The early April vote by Amazon employees in Bessemer, Alabama to reject unionization – by a 71%-29% margin – has resulted in soul-searching among organized labor advocates and now formal objections filed by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union, alleging to the National Labor Relations Board that “Amazon intimidated and threatened employees into voting against unionizing.” Few labor activists can believe, it seems, that workers in Bessemer would willfully, thoughtfully, and overwhelmingly turn down the chance to join the union and reap its supposed benefits. Nefarious actions must therefore be at play.

Such disbelief, however, is unwarranted — steeped in a nostalgic view of “good blue collar jobs” being only unionized ones in manufacturing and ignoring all of the other “good jobs” that have emerged since the heyday of private sector unions, especially in services or the lower-cost, right-to-work South. With these blinders removed, one can see broader trends in the U.S. labor market and specific ones in Alabama that show why unionizing Amazon’s Bessemer facility always should’ve been considered a longshot. In short, this isn’t the 1970s anymore, and these jobs are already good jobs – especially in Alabama.

As discussed here previously, warehouse and e‑commerce jobs like those at Amazon are not only increasing in number, but also increasingly well-paid: since 2013 (the start of the “e‑commerce era”), gains in hourly earnings for production and nonsupervisory workers in the warehousing industry far outpaced those in manufacturing, trucking, and the private sector generally, and blue collar workers in warehousing now earn more than their counterparts in the manufacturing sector. Subsequent research from the Progressive Policy Institute’s Michael Mandel finds that “most Americans live in states where the tech-ecommerce ecosystem pays better than manufacturing.”

In fact, occupational data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that it paid more – much more – in 2020 to help move the proverbial “cheap t‑shirt” from place to place in America than it did to make it:

The situation with Amazon in Alabama is just as stark as the national data above, if not more so. In particular, the same BLS occupational data show that Amazon’s starting hourly wage ($15) in 2020 was far higher than 10th percentile (presumably starting) wages in manufacturing (all occupations), production occupations (all sectors), and the private sector overall, and it was almost as high as the median hourly wage in Alabama for those same workers:

These BLS data further show that Amazon’s starting wage is higher than the 10th percentile wage for production occupations in 73 of 79 manufacturing industries (NAICS codes 31–33) in Alabama and higher than the median wage in 29 of those same 79 occupational categories. Those hourly Amazon jobs, of course, also have health and retirement benefits that many lower-wage jobs lack. PPI’s data on all e‑commerce jobs (not just warehousing) show similar job growth and pay premiums in the state – ranking it 11th overall in terms of these jobs’ share of total private sector job growth over the last decade or so.

Given these data, and the repeated statements from Amazon-Bessemer workers themselves attesting to the relatively good pay and benefits at the facility (and questioning how a union would make things even better), it’s no wonder that the vote came out the way it did. Surely, life isn’t perfect there (it rarely is anywhere), but why mess with a pretty good thing? In fact, it’d be surprising if the vote had turned out otherwise – surprise eluding, it seems, only those who can’t conceive of a relatively-free U.S. labor market generating good jobs without significant unionization or government interventions, or a large American employer with, as one labor lawyer put it to the Wall Street Journal, “the power and the capital to pay competitively, survey employees about their experiences and respond to dissatisfaction before it grows.”

Heaven forbid.

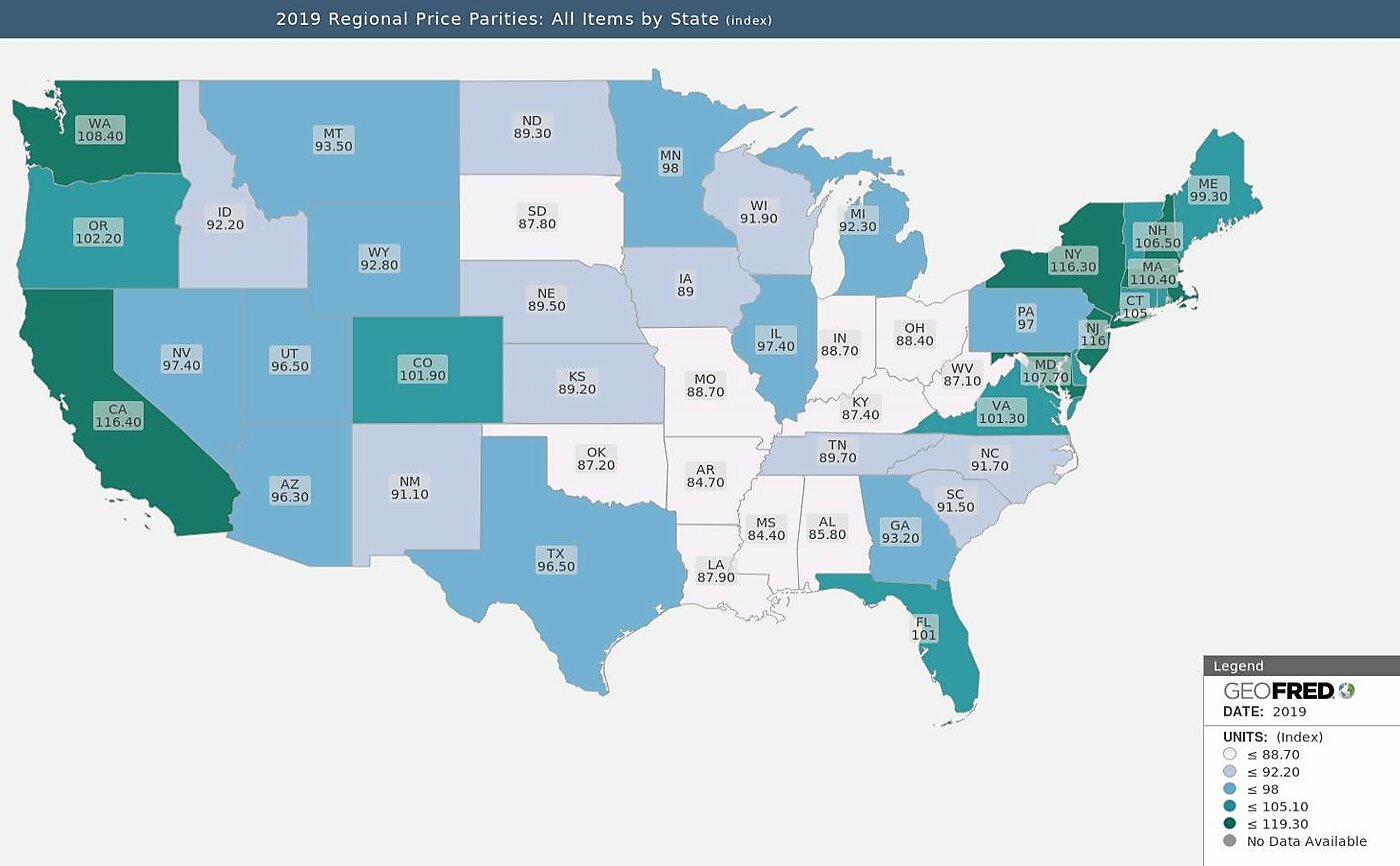

One last note: the BLS data above are sure to elicit (and indeed already have) the usual lament about low wages (and the destruction of “good jobs”) in horrible, no-good Alabama. Before indulging in such criticism, one should consider how Alabama’s extremely low cost of living allows Amazon paychecks to stretch a lot further than they would in higher-cost places. For example, the Bureau of Economic Analysis Regional Price Parities, which allow for comparison of cost-of-living differences across various geographic areas, ranked Alabama as the third cheapest state in the country in 2019 (the last year available), behind only Arkansas (2) and Mississippi (1).

Economists routinely use RPPs to calculate “real” living standards across the United States, essentially by applying the RPP for the region at issue to wages or incomes in that area to arrive at an adjusted value that shows what local pay would be in a place where price levels are equal to the national average (100 in the map above). Applying Alabama’s 2019 RPP to Amazon’s $15 minimum wage raises it to an adjusted hourly wage of $17.48, and the RPP-adjusted median hourly wage in the state in 2019 was $19.50 – higher than the 2019 national median hourly wage ($19.14) and much higher than the adjusted median hourly wage in high-cost and union-friendly California ($18.25) that same year.

Maybe Amazon’s model wouldn’t work well in California, but it can in Alabama – and 71 percent of Bessemer employees seem to agree.