution. In this kind of situation law enforcement identify a target of surveillance and use technology to uncover information that the suspect considers private (e.g. telephone calls).

But surveillance tools also allow police to gather vast amounts of data about the public before searching for wrongdoing. My colleague Jim Harper has labeled this kind of surveillance a “pre-search,” in which police first gather information and then scour through it to find evidence of criminal wrongdoing.

Baltimore’s aerial surveillance program is an example of “pre-searches” in action, but it’s hardly the only example. StingRays gather data on innocent people’s phone activity. Modern surveillance tools also allow law enforcement to search social media for content in a specific location, such as a protest.

Police body cameras are often presented as valuable tools for increasing police accountability. Yet without adequate restrictions in place they are valuable tools for surveillance, especially if merged with facial recognition technology. At the moment drones are comparatively rare law enforcement tools, but as drone technology improves they will proliferate and become more intrusive. Police using drones for surveillance will inevitably capture data related to law-abiding citizens. Indeed, ACLU attorney David Rocah noted that it’s inevitable that as the kind of persistent wide area surveillance technology used in Baltimore improves it will be mounted on drones.

Many people do not consider how much information about their public activities can be collected and analyzed. In her United States v. Jones (2012) concurrence Justice Sotomayor made this very point, writing, “I would ask whether people reasonably expect that their movements will be recorded and aggregated in a manner that enables the Government to ascertain, more or less at will, their political and religious beliefs, sexual habits, and so on.”

At a time when such intrusive surveillance is possible it’s important that the public is informed about their local police department’s surveillance capabilities. Some surveillance technology does only snoop on the bad guys, but we shouldn’t forget that much of government surveillance also collects data concerning peaceful and law-abiding citizens.