In the long, tragic chronicle of the Great Recession, April 30, 2008, doesn’t resonate as an infamous date. It lacks the notoriety of March 16, 2008, when, by guaranteeing $30 billion of Bear Stearns’ assets, the Federal Reserve crossed a last-resort lending Rubicon, extending its safety net to an investment bank for the very first time. Nor does it conjure up headlines like those of September 15, 2008, when the Fed reversed course by letting Lehman Brothers — a much larger investment bank — go under.

Yet April 30, 2008 was no less critical a turning point in the recession’s history than these other dates, for it was then that the FOMC, having cut the Fed’s target interest rate to 2 percent, resolved to cut it no further — drawing a line in the sand by which it unwittingly helped seal the fate of the US, and world, economy.

At the time neither Fed officials nor anyone else knew that a recession had started, let alone that it was to be the worst recession since the 1930s. Not until December would the NBER’s Business Cycle Dating Committee officially decide that the economy had been shrinking for a year. Instead, having apparently calmed markets by helping to rescue Bear, Fed officials imagined that the worst was over. “When I look at where I was in the last [March] FOMC meeting,” Frederic Mishkin told his fellow FOMC members during that fateful late April gathering, “I sounded so depressed…as though I might take out a gun and blow my head off… . But my sunny, optimistic disposition is coming back…. I think there is a very strong possibility that the worst is over.”

Despite the financial system’s shaky state, what several Fed officials most feared that April was, not a looming recession, but inflation. Between the fall of 2007 and the Fed’s April 30th meeting the CPI inflation rate had jumped from about 2 percent to twice that level. Thanks mainly to rising oil prices, it kept going up well into the summer, when it peaked at 5.5 percent. In response the FOMC’s hawks, led by Dallas Fed President Richard Fisher and Richmond Fed President Jeff Lacker, having already opposed the Fed’s last rate cut in March, refused to support any further cuts, and would keep on successfully opposing them until October.

Ben Bernanke, for his part, was determined to avoid any further public displays of inter-FOMC dissent. To Fed Vice Chair Donald Kohn he privately complained, in an email sent the day after the FOMC’s August meeting, that he found himself “conciliating holders of the unreasonable opinion that we should be tightening even as the economy and financial system are in a precarious position and inflation/commodity pressures appear to be easing.” But he did so, he says in his memoirs, because he worried that too many FOMC dissents would “undermine our credibility.”

Thus the Fed’s monetary policy stance continued to reflect a minority of FOMC members’ preoccupation with inflation even as financial markets began to crumble. To shore up those markets, the Fed supplied over $1 trillion in emergency credit, issued through various emergency lending facilities, to various sorts of financial institutions, while extending a further $85 billion line of credit to AIG. Lending on so vast a scale would normally have flooded the banking system with liquid reserves, causing interest rates to fall in turn. The Fed was nevertheless determined to hold the line it drew that April, and to do it by hook or by crook.

In the event the Fed used both a hook and a crook. The crook consisted of its decision to “sterilize” those emergency loans, yanking-back as many reserves as its emergency loans created by emptying its portfolio of Treasury securities worth as much as the loans it made. That strategy lasted until Lehman’s demise, after which the volume of Fed lending exploded, while its Treasury holdings dwindled. So on October 6th out came the hook, consisting of the Fed’s offer to start paying interest on bank reserves. By paying banks more to hoard reserves than they could make by lending them, the Fed could effectively sequester those reserves, preventing them from contributing to increased lending, spending, and prices.

By then, however, the Fed’s Maginot Line had already been breached. With market interest rates in free fall, the Fed’s 2 percent rate target was mere wishful thinking. Consequently, on the same day that it announced its plan to pay interest on bank reserves, the Fed at last relented by cutting its rate target to 1.5 percent. But no sooner had it done so than reality made a mockery of the new target as well. Eventually the Fed settled on an interest-rate target “range,” with the interest rate paid on bank reserves as its upper bound, and a lower bound of zero. The new target range had at least one undeniable advantage: the Fed couldn’t miss it. But despite that innovation it wasn’t until sometime in November 2008, as the unemployment rate approached 7 percent, that the FOMC determined that monetary stimulus was, after all, just what the economy needed.

The anniversary of a blunder is a good time for taking stock. Could it happen again and, if it could, what can be done to keep it from happening?

The bad news is that it certainly could happen again, and that it probably will happen so long as many Fed officials insist on treating the inflation rate as an all-purpose indicator of the stance of monetary policy. The good news is that there’s a far better alternative, if only the FOMC will use it. That alternative, which Market Monetarists like David Beckworth, Lars Christensen, and Scott Sumner have been pushing ever since the Great Recession started, is for the FOMC to keep its collective eye, not on the inflation rate, but on the level and growth rate of nominal GNP — a measure of the flow of spending on goods and services in the economy. While oil supply shocks and such can cause misleading upsurges in inflation, as happened in the summer of ’08, they don’t make people spend more. Nor, so long as spending grows at a reasonable pace, can money be said to be over-tight. Finally, a Fed that maintains a stable growth rate of spending is less likely to blow an asset-price bubble than one that obsesses over the inflation rate.

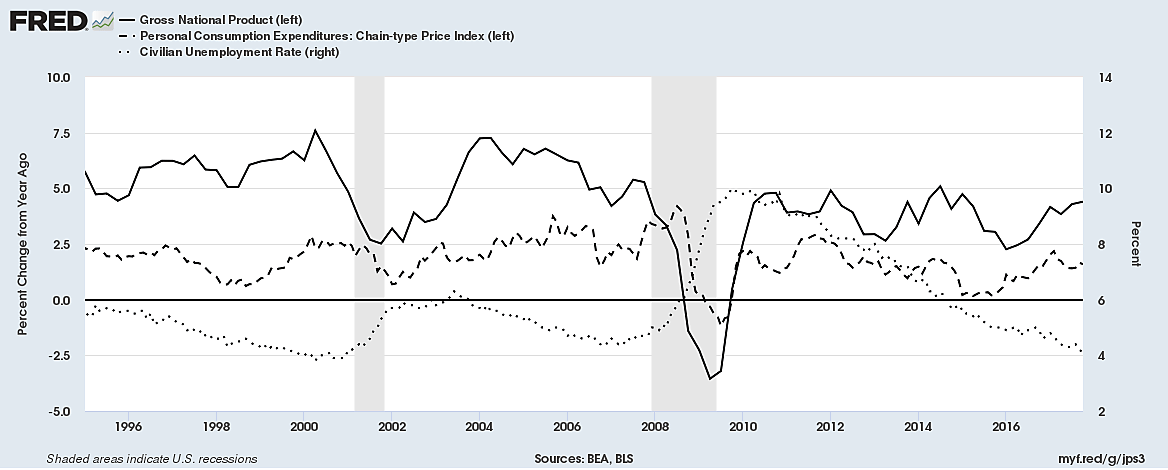

For evidence, consider the chart below, showing (1) the Fed’s preferred inflation measure (the so-called PCE inflation rate) (dashed line), (2) the unemployment rate (dotted line), and (3) nominal GDP growth (solid line), from 1996 until recently. The vertical shaded bars mark the dates of the dot-com and subprime recessions. Suppose that, instead of paying attention to the inflation rate, the Fed had set itself the task, from 1996 onward, of keeping nominal GDP growing at a steady rate of, say, 4.5 percent. Would we have had more or less severe cyclical ups and downs, and accompanying jumps in unemployment? In macroeconomics, nothing is ever perfectly clear. But here, for once, the answer seems clear enough.

It so happens that the latest GDP growth rate figure, for the last quarter of 2017, was just shy of 4.5 percent. So, here is a modest proposal: let the Fed commemorate the decennial of April 30, 2008, by announcing that it intends, henceforth, to devote itself to keeping that growth rate from changing. Would that step solve all of our monetary and macroeconomic problems? Heck no. But it sure could help.

(I thank Sam Bell for his helpful feedback on an earlier version of this article.)