While the hypothesis that tropical cyclones will become both more frequent and more intense as planetary temperatures rise has long been debated, real-world evidence has consistently refuted it (see, for example, the many reviews of this subject posted under the heading of Hurricanes at the CO2 Science website). The latest example is the work of Girishkumar et al. (2015), who examined over five decades of tropical cyclone (TC) data from the Bay of Bengal (BoB) in the Indian Ocean. Specifically, the authors “investigated how the relationship between ENSO and TCs activity in the BoB during October–December varies on decadal time scale with respect to PDO.”

Both ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation) and the PDO (Pacific Decadal Oscillation) are dominant modes of climate that operate on interannual and decadal time scales, respectively, and each has been shown to impact climate locally, remotely, and globally. The warm phase of ENSO (El Niño), in particular, has been shown to elevate global temperatures up to several tenths of a degree Celsius. Such warming provides a natural laboratory for evaluating model-based projections of CO2-induced global warming, which makes the work of Girishkumar et al. all the more intriguing, as the period of their analysis (1950–2006) allowed them to study the relationship between TCs across several ENSO cycles and one full iteration of the PDO, a cold phase between 1950 and 1974 and a warm phase between 1975 and 2006.

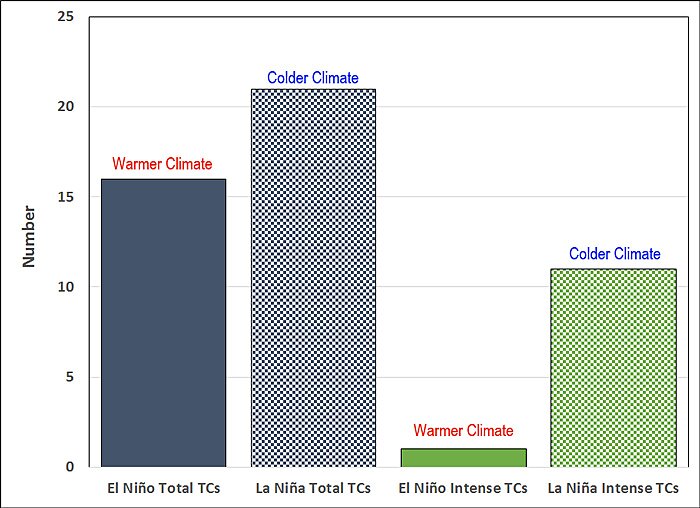

In discussing their findings, Girishkumar et al. report there was a statistically significant difference in both the total number of TCs (maximum wind speed of 34 knot or more) and intense TCs (maximum wind speed of 64 knot or more) between El Niño and La Niña years when the PDO was in the warm phase (see figure below). More specifically, the average number of total October-December TCs forming in the BoB during the eleven colder La Niña years of the PDO warm phase was 2.62 per season, whereas during the ten warmer El Niño years it was only 1.6. Similarly, but more strikingly, the number of intense TCs forming during La Niña amounted to 1.4 per season during the PDO warm phase, whereas it was a paltry 0.1 per season in El Niño years. In contrast, during the cold phase of the PDO, the authors report “the differences in the formation of total number of TCs and intense TCs between La Niña and El Niño years are not significant.” As for why these several differences occurred, Girishkumar et al. state it is due to a significant enhancement of both low level cyclonic spin and mid-troposphere humidity that occurs during La Niña years, as opposed to El Niño years, when the PDO is in the warm phase.

October–December total and intense tropical cyclones in the BoB during El Niño and La Niña years under the warm phase of the PDO.

In conclusion, the results of Girishkumar et al.’s do not support the hypothesis that warmer global temperatures will enhance TC activity. If anything, an opposite outcome is suggested, one in which global warming will lead to fewer total numbers of TCs and fewer intense TCs. That should be good news for the millions of inhabitants living within the hurricane-prone BoB.

Reference

Girishkumar, M.S., Thanga Prakash, V.P. and Ravichandran, M. 2015. Influence of Pacific Decadal Oscillation on the relationship between ENSO and tropical cyclone activity in the Bay of Bengal during October–December. Climate Dynamics 44: 3469–3479.