There appears to be a frenzy of book “banning” in public schools, with the challenge to Maus in a Tennessee district just the most recent to grab headlines. But has there truly been an explosion of challenges? And if so, why?

Cato’s Center for Educational Freedom has tracked conflicts over reading material – books either stocked in school libraries or prescribed in classes – since the 2005-06 school year, along with many other types of values- and identity-based conflicts in public schools. They are part of the data collection behind the Public Schooling Battle Map, through which the public can access information on such battles by state, school district, year, and more.

The conflicts have been collected through daily reading of education news, captured by Google alerts for subjects such as “banned books” and by news aggregators such as the ChoiceMedia.tv “Newswire.” The collection is not exhaustive – there are likely many conflicts that do not get reported by media, or that generate reports we do not see. We also only began fully regularized collection around 2012. Still, the multi-year timeframe can likely provide some insights into trends.

Is It an Explosion?

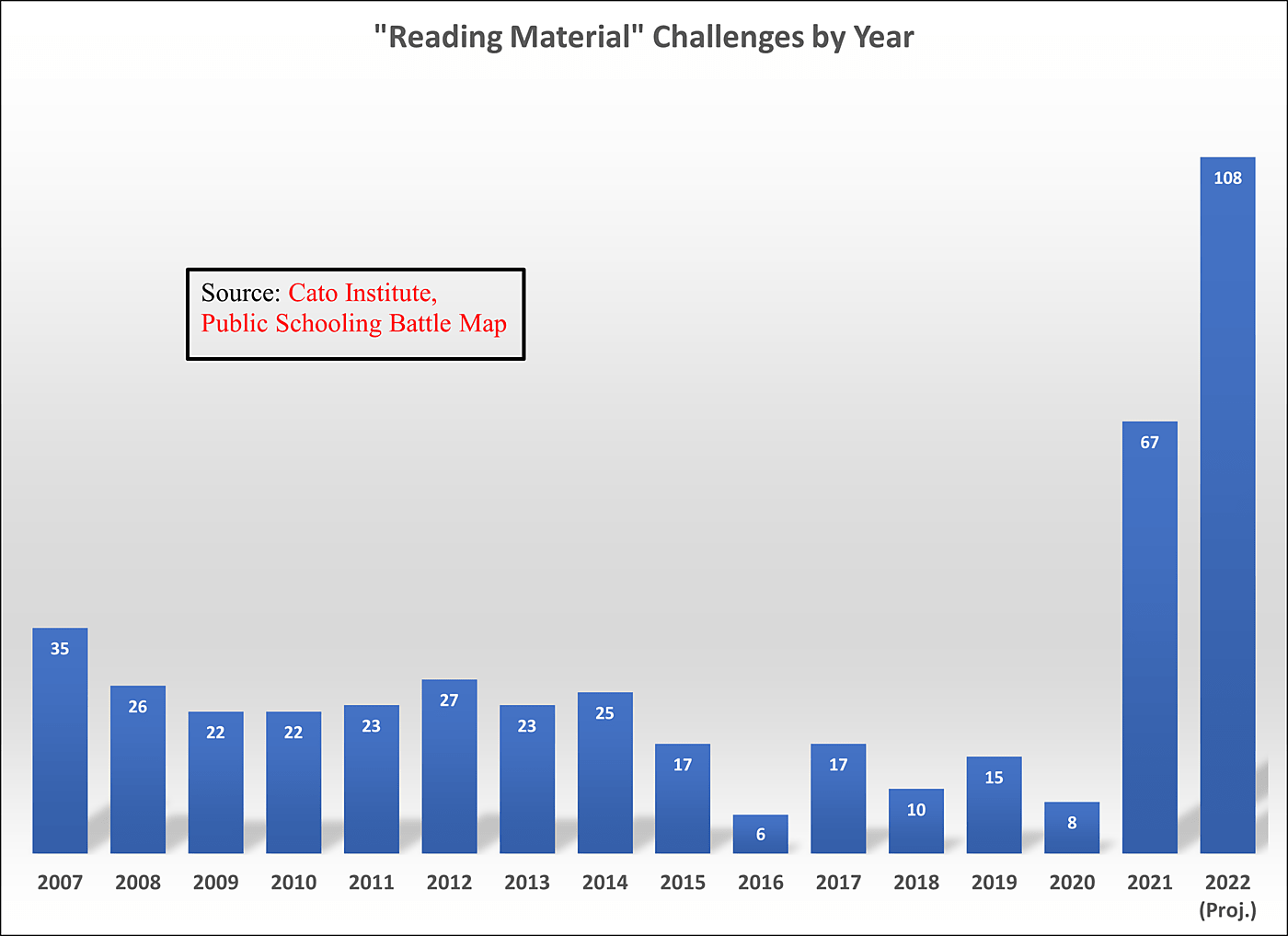

The chart below shows the number of “reading material” battles we have catalogued since 2007, the previous high. In 2021, we recorded 67 battles, almost a doubling of 2007. As of roughly the end of January we had recorded nine reading material fights in 2022, which projects to approximately 108 battles for the current year. Of course, the year is early, but combined with the late-2021 numbers we do seem to be in the midst of a challenged-books boom.

Importantly, there are about 13,500 school districts in the United States, so our collection includes a very small share of all districts. On the flip side, some battles are at the state level, including the legislative effort in Texas to investigate 850 titles, which pushes every state resident into the book brouhaha. And many districts are quite small, likely not generating easily discovered media reports.

What Lit the Match?

We have been seeing significant unrest in education regardless of book battles, sparked most broadly by frustration with schools’ responses to COVID-19, including closure and masking decisions. Also, at least some share of Americans have been very angry about school district “equity” pushes, often subsumed under “critical race theory.” These pushes appear to have ballooned after the May 2020 police murder of George Floyd, but a heated national debate about how we understand and teach race in the United States was already underway after the August 2019 publication of the New York Times’ “1619 Project.”

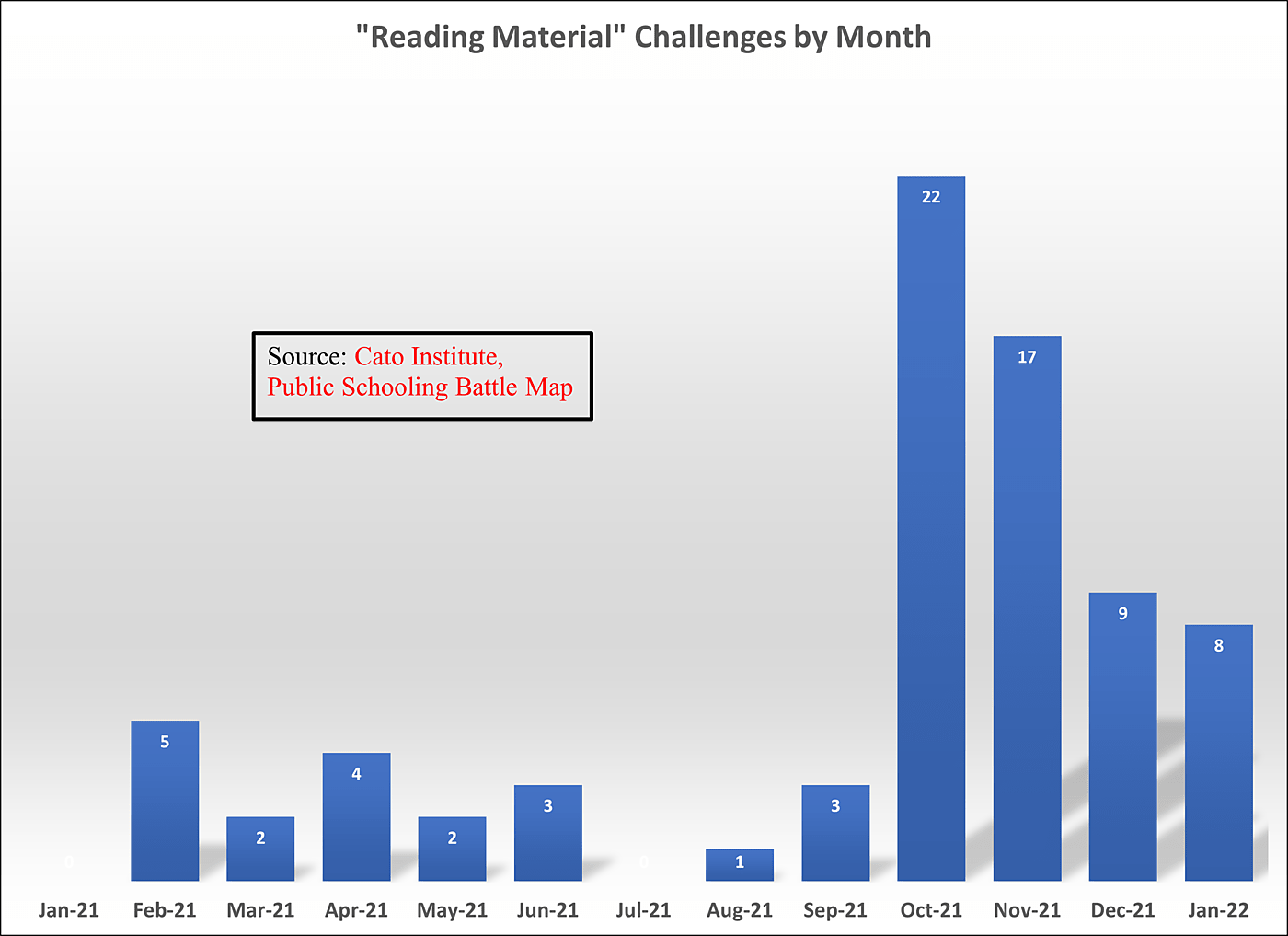

Despite these major issues burning since 2019, most public schooling conflict did not involve specific books until recently. As shown in the following chart, as of the end of June of 2021 the Battle Map database was on pace for a bigger than usual, but not unprecedented, 32 book battles in 2021. By the end of the year the collection had more than doubled that, with a huge spike between September and October.

The spark for the explosion was almost certainly mother Stacy Langton attacking the books Lawn Boy and Gender Queer at the September 23 Fairfax County, VA, school board meeting. In a video that went viral, Langton excoriated the board for the books’ presence in district libraries, mentioning many parts of the volumes she found greatly offensive. Most powerful was likely her highlighting drawings of sexual activity in Gender Queer, a graphic novel containing depictions of minors engaged in sexual acts with adults. Langton said that learning of anger over pornography in schools in Leander, Texas prompted her to search for similar content in Fairfax County, but it was her testimony at the end of September, not the Leander situation at the beginning, that coincided with the big leap in challenges.

How Much Banning: Libraries or Classes?

When discussing book “banning,” it is important to know in what context books in schools are are being challenged.

Importantly, removal of a book from a public school is not a “ban,” in the sense that it has been made illegal for someone to possess it. It is a school or district deciding that it will no longer keep a book in libraries, or on recommended reading lists or assigned in classes. It is not stopping families from buying it on their own.

Of course, schools must make decisions about what books to stock or assign, unless they buy and assign all books ever published, or choose them randomly. Schools, then, are as much “banning” when they do not buy a book because they think its content is unworthy as when they change their worthiness assessment of books they already own. That said, removing books from libraries, in which students presumably have wide options, comes closer to banning than removing books from reading lists, which constrict student choice, and reading assignments, which leave basically no choice.

As the table below shows, of the 103 book challenges we tracked from the beginning of 2021 to about the end of January 2022 (some battles involved multiple titles, but we did not include all of the 850 titles on the Texas list) 76 were over books in libraries. Twenty-two were part of the curriculum.

| Location | Number |

| Library | 76 |

| Part of Curriculum | 22 |

| Under Consideration | 4 |

| Student Brought Book to Class | 1 |

| Total | 103 |

The battles tended to be of the variety coming closest to “banning,” though still far from it.

Ages

Just as there is a spectrum for how much choice schools give students about reading specific books, the range of ages at which children may access or be assigned books matters. Few would disagree that a kindergartner is unable to understand and process the same sexual or racial content as a high school senior. With that in mind, controls on books for younger kids would seem less like “banning” than for older kids.

Of the challenges we tracked, 46 were specifically for high school students (grades 9 to 12) and 33 concerned removing books for all grades in a district. The rest were challenges for specific younger grades, or middle schoolers broadly.

| Grade | Challenges |

| K | 0 |

| 1 | 1 |

| 2 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 |

| 4 | 2 |

| 5 | 1 |

| 6 | 0 |

| 7 | 0 |

| 8 | 0 |

| 9 | 4 |

| 10 | 0 |

| 11 | 0 |

| 12 | 0 |

| 1 to 8 | 3 |

| Middle (6–8) | 6 |

| 7 to 12 | 3 |

| Elementary (K‑6) | 4 |

| High School (9–12) | 42 |

| District-Wide (K‑12) | 33 |

| Under Consideration | 4 |

| Total | 103 |

Just like for libraries versus classes, most challenges have been at broader levels, putting them closer to the “banning” end of the challenge spectrum.

Graphic Novels

What seemed to set off the explosion of challenges was the Fairfax County mother’s complaint about two books, Lawn Boy and Gender Queer. But a specific type of book might be an especially important part of the explosion explanation. Gender Queer is a graphic novel – essentially a large comic book – which means much of its graphic content, including sexual, is truly that: graphic. Maus is also a graphic novel, and its image of a naked woman was a central part of the school board’s decision to stop assigning it. Other graphic novels that have been challenged since January 2021 are Fun Home, Hey Kiddo, Lighter Than My Shadow, The Breakaways, and This One Summer.

Are graphic novels, with their potentially offensive visual content, a big contributor to the book challenge explosion? Almost certainly.

Altogether, we tracked 57 challenged titles, 7 of which were graphic novels, a number that significantly exceeds any past year’s number of such books, which maxed out at 2 and often saw none. Gender Queer was also by far the most opposed book, with 15 challenges. This tracks with growth in graphic novel sales, which grew from around $500 million in 2015 to nearly $900 million in 2020.

LGBTQ and Race

I have not read or analyzed the content of all 57 titles challenged since January 2021, so I have no particular insights into whether specifically LGBTQ sexuality, as opposed to graphic depiction of any sexual conduct, is driving challenges. I also do not know whether challenges to books tackling racial issues can be reasonably seen as wanting to “erase” race, or ugly parts of the country’s history, or are about defending the reputation of police, or moving toward a more colorblind society. But the most frequently challenged books unquestionably have LGBTQ themes, racial, or both.

Again, by far the most frequently challenged book is Gender Queer. All Boys Aren’t Blue, a memoir about a gay African-American man’s experiences growing up, is next, showing up eight times. Lawn Boy, about a gay, biracial young man, is third. Finally, The Hate U Give, about an African-American teen girl’s struggles fitting into white and black communities while also dealing with police brutality, is fourth, with five entries.

Conclusion

There has, indeed, been an explosion of challenges to books over the last few months, and they have tended to cast wide nets over ages and book places. The conditions for the explosion were almost certainly set by COVID-19 frustrations, as well as longstanding racial and cultural tensions that have been spiking since at least the murder of George Floyd. But the final spark appears to have been the literal depiction of sexual activity – perhaps especially because it was LGBTQ, or involving a minor – in the graphic novel Gender Queer.

Of course, the underlying condition for all such values-based conflict is this: Public schooling requires that diverse people fund single schools or districts, leaving them no recourse, when there is deep disagreement, but to fight to make their values the ones acted on and taught. It is the education system itself that is largely to blame.