Private school choice is the work of racists. That message, it seems increasingly clear, is going to be a major weapon wielded by opponents of educational freedom for the foreseeable future. It is the explicit contention of a new Center for American Progress report, The Racist Origins of Private School Vouchers, and of Randi Weingarten, President of the American Federation of Teachers, who has been proclaiming that modern choice programs are “only slightly more polite cousins of segregation.”

As I and others have written, the assertion that school choice originated in racism, or somehow has a more repellant history than public schooling, would be laughable if the implications of the charge were not so serious. Remember, Brown v. Board of Education was about massive, mandated segregation in public schools, the schools that defenders love to tell us serve the vast majority of students. Segregation in them meant—and means—segregation for huge swaths of people. Perhaps that is why a response to my critique of the CAP report from the Century Foundation’s Kimberly Quick focused not on history, but my pointing out that private school choice is popular with African Americans.

According to Quick this is not so, and by the way, on what grounds does someone at Cato speak “on behalf of the black community”? Cato has no African American policy scholars.

I never wrote that I speak on behalf of African Americans. I do not presume to speak for anyone other than myself. But the survey literature—African Americans speaking for themselves—is overwhelmingly on my side.

To demonstrate that polls do not show majority African American support for private school choice, Quick cites the oft-used question from the annual Phi Delta Kappa poll, which employs wording notoriously loaded against choice: “Do you favor allowing students and parents to choose a private school to attend at public expense.” “At public expense” sounds like freeloading, and “choose a private school” rather than to choose among schools minimizes the empowerment of families. Not surprisingly, this wording garners only 33 percent African-American support, though that outpaces the general public.

What is much more telling is what the polling reveals when the question is more neutral, which excludes surveys that get both high negative and positive numbers. What follows is not an exhaustive list, and there are other ways to game survey outcomes such as question order, but there have been many, more neutrally worded surveys that have shown that African Americans want private school choice.

The journal Education Next has for several years asked questions both neutral and not so neutral to gauge school choice support. As I noted in my initial response to the CAP paper, the 2016 survey found “a whopping 64 percent of African Americans supported ‘a tax credit for individual and corporate donations that pay for scholarships to help low-income parents send their children to private schools.’” The 2015 survey revealed that 58 percent of African Americans favored a program “that would give all families with children in public schools a wider choice, by allowing them to enroll their children in private schools instead, with the government helping to pay the tuition.” 66 percent supported a similar program just for low-income families, and even when using wording closer to PDK’s, pluralities of African Americans supported it. In 2016 EdChoice asked three forms of a question about vouchers, and the composite average was 61 percent of African Americans favoring them.

The Black Alliance for Educational Options has also conducted polling, with very straightforward wording, such as “do you support or oppose parent choice,” and “do you support school vouchers/scholarships?” Asking African Americans in New Jersey, Tennessee, Alabama, and Louisiana these questions, in 2015 BAEO reported support ranging from 61 percent to 65 percent, depending on the state.

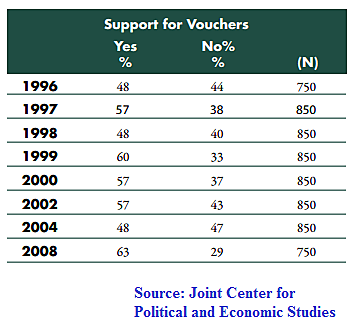

Of course, EdChoice and BAEO advocate for school choice, and Education Next features many choice proponents. But some of the longest running evidence of African-American support for choice comes from the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, “a non-partisan, non-profit public policy organization that supports elected officials and policy experts who serve communities of color across the country.” Over many years it has consistently found plurality to significant majority African-American support for choice. Its most recent poll of which I am aware, conducted in 2008, reported that 63 percent of respondents said “yes” when asked if they “support vouchers.” At least in 2000, the exact question asked was, “Would you support a voucher system where parents would get money from the government to send their children to the public, private, or parochial school of their choice?” (I haven’t been able to confirm the question for other years.)

Perhaps all of this is why Quick’s colleague Richard Kahlenberg recently said in answer to a question I asked about black support for school choice, his understanding of the polling was the same as mine: African Americans want choice. (Or so I recall—I’m not sure if event video will be up to confirm this.) Indeed, Quick herself concedes that “it makes sense that black and brown families, too often lacking options beyond segregated, under resourced, and underperforming schools, would want alternative options for their children.”

Now, about Cato for a moment. Again, I claim no insight based on personal experience into what African Americans individually or collectively want, and I certainly wish there were more black libertarians. But when I first started working at Cato, a major player in the fight for choice in Washington, DC, was Casey Lartigue, an African American Cato scholar. Similarly, Jonathan Blanks, a Cato researcher, who is African American and recently wrote that libertarians must not downplay racism or think it will be overcome just by free markets, but school choice is nonetheless important for the black community. Of course, none of this makes choice right or wrong, nor does it make Cato any more or less a spokes-tank for African Americans.

I’ll let the evidence, and individual African Americans, speak and act for themselves. Indeed, empowering the formerly powerless to act for themselves is exactly what school choice is about.