Whether it’s due to the “China Shock” or “deindustrialization,” a common refrain from those seeking to support American manufacturers and workers via U.S. trade restrictions and subsidies is that these groups have been the helpless victims of “unfettered trade” and “free-market fundamentalism.” As I’ve explained in a series of recent papers, however, this narrative ignores (among other things) the panoply of U.S. laws that already exist to boost the manufacturing sector — laws that, despite their frequent and continued use, just haven’t worked very well in terms of increasing U.S. manufacturing jobs (and, in fact, have likely harmed the U.S. economy, domestic manufacturers, and blue-collar workers).

Chief among those measures is the U.S. antidumping law, which allows domestic manufacturers and unions to request that the government impose special duties on injurious imports allegedly priced below “fair market value” and has been a (deserving) target of criticism here at Cato for more than four decades. Recent economic research has bolstered these criticisms, while demonstrating why any legitimate account of U.S.-China trade policy, the domestic manufacturing sector, and blue-collar jobs must acknowledge and evaluate current U.S. industrial policies before demanding new ones.

- In a July 2020 working paper, economists Alessandro Barattieri & Matteo Cacciatore examined the hundreds of U.S. antidumping measures (and less-frequent “countervailing duty” measures) imposed between 1994 and 2015 and found that duties (1) were concentrated in industrial inputs like primary metals and chemicals; (2) depressed employment in downstream U.S. industries (e.g., steel-users); but (3) provided no long-term benefit for jobs in the protected, upstream industries (e.g., steelmakers). Figure 5 below shows these employment effects. The authors attribute the downstream industries’ job-losses to declining competitiveness caused by higher input and finished goods prices. (Newsflash: water remains wet.)

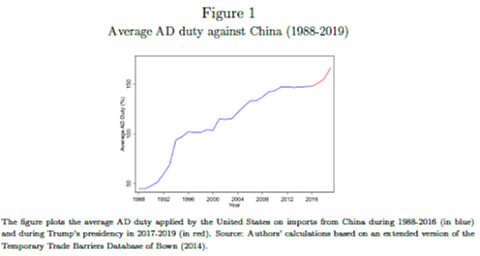

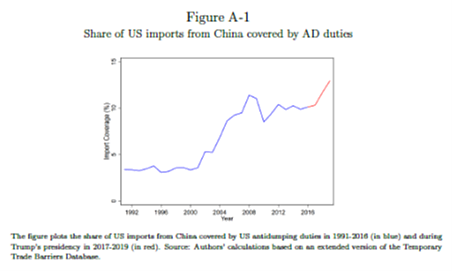

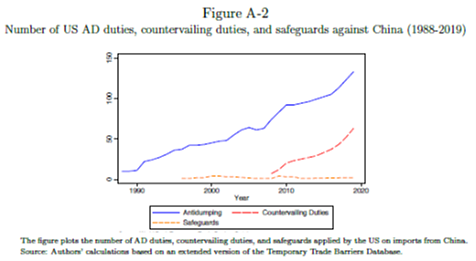

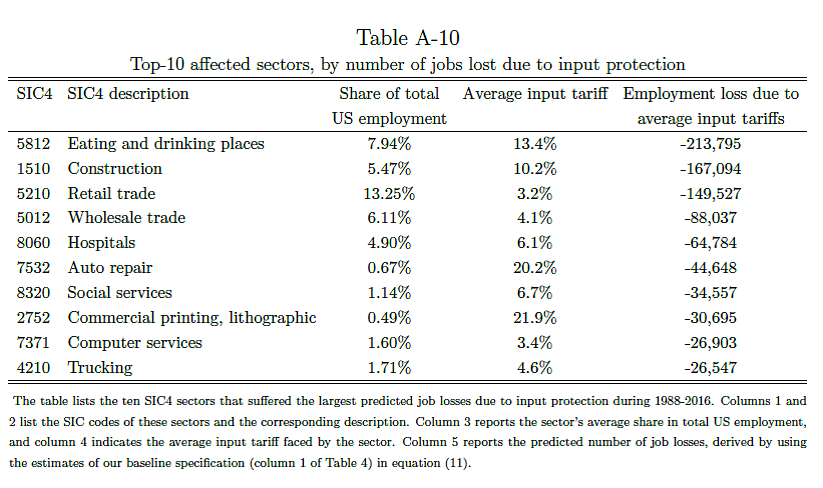

- In a January 2021 paper, economists Chad Bown, Paola Conconi, Aksel Erbahar, and Lorenzo Trimarchi examined antidumping measures on Chinese imports imposed between 1988 and 2016 and found that these duties (1) increased substantially — in terms of duty rates, total import value, and number of measures — over the period examined, and particularly during the height of the “China Shock” in the 2000s (Figures 1, A‑1 and A‑2 below); (2) had large, negative effects on downstream industries in terms of increased production costs and decreased employment, wages, sales, and investment; but (3) had no significant effect on blue-collar jobs, wages, or sales in the protected industries (even though the duties decreased imports and increased foreign and domestic prices). They estimate that the antidumping measures cost approximately 1.85 million U.S. jobs between 1988 and 2016, primarily in blue-collar services industries (though 280,000 manufacturing jobs were also lost). They further provide evidence that duties were often politically motivated, with protection more likely when petitioning companies or workers are located in U.S. “swing states.”

One can quibble with these authors’ exact figures, but the studies’ overall conclusions are consistent with past research showing that U.S. protectionism not only imposes significant economic costs for American companies, workers, and consumers, but also fails to create thriving domestic companies with expanding workforces. The papers also reiterate that any proper accounting of the costs and benefits of open markets generally, or of specific events like the “China Shock,” must consider jobs gained from imports (and lost from protectionism), as well as the longstanding inability of existing U.S. laws — far from “free-market fundamentalism” — to increase blue-collar manufacturing jobs.

Such points are all-too-often missing.