A study

that examined the effects body worn cameras (BWCs) have on police officers in Washington, D.C. has been making the rounds recently. The study’s findings have reinvigorated discussions about BWCs, not least because of its counterintuitive finding that BWCs did not have a statistically significant effect on officers’ use of force or civilian complaints against the police. This finding is worth considering, but the study shouldn’t deter local officials from mandating police BWCs. Even if they don’t change police officers’ behavior, BWCs can, with the right policies in place, provide a much-needed increase in police accountability and transparency.

During the study, officers with the Metropolitan Police Department of the District of Columbia were randomly assigned BWCs. Researchers with The Lab @DC, a study team in the D.C. mayor’s office, and Yale University examined use of force incidents and complaints against police officers.

The study did not seek to measure the impact of BWCs’ other benefits such as accountability, transparency, and protection for officers, but rather narrowly measured their impact. In addition to examining how often police officers use force and are the subject of complaints, researchers also studied police discretion and the judicial outcomes related to police charges.

You might expect that officers improved their behavior when they were wearing BWCs. After all, if you know that you’re being filmed you have plenty of incentives to be on your best behavior, whether you’re an officer or a resident. And yet, the recent D.C. body camera study showed that BWCs had no statistically significant effect on officers’ behavior.

This may strike many as odd. But we shouldn’t forget the limitations that restrict researchers looking into the effects of BWCs. Researchers cannot, for instance, insist that when an officer wearing a BWC calls for backup that only officers also wearing BWCs respond. In a situation where two officers are interacting with a resident and only one of the officers is wearing a BWC there is a good chance that the BWC will influence the behavior of the officer not wearing the BWC.

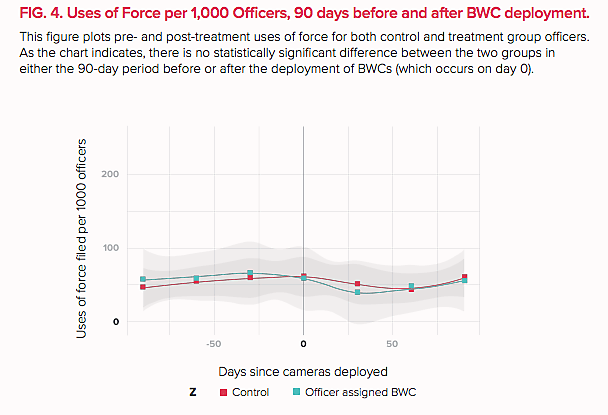

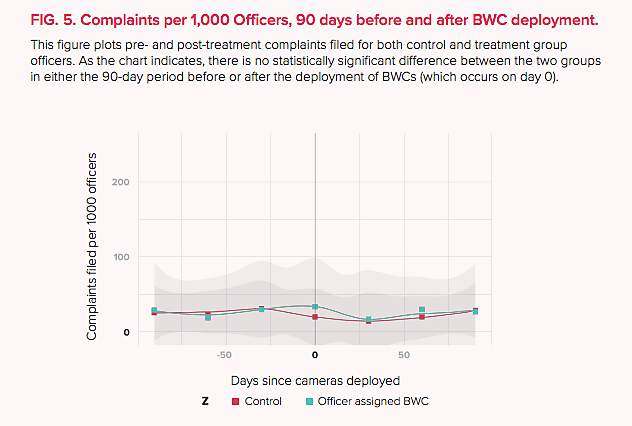

The researchers do not think, however, that this spillover effect affected the results of the experiment. The study notes that there was no statistically significant difference between officer behavior pre- and post-BWC deployment, as the two graphs from the study below show:

If officers not wearing BWCs improved their behavior in the presence of other officers wearing BWCs, we’d expect to see a reduction in use of force and complaints filed after the study began. However, Figure 4 and Figure 5 above show no significant difference.

Thus, even given the limitations of the study design, it appears that BWCs do not at a mass scale reduce the amount of force police officers use or the number of complaints officers receive.

The Washington, D.C. study raises an obvious question: if BWCs have no statistically significant effect on officers’ use of force or complaints, should officers be wearing them?

The answer to that question is “yes.”

First, even if body cameras do not reduce the frequency with which police officers use force, they nonetheless help provide accountability for the minority of officers who engage in serious misconduct, such as the Baltimore police officers caught planting drugs and “re-creating” a crime scene.

Second, BWCs are a tool for increased transparency in American law enforcement. Residents deserve to know how police officers behave, whether their behavior is changed by BWCs or not. At a time when cell phones are ubiquitous and BWCs are a regular feature of police misconduct debates, residents will be increasingly skeptical when a contentious fatal police encounter is not filmed. Even if a bird’s eye view of a police department reveals that BWCs don’t have a statistically significantly effect on police officers’ use of force, that doesn’t mean that same department won’t one day hire a bad police officer who will engage in illegal and deadly misconduct.

Third, BWCs can also protect police officers by minimizing time spent on baseless complaints against officers by providing clear exculpatory evidence, as was the case when a young woman falsely accused an Albuquerque Police Department officer of sexual assault during a 2014 DWI stop.

All of these BWCs benefits can only be realized with the appropriate policies in place. Without policies that protect privacy and allow residents to view body camera footage of public interest, body cameras could be used as a surveillance tool.

The authors of the Washington, D.C. study state that their results “suggest that we should recalibrate our expectations of BWCs’ ability to induce large-scale behavioral changes in policing.” But even if BWCs don’t prompt significant changes in police officers’ behavior they are worth mandating anyway. A police department with BWCs governed by the right policies will increase transparency and accountability—a welcome result even if it’s not accompanied by better-behaved police officers.