“How Coronavirus Cases Have Risen Since States Reopened” in The New York Times July 9 claimed, “Florida and South Carolina were among the first to open up and are now among the states leading the current surge. In contrast, the states that bore the brunt of cases in March and April but were slower to reopen have seen significant decreases in reported cases since. Average daily cases in New York are down 52 percent since it reopened in late May and down 83 percent in Massachusetts” (which reopened May 18).

The purpose of this note is to question whether or not it is accurate to simply attribute the “current surge” in cases or deaths to the “states first to open up.”

The New York Times article showed the percentage changes in cases since reopening – the date when states “lifted order to stay at home or allowed major sectors such as retail, restaurants and personal care services to reopen either statewide or in most areas.” Eight states “first to open up” reopened before May 1, twenty more before May 15, and twenty-two states were “slower to reopen” from May 15 to May 29.

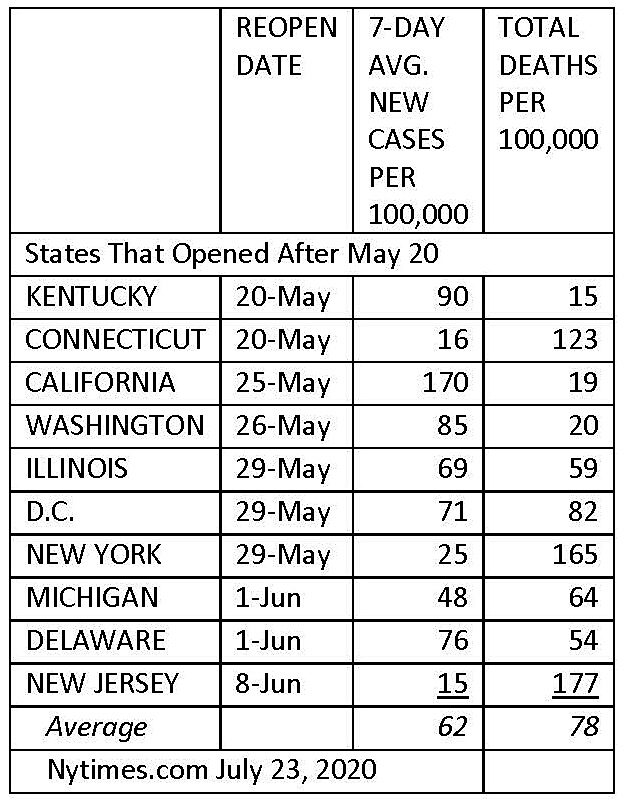

Unfortunately, the author’s main example – saying Florida was “among the first to open up” on May 4–puts that state into his middle group (May 2 to May 14). To keep 70% of Florida in the narrative (Southeast Florida remained closed), my Table defines early reopening as May 4 or earlier. I redefine late reopening to mean ten states (including D.C.) that reopened after May 20, because the author’s May 15 definition of late is not much later than May 4. Reopening dates are from the New York Times article. Statistics on new cases per day from a recent 7 day average and on total deaths per 100,000 residents from the beginning were in nytimes.com on July 23.

About a third of the 23 states that opened by May 4 (four with Democrat Governors) did see relatively high daily numbers of new cases over the 7 days ending July 22, famously including Texas and Florida but not Arizona (which reopened May 8). About 15 of the early-reopening states have not seen a significant “surge” of new cases. California had such a surge, but was one of the last states to reopen.

What all of the early reopening states have in common is not how many positive cases they’ve had tested in the past two weeks, but how few deaths they have had since the virus began. Unusually low death rates in all 23 states explain why so many reopened early. Conversely, very high death rates in states with densely-populated cities explains why they reopened late – such as the NY/NJ/CT corridor, Chicago, Detroit and Washington D.C.

On July 17 another New York Times article, “After the Surge in Coronavirus Cases, Deaths Are Now Rising Too,” claimed daily deaths per million in 18 states over a 7‑day span were higher than on June 1. Any detected rise in a state’s daily deaths, however small, was again blamed on “the reopening and relaxing of social distancing restrictions in some states.” But that is not what that article’s statistics showed.

Increases in daily deaths were expressed as percentage changes, not numbers. Oklahoma deaths were up by less than one person per million, yet that was labeled a 19% increase. A map highlighting 20 “States where deaths have increased [in percentage terms] since June 1” includes Hawaii with only 24 deaths since the virus began, and Alaska with only 17. Aside from Alaska and Hawaii, only 18 other states had any rising deaths, which means most states had falling deaths. Contrary to the “early reopening” theme, eight states with falling deaths were among the earliest reopening states – Georgia, Mississippi, Missouri, Nebraska, Iowa, Maine, Indiana and Colorado. The last five early-opening states saw COVID-19 deaths fall by 60–70% since June 1, according to the same article.

Without careful cherry-picking among the 23 states that opened early, the date of reopening can’t explain which states have recently experienced rising cases, much less rising deaths. California proves that reopening late does not by itself protect a state from a surge in new cases. Yet California is a rare state that reopened late despite few deaths (Washington may look like another, but Seattle had the first big nursing home crisis).

On the other hand, differences in death rates almost always explain which states opened early or late. Those with relatively few deaths (16 per 100,000 in Texas compared with 123 in Connecticut) have experienced almost flat epidemic curves – that is, cases and deaths did not rise sharply and then fall but instead remained low and little changed until recently.

By contrast, having suffered unusually high numbers of infections and deaths by April as late-openers did reduces today’s odds of another big bout of community spread. Former super-hot spots like the NY-NJ-CT Metropolitan area have now acquired sizable pockets of COVID-19 resistance (“immunity”) with previously-infected people now acting as a buffer to reduce contagion risk for their neighbors.