For years Americans have been concerned with rising home prices, and, at least grudgingly, recognized that one way to bring down those costs was to build more housing. But many drew the line on building those new homes in their own neighborhood—what made NIMBY (Not in My Back Yard) one of the most recognized rallying cries in local politics.

A newly released Cato Institute National Survey of 2,000 adults, conducted by YouGov, suggests that the tides may be slowly shifting. The road to housing reform remains bumpy—but it is not impassable.

That is fortunate, because housing affordability is one of the most significant economic issues today and zoning regulations that limit home building are one of the greatest barriers to housing affordability. Without public support, it is difficult to make necessary changes to improve housing supply and reduce costs.

Recent research finds that zoning regulations push up the cost of housing by more than $300,000 or $400,000 per quarter of an acre in cities including San Francisco, Chicago, and Seattle. In New York, the “zoning tax” on housing was estimated at more than $500,000 per quarter of an acre near the urban core in 2018.

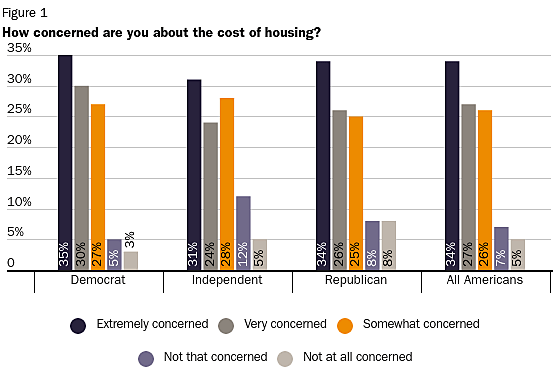

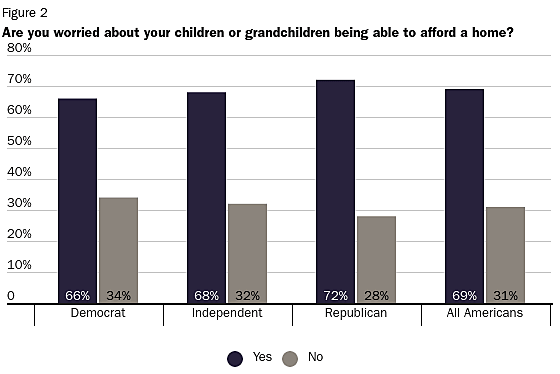

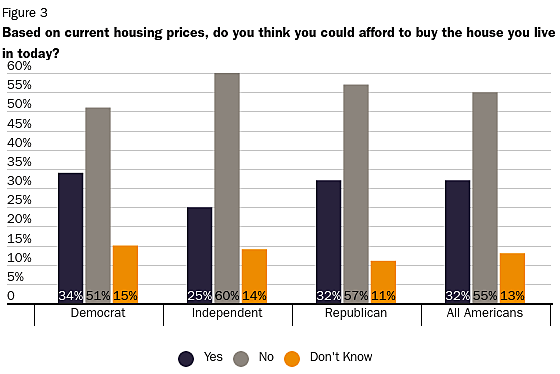

With regulatory burdens that high, interest rates continuing to climb, and continued inflationary pressures on housing, it is no wonder that Americans are deeply concerned about housing costs. In the survey, fully 87 percent of Americans are at least “somewhat concerned” about housing costs, and 61 percent are either “very” or “extremely” concerned. Roughly 69 percent are worried that their children or grandchildren will not be able to afford a home, and a majority of Americans do not believe they could afford to buy the house they live in today.

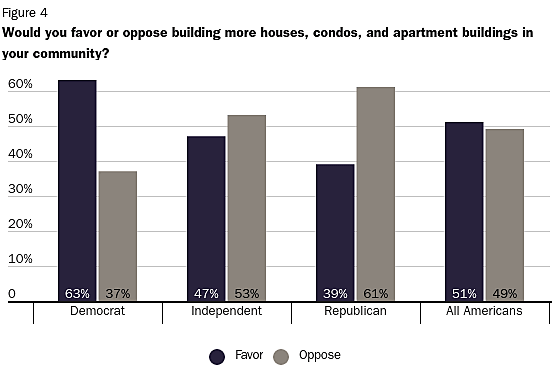

What is more unexpected is that Americans seem increasingly willing to build housing in their back yard. Overall, it is still a close call, with just 51 percent supporting more housing in their own neighborhood. Democrats (63 percent) are more likely to support building more housing, while independents (47 percent) and Republicans (39 percent) are more skeptical.

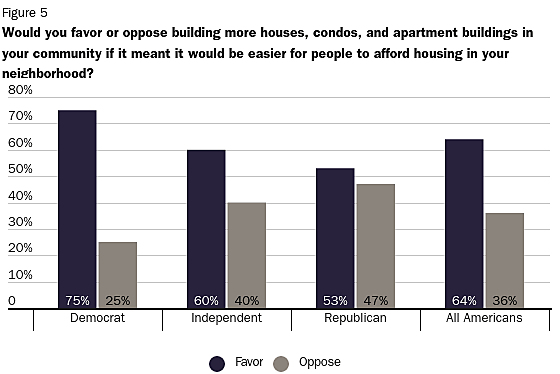

However, support for building housing increases when benefits are mentioned. For example, nearly two-thirds (64 percent) support building more houses, condos, and apartments in their community if it means it would be easier for people to afford housing in their neighborhood. Phrased that way, support for more housing increases among all groups, including Republicans (53 percent).

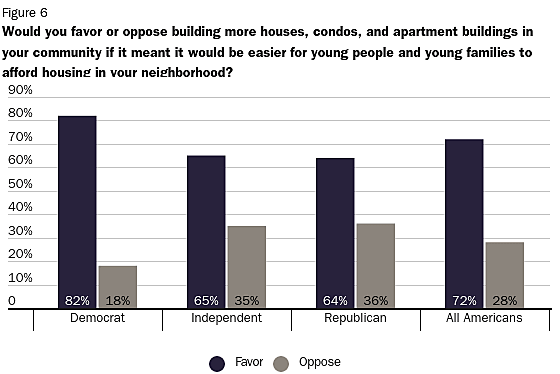

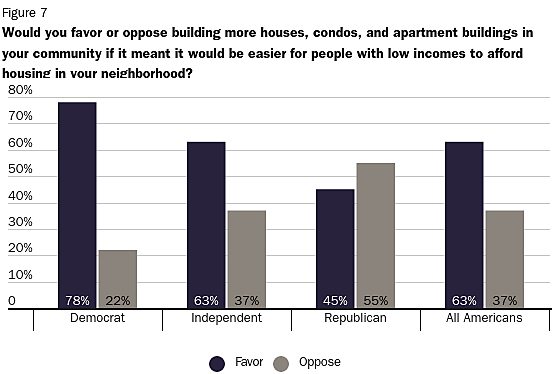

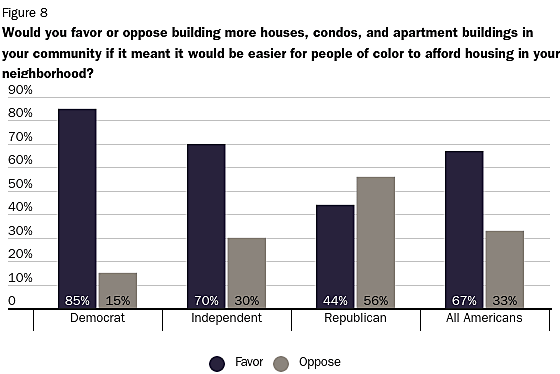

Republicans, more than Democrats or Independents, adjust their support for building more housing based on who they believe will be moving into their neighborhood. For example, when told that more building would make housing affordable for young families, some 64 percent of Republicans were in favor. On the other hand, Republican support declines steeply if it is suggested that the new residents would be low-income (45 percent) or people of color (44 percent). Interestingly, it was this latter argument (that building housing would benefit people of color) that Democrats favored most in the survey, and an extension of this argument motivated liberal Minneapolis’s reform to end single family zoning in 2018.

Regardless of the politics of building more homes, it is worth noting that the evidence supports the idea that relaxing regulatory restrictions to increase housing supply is beneficial for all mentioned groups—both young families, people with lower incomes, and people of color.

For families with young children, not only can reforming zoning alleviate budget pressures and allow growing families to buy or rent the space necessary to live comfortably, but evidence suggests it can also improve school choice for parents. For example, a study found that Houston—the only major city without a traditional zoning code—has lower home prices at every school quality level than other major cities, which indicates greater access to a broader range of schools for young families.

Just as young families have been blocked from critical amenities and educational opportunities as a result of restrictive residential zoning, low-income individuals have also suffered as a result of the practice: previous research finds that restrictive zoning limits home building in economically productive locations with greater job opportunities, and Euclidean zoning is well known to segregate by income.

For people of color, zoning likewise reduces opportunity and access and freezes segregated living patterns in place. In one study, 50 percent of the difference in levels of racial segregation between leniently regulated (less‐segregated) Houston and restrictively zoned (more‐segregated) Boston was a result of restrictive regulation. In another study, reducing zoning regulation was estimated to reduce the difference in racial segregation by at least 35 percent between the most and least segregated areas.

For this and many other reasons, policymakers across the country should marshal current public support for building more homes and make zoning reform a policy priority. Doing so would unlock opportunity for a wide variety of people.