Global Science Report is a weekly feature from the Center for the Study of Science, where we highlight one or two important new items in the scientific literature or the popular media. For broader and more technical perspectives, consult our monthly “Current Wisdom.”

Many eyes will be on President Obama’s State of the Union address tonight watching to see how he follows his inauguration promise to “respond to the threat of climate change.” Rumors are flying that he will use his executive power to bypass Congress and further EPA efforts to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. But his best response would be to get the federal government out of the energy market and allow it to flourish as it may. The inconvenient truth is that the U.S. influence on global climate is rapidly diminishing as greenhouse gas emissions from the rest of the world rapidly expand. As a consequence, whether or not the United States reduces its emissions at all is immaterial to the path of future climate change and its impacts.

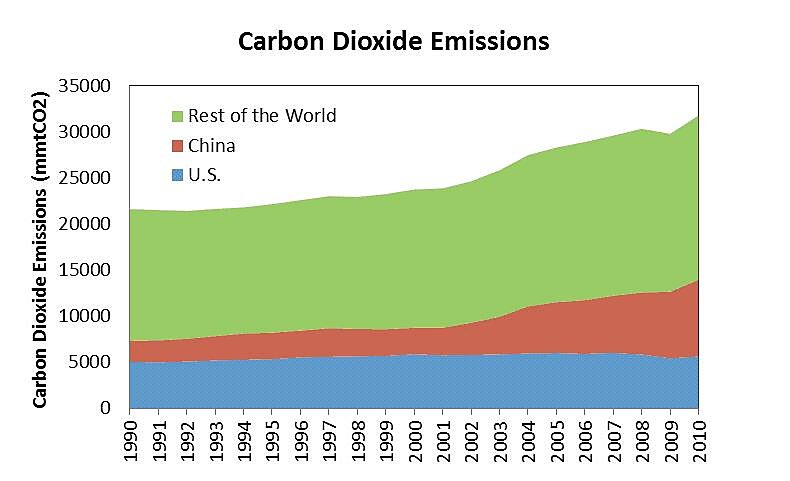

Several reports last week have shown that carbon dioxide emissions from the United States declined in 2012 and now stand at a level on par with what they were back in 1994. U.S. carbon dioxide emissions have dropped about 13 percent from their high in 2007.

All the while, global carbon dioxide emissions have been on the rise—primarily fueled by rapid emissions growth in developing countries, namely China (which is responsible for about two-thirds of the global increase during the past decade).

[caption align=“center”]

Figure 1. Emissions of carbon dioxide from the U.S., China, and the rest of the world, 1990–2010 (data from U.S. Energy Informat[/caption]

Since carbon dioxide is well-mixed in the atmosphere, who actually emits it is of little consequence when it comes to its potential to lead to global warming. This means that the global percentage of a country’s annual carbon dioxide emissions is equivalent to its annual percentage contribution to the increased warming pressure (we use the term “warming pressure” to indicate that things other than the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases also act to influence that global average temperature from one year to the next). Since total global carbon dioxide emissions are quickly distancing themselves from U.S. emissions, as time passes, the relative influence of U.S. emissions on the future state of the global climate is rapidly declining.

We recently showed that the United States will be responsible for only about two-tenths of a degree Celsius of total global warming by the end of this century, or about 7 percent of the total projected warming—an amount hardly worth worrying about. The rest of the world will be responsible for the other 93 percent.

So when the president promises to “respond to the threat of climate change,” domestic actions will have virtually no impact—and yet those are the ones that are being put on the table with proposals like cap and trade, carbon taxes, emissions limits on new power plants, and actions like fuel economy standards, renewable energy subsidies, ethanol requirements, etc. (We purposely left Keystone XL pipeline off this list because it will have no significant effect on U.S carbon emissions).

What the president really hopes to achieve by trying to force down U.S. emissions is not direct climate change mitigation, but one or more of the following: to gain some bargaining power at international talks to address climate change; that other countries will follow the United States’ lead; or that new, lower emitting energy technologies will be developed and rapidly and safely deployed around the world.

There is no guarantee of these outcomes. For instance, developing countries may find it to be more in their interest to energize their economies and their citizenry through low cost and proven methods (i.e., fossil fuels) than submit to a we’ve-got-ours-but-now-you-can’t‑have-yours dictate. Or new, low-emitting energy technologies may be developed without the extra incentives.

But in any case, the United States receives no direct climate benefits until, or unless, the rest of the world makes sizeable greenhouse gas emissions reductions.

It seems rather bizarre that our own president would support actions aimed at holding Americans hostage to limited energy choices (and quite probably higher energy prices) while hoping that the rest of the world will come to our rescue in the form of reducing carbon dioxide emissions such that future global climate change is reduced to a degree as to result in a significant and detectable mitigation of weather/climate impacts in the United States.

Rather than this wait and hope attitude, the president ought to take steps to encourage actions that would enable us to better fend for ourselves no matter what happens— actions aimed towards expanding our energy resources, growing our wealth and improving our resilience to what lies ahead. This path is paved with less government interference, not more.