There’s an old joke about a drunk looking for his keys under a lamp post. A police officer comes along and helps with the search for a while, then asks if it’s certain that the keys were lost in that area.

“Oh no,” the drunk says. “I lost them on the other side of the road.”

“Why are we looking here?!”

“Because the light is better!”

In a way, the joke captures the situation with public oversight of politics and public policy. The field overall is poorly illuminated, but the best light shines on campaign finance. There’s more data there, so we hear a lot about how legislators get into office. We don’t keep especially close tabs on what elected officials do once they’re in office, even though that’s what matters most.

(That’s my opinion, anyway, animated by the vision of an informed populace keeping tabs on legislation and government spending as closely as they track, y’know, baseball, the stock market, and the weather.)

Our Deepbills project just might help improve things. As I announced in late August, we recently achieved the milestone of marking up every version of every bill in the 113th Congress with semantically rich XML. That means that computers can automatically discover references in federal legislation to existing laws in every citation format, to agencies and bureaus, and to budget authorities (both authorizations of appropriations and appropriations).

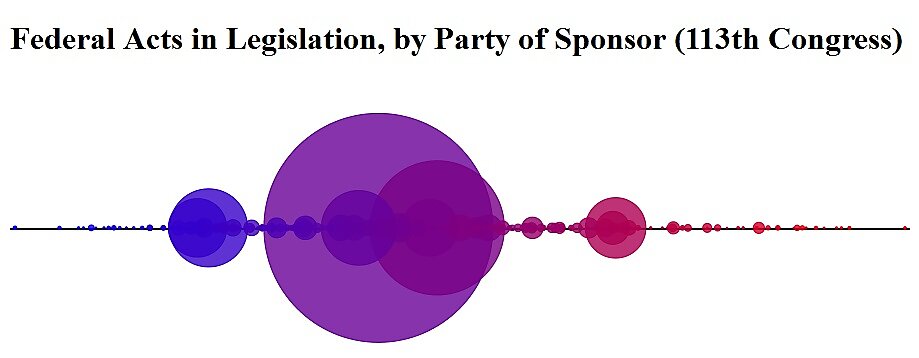

Machine‐readable bills can tell stories that we hadn’t heard before, and Deepbills has interesting information about the 113th Congress. The image above is of a visualization showing partisan interest in existing laws during the 113th Congress.

What laws were Republican members of Congress trying to amend the most in 2013 and 2014? What about Democrats? The visualization has your answers. Click to see it. As far as I know, it’s the first time this information has been available.

Yes, your expectation of a Republican fixation on Obamacare is generally confirmed (as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act). And you won’t be surprised to see Democratic interest in the Family and Medical Leave Act. Democrats legislate more than Republicans; that jibes with expectations.

The new information here, for many people, is the relative numerosity and bipartisan interest in amendments to the Internal Revenue Code and Social Security Act. These two laws are vastly more important to Congress than pretty much anything else, by this imperfect metric.

Is the public spending its time focused on partisan issues, not realizing where their representatives are spending their time? Knowing this may change the behavior of all actors.

This data is hard to produce, and I live in fear of gross errors in the data or the creation of the visualization. Happily, a more authoritative source—Congress—has committed itself to providing data like this in the future. They’ll do a much better job originating bills as data than we could possibly do with post‐processing. Early this year, aware of our work, the House amended its rules, asking the Committee on House Administration, the House Clerk, and others to “broaden the availability of legislative documents in machine readable formats.”

I look forward to better data giving political scientists more skillful than me the chance to formulate and test theses about congressional behavior. It will be especially interesting when we have time series data so we can see if it’s really true that senators get magically interested in home‐state issues during the year‐and‐a‐half before election time. And—oh yeah—won’t it be neat when the public can oversee Congress directly and clearly through hundreds of web sites, information services, and apps? Yes, it will.

Thanks go to Sam Corcos for producing this visualization, and to the Democracy Fund for supporting the Deepbills work that made it possible.