The Jones Act has been a blight upon the United States for nearly 100 years. That the law survives despite its well-documented costs can in large part be ascribed to frequently made claims that it is vital to U.S. national security.

Such claims should be greeted with a skeptical eye.

As I explain in a new paper, decades of evidence suggest any contributions made by the law to national security are vastly overstated. In fact, there is considerable reason to think the Jones Act is a net national security liability.

The facts are these: under the Jones Act’s watch the U.S. maritime sector has suffered grievous setbacks. Numerous shipyards have closed, the domestic fleet’s numbers have dwindled, and the pool of mariners that the military draws upon to crew its sealift fleet has become perilously shallow. Rather than ensuring, as the law states in its purpose, a “merchant marine of the best equipped and most suitable types of vessels” capable of “serv[ing] as a naval or military auxiliary in time of war or national emergency” the Jones Act has produced a depleted, decrepit fleet of limited capabilities.

The Jones Act is complicit in this decline. The law, after all, is rooted in an absurd logic: that to promote both a strong U.S. shipbuilding sector and domestic fleet the latter must be compelled to purchase from the former. The result is the achievement of neither, which is the predictable outcome of linking two protected, uncompetitive sectors together.

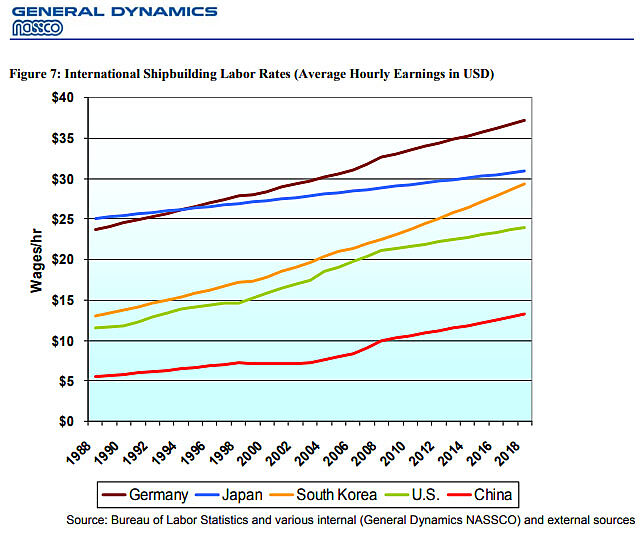

U.S. commercial shipyards, oriented towards the captive Jones Act market, lack the scale and specialization that can only be achieved by building for the international shipbuilding market. As a result, the limited number of ships they produce are up to five times more expensive than those built abroad. It is a testament to their technological inferiority and lack of productivity—hallmarks of protected markets—that they do so while offering wages that are lower than those of most leading shipbuilding countries.

Jones Act carriers that operate these wildly expensive ships, meanwhile, are forced to pass their acquisition costs along to consumers in the form of higher shipping rates. This, in turn, means less demand for their services, and thus fewer ships and mariners. Where consumers have a choice, they almost invariably opt for other forms of transportation such as trucks, railroads, and pipelines. Indeed, the 99 ship Jones Act fleet almost exclusively operates where there is low elasticity of demand and little competition, serving the shipping-dependent noncontiguous states and territories and the needs of the world’s largest oil-producing country (tanker ships account for 57 of the fleet’s 99 ships and roughly 80 percent of its deadweight tonnage).

Conceived in protectionist fallacies, the case for maintaining the 1920 Jones Act becomes ever more tortured given its increasingly glaring divorce from modern maritime realities. Among these:

- The sharp rise in cost differences between U.S. and foreign-built ships. Shortly after the Jones Act was passed a U.S.-built ship was typically about 20 percent more expensive than one built abroad. That cost difference can now reach 400 percent.

- The increased specialization of commercial ships. The military places a premium on flexible vessels that can operate in a variety of port environments and carry different types of cargo, while the commercial sector prizes ships geared towards specific tasks that disperse their cargo in modern ports. This makes the ships of the Jones Act fleet less valuable to the military.

- The heavy reliance of U.S.-built Jones Act ships on foreign capital, components, and know-how. Jones Act ships almost invariably use foreign designs and are heavily dependent on foreign sources for critical components such as the engine and propeller. Furthermore, the shipyards themselves are often the subsidiaries of foreign parent corporations. Any notion that the high price of Jones Act ships has produced a U.S. shipbuilding capability free of foreign dependence is entirely illusory.

A new approach is needed.

Rather than maintain the Jones Act status quo with its opaque costs and inequitable burdens that are disproportionately placed upon Alaska, Hawaii, and Puerto Rico, the United States should consider some of the following measures to meet the U.S. military’s need for ships and mariners to transport supplies and equipment:

- The establishment of a civilian Merchant Marine Reserve. The military currently lacks needed certainty around the availability of manpower to crew its sealift vessels in wartime. U.S. merchant mariners, meanwhile, are not provided with the training and benefits commensurate with their role in assuring U.S. national security. A civilian Merchant Marine Reserve could help address this.

- Wage subsidies to the employers of U.S. mariners. To make the employment of U.S. mariners more attractive, the United States could offer wage subsidies to those who employ them in exchange for an agreement that they be released for wartime service with guaranteed employment upon their return.

- Allowing the use of foreign mariners in some circumstances. To ease crew shortages the United States should consider the use of foreign mariners in some circumstances. To help mitigate possible risks measures such as background checks and eligibility restrictions to citizens of certain countries could be implemented.

To learn more please read the paper in its entirety here and visit Cato’s dedicated Jones Act webpage.