On May 21, 2014, Leszek Balcerowicz will receive the 2014 Milton Friedman Prize for Advancing Liberty during a dinner at the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York. The prestigious annual award by the Cato Institute carries with it a well-deserved check for $250,000.

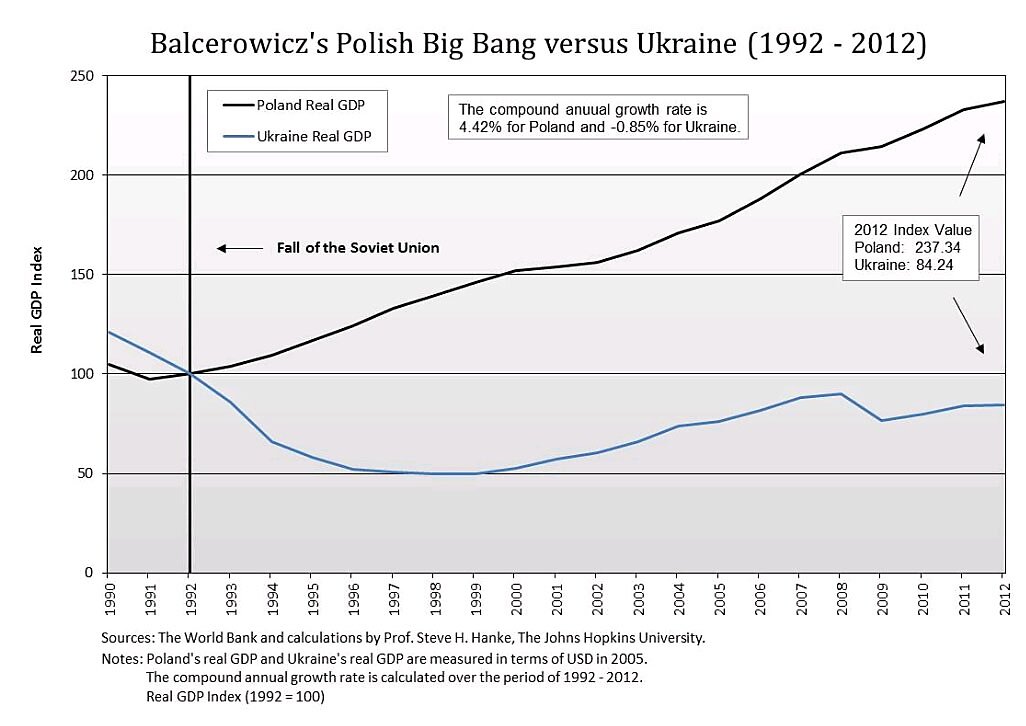

For those who might have forgotten the accomplishments of my long-time friend, allow me to suggest that, in Balcerowicz’s case, a picture is literally worth a thousand words.

But, before the picture, a little background.

In 1989, Balcerowicz became Poland’s Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister in Eastern Europe’s first non-communist government since World War II. Balcerowicz held these positions from 1989 through 1991, and again from 1997 through 2000. Subsequently, in 2001, he became the Chairman of the National Bank of Poland, a post he held until January 2007.

A student of the “Five P’s”: prior preparation prevents poor performance; Balcerowicz was ready when he first took office in 1989. Indeed, he pulled his comprehensive economic game plan to liberalize and transform the Polish economy out of his desk drawer and proceeded to implement what became known as the “Big Bang”. As they say, the rest is history.

The results of the “Big Bang” speak for themselves in the accompanying chart. Poland’s economy has more than doubled since the fall of the Soviet Union in 1992, growing at an average annual rate of 4.42%.

What about neighboring Ukraine? The contrast with Balcerowicz’s Poland couldn’t be starker. As Oleh Havrylyshyn, the former deputy finance minister of Ukraine, spells out in his classic book – Divergent Paths in Post-Communist Transformation: Capitalism for All or Capitalism for the Few – Ukraine rejected the Big Bang, free-market approach to reform. In consequence, it has taken a road to nowhere, remaining in the shadow of a corrupt communist system.

Unlike Poland’s prosperity, Ukraine has witnessed a post-Soviet contraction in its economy. Yes, the Ukrainian economy has been contracting at a real annual rate of almost 1% since the fall of the Soviet Union. Accordingly, it is smaller today in real terms than it was in 1992.

Many think the International Monetary Fund, which just ponied up $17 billion for Ukraine, will turn things around. Don’t hold your breath. Over the years, the IMF has dispensed its medicine and money in Ukraine with negative results.

When it comes to much-needed liberal economic reforms, one has to do something big; something that captures the public’s imagination and garners wide support. Unfortunately, Ukraine lacks a clear economic game plan – one with wide popular support.