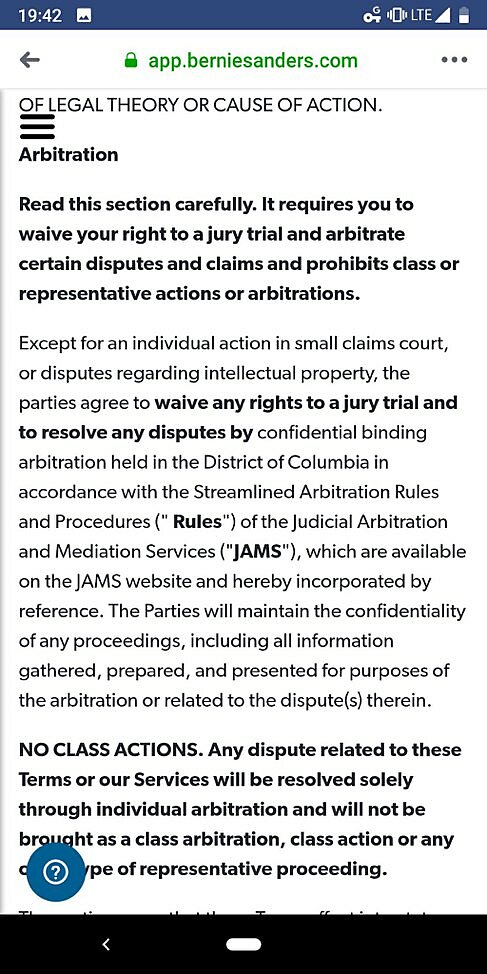

“Read this section carefully. It requires you to waive your right to a jury trial and arbitrate certain disputes and claims and prohibits class and representative actions or arbitrations.” — from the “Bernie App.” (illustration via @NC_CyberLaw on Twitter).

That’s right. The campaign-ready “Bernie app” released this week requires its users to agree to submit to arbitration in case of dispute, in place of lawsuits and especially class actions. As Ted Frank observes, “Even Bernie Sanders recognizes the importance and value of arbitration in navigating a legal system designed to benefit lawyers over the interests of consumers and businesses.”

The thing is, the Vermont senator has been railing for years against this sort of contractually-provided-for arbitration. A year ago he denounced the Supreme Court’s Epic Systems decision, which allowed employers to do what his app does and use arbitration language to fend off possible class actions. Just two weeks ago the former Burlington mayor said he was introducing a bill to outlaw contractually specified arbitration for many workplace disputes. As in the case of the flap over how the inveigher against millionaires has made good money as a book author, wouldn’t it be nice if he began preaching what he practices?

Sanders is hardly the only one for whom a gap can be observed on this matter between words and deeds. Take the New York Times, which has heatedly editorialized against arbitration clauses in the context of credit cards and insurance contracts while using them itself. Or the lawyers who took a challenge to cellphone-contract arbitration to the Supreme Court in AT&T v. Concepcion — what’s in the contract they offer their own clients? You guessed it.

When arranging their own dealings with clients, customers, and even campaign supporters, all these actors recognize that arbitration offers many advantages over no-holds-barred litigation and especially over class actions and similar devices, under which ambitious lawyers can step in and manage the grievance process for their own benefit while magnifying stakes through mechanical damages multiplication.

In last week’s decision in Lamps Plus v. Varela, the Supreme Court ruled that courts should not read class grievance mechanisms into arbitration agreements that are silent or ambiguous on the subject. Like many in the Court’s seemingly endless string of cases on arbitration, mostly arising from statutory interpretation rather than constitutional law, it was decided by a 5–4 split along liberal-conservative lines.

In Lamps Plus, the long-term stakes were less than usual for this line of cases. Why? Because had the Court adopted the liberal Justices’ view, the practical effect would have been to set off a rush to insert language into all existing agreements so as to make the exclusion of class relief explicit and unambiguous, exactly as the Bernie app does. When the dust settled, the actual distribution of rights between the two contracting sides would have reverted to where it started, while lawyers would have made a ton of money both drafting the new language and litigating the stray cases where the language did not change fast enough. But at least there would have been a chance for some hand-waving about helping out the little guy.