The Washington Post magazine has a lengthy piece on American Indian policy, focusing on the challenges faced by people living on reservations. The cover story by the Post’s David Montgomery highlights the lack of decent services on reservations and discusses federal responsibilities to the tribes that stem from 19th century treaties.

Montgomery describes some of the hardships on the reservations and conveys that federal health, education, and infrastructure services are shoddy. The Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Indian Health Service have long been some of the worst-run federal bureaucracies.

The problem with the Post article is that it does not consider why American Indian reservations do not prosper. It looks backward to broken treaties and lousy federal services, and it quotes tribal leaders complaining about Washington’s broken promises.

But the article does not probe why there is a dearth of self-generated growth on the reservations. It does not ask why reservations are still so dependent on D.C. decades into the modern era of American Indian “self-determination.” The Post story focuses on federal aid, not on reforms that would allow Indian communities to aid themselves.

I discuss some of the institutional reasons why many reservations are poor in this study. Reservations generally lack individual property rights in land, and some lack efficient and impartial government administration. As a result, many reservations have little entrepreneurship, business investment, commercial lending, and real estate development.

About 95 percent of land on American Indian reservations is “trust land.” Individuals do not own this land the way the rest of us own our houses or businesses. Doing anything with trust land needs cumbersome approvals from the BIA. The BIA micromanages reservations with subsidies and regulations. These institutional problems suppress private enterprise.

Montgomery mentions just one example of the micromanagement problem, citing Jonathan Nez, president of the Navajo Nation:

He argues that paternalistic federal regulations undermine the tribe’s sovereignty and hinder progress. For example, it has taken three years and counting to get permission to open a gravel pit so the tribe can efficiently cover dirt roads with gravel, as an interim measure before paving, he says. And fixing roads requires another set of sluggish permissions from Washington. “The frustrating part about it is, sometimes we can’t do what we want to do even on our own sovereign nation,” Nez said. “It doesn’t have to be in the form of dollars. Just change some of those laws so that we can streamline the process and get better quality of services for our people. We have our land — let us utilize it the way we know how.”

Montgomery discusses federal politicians visiting reservations for speeches. But far more useful would be an effort by Congress—in partnership with the tribes—to overhaul the legal structure of reservations. It would be a complex and sensitive process, but what’s the alternative? The current system of dependency, underfunding, and broken political promises is a dead end. Fundamental reform is needed.

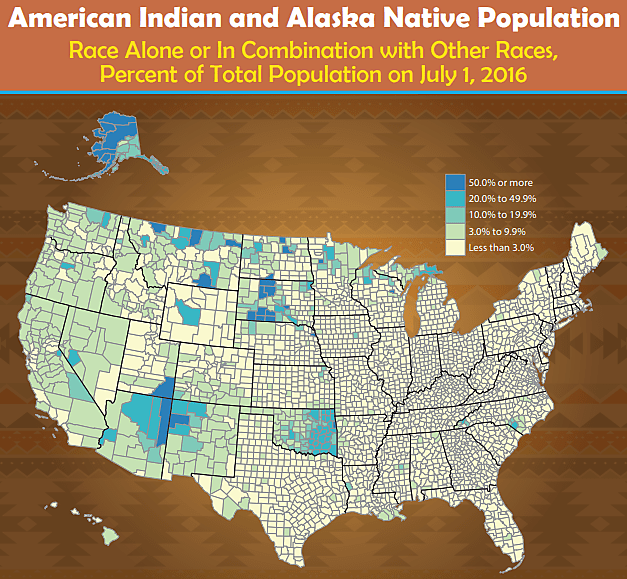

A final quibble with Montgomery’s story: he says there are 6.8 million Native Americans. But his story focuses on reservations, and there are only 1.1 million Native Americans living on reservations. That is why national politicians ignore the chronic problems on reservations—there are relatively few votes.

But votes or not, Congress has a profound responsibility to address American Indian issues—not to hand-out more money but to enact deeper reforms to strengthen individual property rights, efficient legal structures, investment, and entrepreneurship.

For further reading, see my study here, Naomi Schaefer Riley’s book here, and articles by PERC here.