Donald Trump is not backing away from his plan to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border. Here’s what you need to know about the proposal.

Public Support for a Fence or Wall

In 2013, 57 percent of likely voters told Rasmussen that they think that “the United States should continue building a border fence along the Mexican border.” In 2015, that number fell to 51 percent when asked about a “wall along the Mexican border.” CBS News asked the same question of registered voters in 2016 and found only 39 percent agreed with “a wall along the Mexican border.” Unfortunately, those surveys failed to specify the length of the fence or wall. Only 36 percent of registered voters told Pew in 2016 that they wanted to see a wall “along the entire border with Mexico.” In November, 54 percent of voters in the national exit poll also opposed to that proposal. In May, Arizona’s Cronkite News, Univision, and Dallas Morning News found that 72 percent of U.S. residents living in border cities opposed a wall.

The Wall Trump Has Proposed

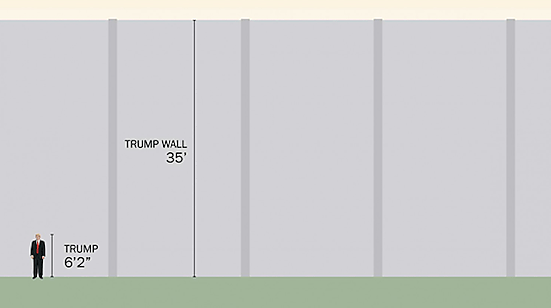

When Trump announced he was launching his campaign for president in June 2015, he said that he would build a “great, great wall on our southern border.” The U.S‑Mexico border is almost 2,000 miles, but he later clarified that the wall would only cover 1,000 miles due to “natural barriers.” As for the height, he has given estimates from as low as 30 feet to as high as 50 feet. His most common estimate appears to be 35 feet, and he said as recently as August that the wall would be between 35 and 45 feet high. Below is a Washington Post visualization of the size of a 35-foot wall.

Image 1: Size of Proposed Trump Wall

Source: Washington Post

In his plan released in August of 2015, he made it clear that this wall would not be rhetorical, symbolic, or “virtual,” but rather an “impenetrable physical wall on the southern border.” He described the wall being built out of “precast [concrete] plank… 30 feet long, 40 feet long, 50 feet long.” In August 2016, he said, “People are not going to be able to tunnel. We’re going to have tunnel technology.” He has also repeatedly promised a “big, fat beautiful door on the wall.”

Trump also insisted during his campaign that “a wall is better than fencing, and it’s much more powerful” and has called the current fence “a joke.” Despite this specificity, he admitted, when pressed in an interview following the election, that he would accept “some fencing,” but in “certain areas, a wall is more appropriate.”

The Fence That Already Exists

Image 2: Construction of U.S. Mexico-Border Fence between Tijuana and Imperial Beach, California

Source: Los Angeles Times

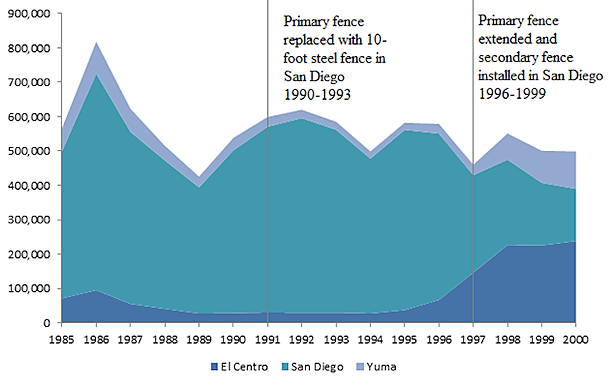

Fences were initially erected along the border in urban areas following the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986. In 1990, 10-foot-high welded steel fences were introduced along a 14-mile stretch in San Diego and soon reinforced with a second 9‑mile layer of fencing authorized by a new law in 1996. By 2000, Border Patrol had erected about 58 miles of fencing intended to deter pedestrian crossing. Almost all of it was in urban areas. Ten miles of this was reinforced with a second layer, and another 10 miles was blocked off by vehicle barriers. Above is an image of San Diego’s double-layered portion of the fence being extended into the Pacific Ocean in 2011, and the growth in the miles of total fencing is below.

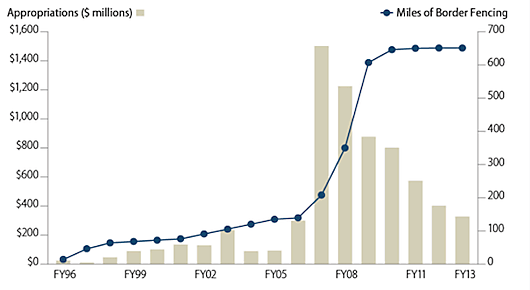

Image 3: Total Tactical Infrastructure Appropriations and Miles of U.S.-Mexico Border Fencing

Source: CRS

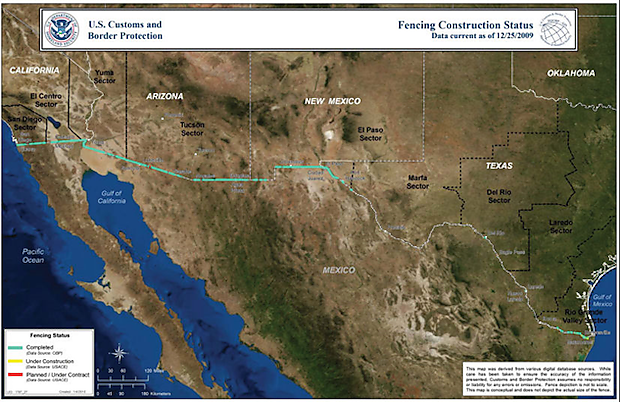

In 2006, Congress passed the Secure Fence Act, which required the creation of 700 total miles of fence. According to the Department of Homeland Security, there were 317 miles of pedestrian fencing of varying heights as of September 2015, and 36 miles of this was backed up with a secondary fence. The department met its mandate under the law by erecting an additional 300 miles of vehicle barriers. The map below shows what portions of the border have fencing. According to Border Patrol, there were 123 miles of pedestrian fencing in Arizona (of 373 total miles of border); 112 in Texas (of 1,241); 101 in California (of 140); and 14 in New Mexico (of 180). DHS has close-up maps of the fence in each state, but here’s a map of the border showing both pedestrian and vehicular barriers.

Image 4: Map of U.S.-Mexico Border with Fencing (Green)

Source: Customs and Border Protection

Even within the 300 miles of pedestrian border fence, the fence varies in height and quality dramatically depending on location. Border Patrol utilizes some half dozen different types of fencing—wire mesh, landing mat, chain link, bollard, aesthetic, and sheet piling just to control on-foot crossings (see image below). According to Popular Mechanics, these fences all vary in thickness and height from 6 feet to 18 feet. Popular Mechanics has maps that purport to show the exact locations of each type of fencing.

Image 5: Types of Fences along the U.S.-Mexico Border

Source: Department of Homeland Security

Legal Issues with Border Fences and Walls

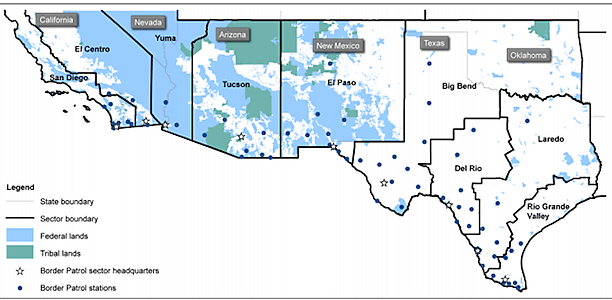

Trump promised his wall would be built “ahead of schedule.” But in order for this to happen, he will need to avoid a variety of legal difficulties that the fence builders encountered. Well over two-thirds of the border is already owned by states, tribes, and private parties. As the image below shows, almost all of the land in Texas is owned by private or state parties. Comparing the image of the locations of the current fence above to the one below, it is readily apparent that the areas where the fence was constructed almost entirely overlap the areas with federal land.

Image 6: Federal or Tribal Ownership of the United States-Mexico Border Areas by Border Patrol Sector

Source: Government Accountability Office

In 2007, as the Bush administration was extending the fence, it sent letters to property owners threatening to sue them if they did not “voluntarily” hand over their rights to their land. The letters offered no compensation for the use of the land. Some intimidated property owners signed the letters thinking that they had no recourse. Others refused, and the government sued them for access. Although the government can—and did—attempt to use eminent domain to seize property from landowners, the lawsuits took years to complete (7 years in one case), causing substantial delays.

DHS’s Inspector General (IG) concluded in 2009 that “acquiring non-federal property has delayed the completion of fence construction,” and that “CBP achieved [its] progress primarily in areas where environmental and real estate issues did not cause significant delay.” The IG report again:

For example one landowner in New Mexico refused to allow CBP to acquire his land for the fence. The land ownership predated the Roosevelt easement that provides the federal government with a 60-foot border right-of-way. As a result, construction of fencing was delayed and a 1.2‑mile gap in the fence existed for a time in this area. CBP later acquired this land through a negotiated settlement.

The IG found more than 480 cases in which the federal government negotiated the “voluntary” sale of property, and up to 300 cases in which condemnation would be sought through the courts. Because the right of just compensation is protected by the Constitution, there is little Donald Trump or Congress can do to expedite these issues.

A related issue is the impact on tribal lands. Although technically owned by the federal government, tribal lands are held in trust for Indian tribes, which federal law recognizes as distinct, independent, political entities. The Tohono O’odham Nation, which has land on both sides of the border, has already pledged to fight the Trump administration on building a wall there. In 2007, the tribe agreed to allow the construction of a vehicle barrier on their land, but the Bush administration then waived laws that protect tribal burial grounds, and during construction, human remains were dug up. If the tribe refuses to cooperate, the Trump administration would need a stand-alone bill from Congress condemning the land.

Even on federal lands, it can take months to get various agencies to agree to allow Border Patrol to move forward on various projects. In 2010, two-thirds of patrol agents-in-charge told the Government Accountability Office that under land management laws, the interagency compliance process had delayed or limited access to portions of some federal lands. Some 54 percent said that they were unable to obtain responses to requests for permission to use the lands in a timely manner. In one case, it took nearly 8 months for Border Patrol to get permission to install a single underground sensor. Only 15 percent, however, said that these issues adversely impacted the overall security in their areas.

Practical Problems with Border Fences and Walls

Fences are difficult to maintain because they can be knocked down in storms and erode if they are near beaches or rivers that flood, as has happened in San Diego. Fences are also relatively easy to cut through, and Border Patrol repaired more than 4,000 breaches in one year alone. Low fencing can be easily mounted from the roof of a truck. Some fences can even be driven over with a ramp. All can be climbed or tunneled under. Watch this video of two American women climbing to the top of the 18-foot border fence in under 20 seconds. Border patrol spokesperson Mike Scioli calls the fence “a speed bump in the desert.”

Image 7: Vulnerabilities in a Border Fence or Wall

Source: Huffington Post

Tunnels are typically used more for drug smuggling, but they are still a serious vulnerability in any kind of physical barrier. From 2007 to 2010, Border Patrol found more than 1 tunnel every month. “For every tunnel we find, we feel they’re building another one somewhere,” a Border Patrol tunnel expert told the New York Times this year.

Trump’s wall could address some of these problems. A concrete wall, while not “impenetrable,” would probably significantly cut down on attempts at going through it, though it is clearly not impossible (see image above). He has also claimed that no one would ever use a ladder to go over a 50-foot wall because “there’s no way to get down,” before thinking about it for a second and conceding “maybe a rope.” Nonetheless, the height might discourage some migrants from climbing, and it would certainly take them longer to do so, which would give Border Patrol more time to reach them.

Trump has also attempted to say that no one could tunnel under his wall due to “tunnel technology,” but the Science and Technology Directorate has concluded that all current technology to detect tunnels beneath the border would not be “suited to Border Patrol agents’ operational needs.” As far as dealing with water, Border Patrol agents told Fox news that a border wall would still “have to allow water to pass through, or the sheer force of raging water could damage its integrity, not to mention the legal rights of both the U.S. and Mexico to seasonal rains.”

One major obvious downside to a wall is that it would be opaque. “A cinder block or rock wall, in the traditional sense, isn’t necessarily the most effective or desirable choice,” the agents told Fox news. “Seeing through a fence allows agents to anticipate and mobilize, prior to illegal immigrants actually climbing or cutting through the fence.” For this reason, the agency is desperate to replace the landing mat fences that are also nontransparent. Popular Mechanics called this part of the fence “obsolete, in need of replacement” because they “can be easy to foil since Border Patrol agents can’t see what’s going on the other side.”

At a basic level, a wall or fence can never stop illegal immigration because a wall or fence cannot apprehend anyone. The agents that Fox News spoke to called a wall “meaningless” without agents and technology to back it up. Mayor Michael Gomez of Douglas, Arizona labeled the fence a failure in 2010, saying “they jump right over it.”

Efficacy of Border Fences and Walls

The most important question in this debate is how much illegal immigration is reduced per each additional dollar spent on a wall compared to each additional dollar spent on more manpower or other technologies. Despite the importance of this question, apparently no estimate of the impact of the current border fence on illegal immigration exists at all, let alone a comparison to other technologies. This is despite more than a decade to conduct such a study for the recent fences, and even longer to study the earlier fences.

Rep. Henry Cuellar (D‑TX) attempted to obtain the answer to this exact question from the administration as a sitting congressman on the House Homeland Security Committee and failed. A Migration Policy Institute 2016 review of the impact of walls and fences around the world turned up no academic literature specifically on the deterrent effect of physical barriers and concluded somewhat vaguely that walls appear to be “relatively ineffective.” The closest thing I could find to a cost-benefit analysis of this type was from House Homeland Security Committee Chairman Michael McCaul, a Republican from Texas, who concluded after careful study in 2015 that “it would be an inefficient use of taxpayer money to complete the fence. … We are using that money to utilize other technology to create a secure border.” Rep. McCaul, however, did not detail the methodology underlying his conclusion.

Fences could have strong local effects. The case for more fencing often relies completely on these regional effects. The San Diego border sector is probably the most commonly cited success story in the debate over the fence. From 1990 to 1993, it replaced its “totally ineffective” fence with a taller sturdier landing mat fence along 14 miles of the border. This had little impact on the number of apprehensions. The Congressional Research Service concluded, “The primary fence, by itself, did not have a discernible impact on the influx of unauthorized aliens coming across the border in San Diego.”

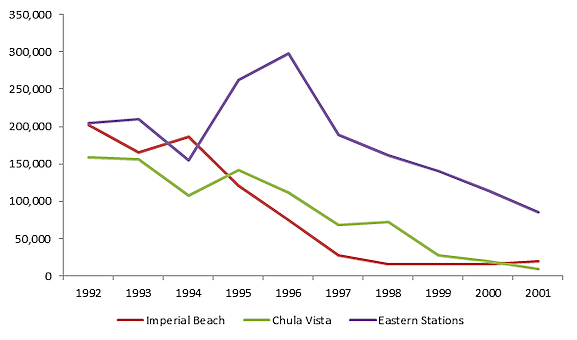

From 1994 to 1996, Operation Gatekeeper doubled the number of agents in the sector, but this too apparently had little effect on illegal immigration. Instead, as the image below shows, the flow dramatically moved eastward away from the Imperial Beach station and the Chula Vista station where fences were built and massively toward the other eastern stations.

Image 8: Apprehensions in San Diego Border Sector by Border Patrol Station

Source: CRS

Eventually the number of apprehensions in the San Diego sector crashed, indicating a huge shift in the flow of entries. But it is far from clear that this change actually reduced total entries. Indeed, the evidence indicates that walling off San Diego simply sent migrants looking for other means of entry further east—in the El Centro, Yuma, and Tucson sectors.

Image 9: Border Patrol Sectors in California and Arizona

Source: Tucson.com

From 1997 to 1999, Border Patrol installed 9 miles of secondary fencing in San Diego and extended the primary fence there. This period saw falling apprehensions in San Diego and rapidly expanding apprehensions in the adjacent sectors, almost equaling the previous flow.

Image 10: Apprehensions of Aliens at the Southwest Border by Sector in El Centro, San Diego, and Yuma

Source: Customs and Border Protection

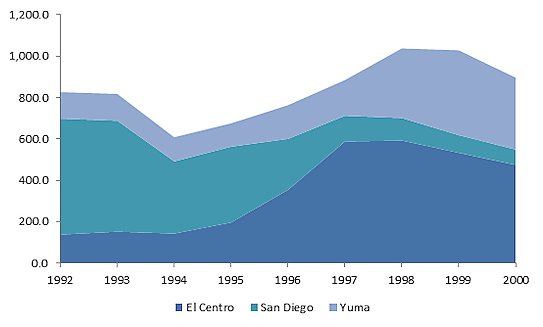

Of course, apprehensions could have increased in El Centro or decreased in San Diego due to less enforcement activity. Image 11 provides the number of apprehensions per border agent for each sector. But controlling for the number of agents changes the picture very little. In fact, it seems to indicate that the flow rose much more dramatically in Yuma and fell further in San Diego than the number of raw apprehension figures show. The total flow by this measurement actually rose overall in these areas, while the fences were built.

Image 11: Apprehensions Per Border Agent by Sector in El Centro, San Diego, and Yuma

Source: Customs and Border Protection (agents, apprehensions)

It would be ideal to perform the same type of analysis on the impact of the Secure Fence Act of 2006, but the problem is that the fences were rolled out at the same time as Congress doubled the size of the Border Patrol, jumping the numbers from 12,000 to 21,000. Moreover, fences went up on portions in many different sectors, so it is more difficult to isolate the effects. To complicate matters further, this period of time saw the collapse of the housing bubble, which caused a huge exodus of unauthorized workers back to Mexico even before the Great Recession hit.

This analysis reveals that Trump was likely correct to initially say that a wall only makes sense if it is truly across the entire border. But it also seems to indicate that the primary fencing alone had little impact on illegal immigration. Even the secondary fence needed to be reinforced with substantial increases in the number of border agents. It also does little to answer the question of whether a fence is worth its cost relative to other uses.

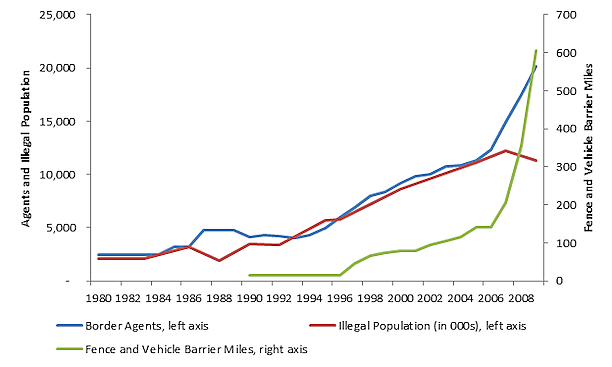

Douglas Massey, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania, argues that the true measure of efficacy should be not the flow into the United States, but also the flow out of the country. He notes that until the fences and agents were deployed in the 1990s, unauthorized immigrants typically returned home at the end of the harvest, leaving the total illegal population almost the same during the 1980s (image below). But as the costs and risks of doing so increased, they tried almost as hard to enter, while barely any tried to leave. The border security efforts essentially trapped them in and made the problem worse.

Image 12: Unauthorized Immigrant Population and Number of Border Patrol Agents (1980–2009)

Sources: Warren and Passel (1980); Census Bureau (14 and up only, 1983); Congressional Research Service (1986–1988); Pew Research Center (1990–2009); Border Patrol; CRS (fencing)

As the image above shows, the illegal population continued to rise in parallel with the growth in agents until the housing bubble burst in 2007. Growth in the fence length is also correlated to a lesser extent with increases in the illegal population over this period. Massey estimates that 5.3 million fewer people would be here illegally had enforcement not been changed and argues that a large guest worker program that mimicked the earlier illegal traffic would eliminate illegal immigration as well as lower the total immigrant population in the United States. Donald Trump has repeatedly promised doors in his wall to expedite legal immigration into the United States, so it is possible that he could follow through on this proposal, but his more specific positions on legal immigration have been targeted to decrease legal admissions, not increase them.

Financial Costs of the Border Fences

There appears to be no official estimate for the entire cost of the current fence from 1986 to today. Congress initially expected to spend $1.2 billion on the project, but actually spent $2.4 billion on just the fences—including vehicle barriers—constructed between 2006 and 2009 with another $1.1 billion appropriated ($3.5 billion total).

In 2009, Customs and Border Protection predicted that it would need another $6.5 billion over 20 years to maintain just that fencing. The Washington Post reported in 2015 that the Congressional Research Service found that this fencing had already cost $7 billion, which implies the maintenance costs were far higher than predicted. The Obama administration requested $274 million to maintain the fences in 2015—nearly $1 million per mile of pedestrian fencing. Assuming costs escalate over time, that’s close to $3 billion per decade.

If we simply divide $3.5 billion by 617 miles of fence, we get an estimate of $5.4 million per mile. Using the $7 billion figure, then each mile cost $10.9 million. We simply cannot project these costs into the future because the first fences built were in urban, flat areas that were easily accessible, so costs were lower. The General Accountability Office found that the average mile of fence for the first 70 miles cost $2.8 million. For the next 225, the average cost rose to $5 million per mile. The GAO assumed the average cost per mile for the next 26 miles would be $6.5 million. Some particular areas were astronomically high—$16 million per mile in the mountainous region east of San Diego.

Sticking with the low $6.5 million per mile number, we get some $4.4 billion to build out the existing fence to 1,000 miles—upfront cost, ignoring all later maintenance costs. We could expect another $5.4 billion for a 10-year estimate of about $10 billion. But it is almost definitely higher than this due to the costs associated with acquiring private land and building in less accessible areas. The entire 1,000 fence would have cost the government at least $18 billion (accounting for inflation) to finish. It is also important to remember that this is for a single layer of fence. A second layer, which is what many people advocate, would almost double the cost. If Trump wanted to upgrade the existing “joke” fencing and build it out to a full 1,000 miles, then it would be much higher than that.

Financial Cost of Trump’s Border Wall

Trump has insisted that his wall will not be a fence, but rather an “impenetrable physical wall,” and has also claimed that it would cost between $10 and $12 billion without revealing his methodology. But since building out the existing fence would cost more than that, his wall will undoubtedly cost even more.

Moreover, the fences were relatively inexpensive to build because they were constructed from, for example, old metal from helicopter landing pads from Vietnam or built low to the ground in certain areas. Trump has criticized the current fences on several grounds, including but not limited to their inability to prevent tunneling, their materials, their height, and their aesthetics. Trump’s wall would use, according to one engineer’s estimate, more than 1.5 times as much concrete as the Hoover Dam.

For the full 1,000 miles, Trump’s 30-foot wall (with a 10-foot tunnel barrier) would cost $31.2 billion, according to the best estimate from Massachusetts Institute of Technology engineers—that is $31.2 million per mile. If he only built 500 miles, the cost would be a more manageable, but still shocking $15.1 billion. Two other estimates placed the construction cost of the wall in the $25 billion range. Again, these are upfront construction costs, not ongoing maintenance costs, which account for roughly half of all of the fence costs over a decade.

Payment for the Wall

Donald Trump has been most insistent that Mexico will pay for the wall. He has promised a variety of ways of accomplishing this. The idea he raises most often is that Mexico can pay for the wall because it sells so much to U.S. consumers. “The wall is a fraction of the kind of money… that Mexico takes in from the United States,” he told CNN in April. “You’re talking about a trade deficit with Mexico of $58 billion.” In other words, if the Mexican government does not pay the $25 billion or more that it will take to build the wall, Trump will simply tax business with Mexico.

Of course, under this scheme, it is simply inaccurate to claim that “Mexico” will be paying for the wall since the $58 billion comes from U.S. consumers. If the United States imposes a tax on Mexican imports, then U.S. consumers will cover it. Marco Rubio told this to Trump during one of the presidential debates in January, explaining that the government “doesn’t pay the tariff—the buyer pays the tariff.” But obviously the lesson in economics failed to stick.

Trump has also proposed cutting off remittances of unauthorized immigrants to Mexico if the Mexican government refuses to cover the cost of the wall. Trump’s proposed regulatory method of doing this (claiming that cash wire transfers are actually bank accounts) is legally suspect, but even if it was legal, it would not cover the cost of the wall. Although Mexican immigrants remit $26 billion to their families in Mexico, this plan is fundamentally flawed for several reasons.

First of all, this amount is not enough to cover the cost of the wall. Second, only half of the Mexican immigrants in the United States are here illegally. Third, the majority of the remittances from unauthorized immigrants would find a way home through means other than wire transfers. Fourth, the Mexican government has no control over the remittances, so it cannot hand them over to the Trump administration. Fifth, Mexico does not want a wall, so they may be willing to take an economic hit to not have a wall.

These realities might already be occurring to Trump’s staff. Trump advisor Kris Kobach said after the election, “There’s no question the wall is going to get built. The only question is how quickly will it get done and who pays for it?” Kobach, who is part of the president-elect’s transition team, promised to find ways to begin work on the wall immediately using the existing budget.