In a speech at the American Enterprise Institute yesterday, House Armed Services Committee Chairman Mac Thornberry lamented the effects of the Budget Control Act’s spending caps: “the plummeting readiness levels, the long lines of equipment in disrepair, the jets that aren’t flying, and the soldiers who aren’t practicing at the rifle range.” These are problems, to be sure. The bigger problem is a general trend that has the Pentagon spending more, and getting less.

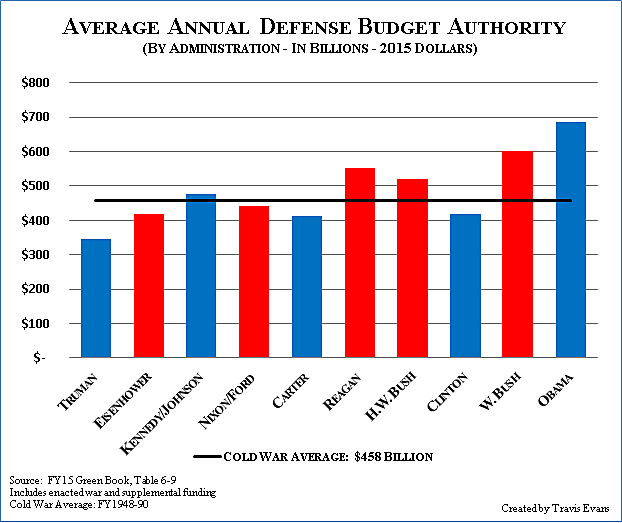

Consider the chart below, prepared by my colleague Travis Evans. Following World War II, the United States did what it had always done at a wars’ end: it demobilized. The result was a sharp and sudden decline in both military manpower and funding. From 1948 to 1950, Pentagon spending averaged $187 billion per year (all figures in 2015 dollars). Demobilization was short-lived, however. As the British and French empires retrenched and the Soviet Union expanded, the United States assumed the role of communist counterweight. Then North Korea invaded South Korea, and all hell broke loose. The primary beneficiary of the strategic shift was the Pentagon, whose budget increased by 156 percent in just one year, from $198 billion in 1950 to $508 in 1951. Large defense budgets became the norm, with spending even after the Korean armistice well above the pre-war levels.

All told, Pentagon spending averaged $458 billion per year throughout the Cold War (1948–1990). That figure includes funding for wars in Korea and Vietnam, as well as for the 1980’s arms buildup. Pentagon spending decreased steadily following the fall of the Berlin Wall, only to ramp back up as the United States embarked on the current round of post‑9/11 wars. Defense budgets under Bush the younger averaged $601 billion per year, while his successor has presided over annual budgets averaging $687 billion between 2009 and 2014. Indeed, President Obama, who was elected during an economic crisis, will leave office having approved more military spending than any presidential administration in the nuclear era. Not too bad for a president who is often accused of trying to gut the military.

To be sure, Obama inherited large and rising Pentagon budgets, and pledged to end the costly Iraq war (even as he ramped up the Afghan one — and started several others). He might have wished to dedicate even less to the Pentagon, and more to his domestic spending hobby-horses, were it not for Republicans in Congress who wouldn’t let him. Similarly, one can easily surmise that military spending under either a President John McCain or a President Mitt Romney would have been higher than what we’ve seen under Obama. But they, too, would eventually have had to contend with the messy fiscal reality: to wit, we’re broke.

The bipartisan Budget Control Act, and the dreaded sequester that it contained, may have been an elaborate gimmick either to trick Republicans into increasing taxes, or convince Democrats to approve cuts in the true drivers of fiscal imbalance: so-called entitlements. But while the BCA achieved neither of those things, it is (or at least was) bipartisan; and it has limited discretionary spending. The BCA has not, however, resulted in a precipitous decline in military spending relative to where we were a generation ago.

Less bang for the buck should not be used as an excuse for raising taxes, blowing up the deficit, or reneging on modest and sensible spending caps. If the Pentagon is getting less for every dollar spent, that is an argument for reforming bad practices — including eliminating excess base capacity, reducing the Pentagon’s bloated civilian workforce, and fixing an acquisition system that consistently delivers products late (if at all) and over budget.