Low-income residents of the Twin Cities can rest easy, as planners at the Metropolitan Council, the area’s regional planning agency, are proposing a regional transit equity plan. According to the Metropolitan Council’s press release, this equity plan consists of:

- Building 75 bus shelters and rebuilding 75 existing shelters “in areas of racially concentrated poverty”; and

- “Strengthen[ing] the transit service framework serving racially concentrated areas of poverty” by building bus-rapid transit and light-rail lines to the region’s wealthy suburbs.

Bus shelters for the poor, light rail for the rich: that sounds equitable! Of course, the poor will be allowed to ride those light-rail trains (for example, if they travel to the suburbs to work as servants), just as the well-to-do will be allowed to use the bus shelters. But for the most part, the light rail is for the middle class.

As with most American urban areas, Twin Cities poverty is concentrated in the core cities. Minneapolis and St. Paul have less than a quarter of the region’s population but more than half of the poor and more than 60 percent of the poor blacks. On average, 23 percent of residents of Minneapolis and St. Paul are in poverty, compared with just 7 percent of their suburbs.

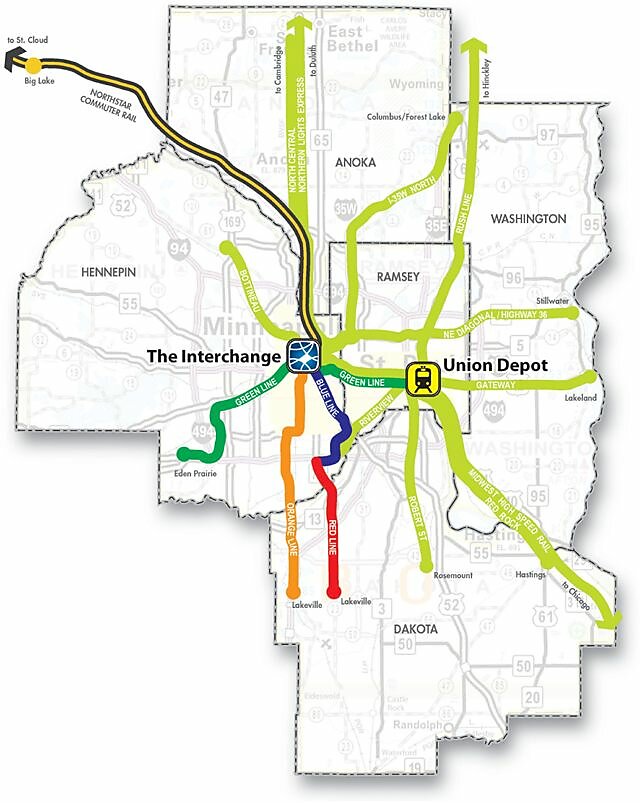

The Twin Cities’ first light-rail line–the blue line on the above map–went to Bloomington, where less than 10 percent of people are considered poor. The next light-rail line, the green line east of “the Interchange” in downtown Minneapolis, connected Minneapolis and St. Paul, but it goes from downtown to downtown through the University of Minnesota and a neighborhood that planners hope to convert into a mixed-use, New Urban community complete with creative-class yuppies, fancy restaurants, and organic supermarkets.

The next line to be built–the green line west of Minneapolis–would go to Eden Prairie, with 9 percent poverty and mean per capita incomes that are eight times the $6,000-per-person poverty threshold for a family of four. Census data indicate that 1,100 poor blacks live in Eden Prairie compared with 48,000 in Minneapolis and St. Paul.

After that will be lines to Lakeland and Lakeville, which have 4 percent poverty rates, mean per capita incomes six times the poverty threshold, and just 340 poor blacks. All the other proposed lines on the map go to suburbs with low poverty rates and high incomes.

Perhaps the only one that comes close to serving many low-income people is the proposed line going northwest from Minneapolis to an area unnamed on the map but which is actually Brooklyn Park. Brooklyn Park’s poverty rate is 11.5 percent including 3,200 poor blacks–more than any other suburb that would be served by the proposed rail or BRT lines but less than 7 percent as many as live in Minneapolis and St. Paul.

According to the 2012 American Community Survey, 13 percent of Twin Cities commuters whose incomes are below the poverty level take transit to work, while 61 percent drive alone and 14 percent carpool. Only 3 percent of Twin Cities workers live in households with no cars, and 39 percent of those drive to work (most of them driving alone, presumably in borrowed cars) compared with 37 percent taking transit. Transit clearly isn’t working for low-income people today, and it’s hard to see how a few bus shelters plus trains to the suburbs will help.

Many if not most Twin Cities suburbs are already served by express buses that are probably faster than the light-rail lines the council wants to build. On the other hand, inner-city neighborhoods tend to be served by local buses that stop frequently and therefore have low average speeds.

Let’s say bus service to the suburbs averages 20 mph and light rail can increase this average to 24 mph. By comparison, bus service in inner cities averages 10 mph and improvements can increase this to 12 mph. Which would save people the most time? Increasing speeds from 20 to 24 mph would cut one-half minute off the time it takes to go one mile, but increasing speeds from 10 to 12 mph would cut a full minute off the time to go a mile. What this means is that, to really improve transit service, transit agencies should concentrate on increasing the speeds of their slowest transit services, not ones that are already fast. That usually means inner-city buses, not suburban lines.

If the Metropolitan Council truly wanted to help low-income people, it would concentrate on improving bus service rather than building light-rail to the suburbs. But the council is apparently more interested in getting federal funds for rail transit than helping the poor. By calling this “transit equity,” it hopes that no one notices how inequitable it actually is.