This Current Wisdom takes an in-depth look at how politics can masquerade as science.

“A pack of foma,” Bokonon said

Paraphrased from Cat’s Cradle (1963), Kurt Vonnegut

In his 1963 classic, Cat’s Cradle, iconic writer Kurt Vonnegut described the sleepy little Caribbean island of San Lorenzo, where the populace was mesmerized by the prophet Bokonon, who created his own religion and his own vocabulary. Bokonon communicated his religion through simple verses he called “calypsos.” “Foma” are half-truths that conveniently serve the religion, and the paraphrase above is an apt description of the Administration’s novel approach to determining the “social cost of carbon” (dioxide).

Because of a pack of withering criticism, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) is now in the process of reviewing how the Obama Administration calculates and uses the social cost of carbon (SCC). We have filed a series of Comments with the OMB outlining what is wrong with the current SCC determination. Regular readers of this blog are familiar with some of the problems that we have identified, but our continuing analysis of the Administration’s SCC has yielded a few more nuggets.

We describe a particularly rich one here—that the government wants us to pay more today to offset a modest climate change experienced by a wealthy future society than to help alleviate a lot of climate change impacting a less well-off future world.

This kind of logic might be applied by Bokonon on San Lorenzo, but here in sophisticated Washington? It is exactly the opposite of what a rational-thinking person would expect. In essence, the Obama Administration has turned the “social cost” of the social cost of carbon on its head. The text below, describing this counterintuitive result, is adapted from our most recent set of Comments to the OMB.

The impetus behind efforts to determine the “social cost of carbon” is generally taken to be the desire to quantify the “externalities,” or unpaid future costs, that result from climate changes produced from anthropogenic emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. Such information could be a useful tool in guiding policy decisions regarding greenhouse gas emissions—it if were robust and reliable.

However, as is generally acknowledged, the results of such efforts (generally through the development of Integrated Assessment Models, IAMs) are highly sensitive not only to the model input parameters but also to how the models have been developed and what processes they try to include. One prominent economist, Robert Pindyck of M.I.T. recently wrote (Pindyck, 2013) that the sensitivity of the IAMs to these factors renders them useless in a policymaking environment:

Given all of the effort that has gone into developing and using IAMs, have they helped us resolve the wide disagreement over the size of the SCC? Is the U.S. government estimate of $21 per ton (or the updated estimate of $33 per ton) a reliable or otherwise useful number? What have these IAMs (and related models) told us? I will argue that the answer is very little. As I discuss below, the models are so deeply flawed as to be close to useless as tools for policy analysis. Worse yet, precision that is simply illusory, and can be highly misleading.

…[A]n IAM-based analysis suggests a level of knowledge and precision that is nonexistent, and allows the modeler to obtain almost any desired result because key inputs can be chosen arbitrarily.

Nevertheless (or perhaps because of this), the federal government has now incorporated IAM-based determinations of the SCC into many types of new and proposed regulations.

The social cost of carbon should simply be the fiscal impact on future society that human-induced climate change from greenhouse gas emissions will impose. Knowing this, we (policymakers and regular citizens) can decide how much (if at all) we are willing to pay currently to reduce the costs to future society.

Logically, we are probably more willing to sacrifice more now if we know that future society would be impoverished and suffer from extreme climate change, than we would if we knew that the future held minor or modest climate changes impacting a society that will be very well off. We would expect that the value of the social cost of carbon would reflect the difference between these two hypothetical future worlds—the SCC should be far greater in an impoverished future facing a high degree of climate change than an affluent future confronted with much less climate change.

But if you thought this, you would be wrong. This is Bokononism.

Instead, the IAMs, as run by a federal “Interagency Working Group” (IWG) produce nearly the opposite result— that is that the SCC is far lower in the less affluent/high climate change future than it is in the more affluent/low climate change future. Bokonon says it is so.

We illustrate this illogical and impractical result using one of the Integrated Assessment Models used by the IWG—a model called the Dynamic Integrated Climate-Economy model (DICE) that was developed by Yale economist William Nordhaus. The DICE model was installed and run at the Heritage Foundation by Kevin Dayaratna and David Kreutzer using the same model set up and emissions scenarios as prescribed by the IWG. The DICE projections of future temperature change were provided to us by the Heritage Foundation.

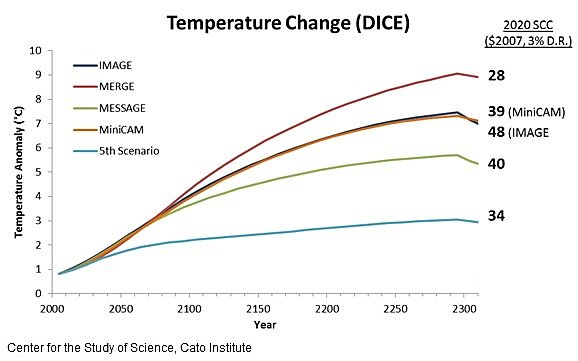

Contrary to Einstein’s dictum, Bokonon does throw DICE. Figure 1 shows DICE projections of the earth’s average surface temperature for the years 2000–2300 produced by using the five different scenarios of how future societies develop (and emit greenhouse gases).

Disregard the fact that anyone who thinks we can forecast the future state of society 100 years from now (much less 300) is handing us a pack of foma. Heck, 15 years ago everyone knew the world was running out of natural gas.

The numerical values on the right-hand side of the illustration are the values for the social cost of carbon associated with the temperature change resulting from each emissions scenario (the SCC is reported for the year 2020 using constant $2007 and assuming a 3% discount rate). The temperature change can be considered a good proxy for the magnitude of the overall climate change impacts.

Figure 1. Future temperature changes, for the years 2000–2300, projected by the DICE model for each of the five emissions scenarios used by the federal Interagency Working Group. The temperature changes are the arithmetic average of the 10,000 Monte Carlo runs from each scenario. The 2020 value of the SCC (in $2007) produced by the DICE model (assuming a 3% discount rate) is included on the right-hand side of the figure. (DICE data provided by Kevin Dayaratna and David Kreutzer of the Heritage Foundation).

Notice in Figure 1 that the value for the SCC shows little (if any) correspondence to the magnitude of climate change. The MERGE scenario produces the greatest climate change and yet has the smallest SCC associated with it. The “5th Scenario” is one that holds climate change to a minimum by imposing strong greenhouse gas emissions limitations yet a SCC that is more than 20% greater than the MERGE scenario. The global temperature change by the year 2300 in the MERGE scenario is 9°C while in the “5th Scenario” it is only 3°C. The highest SCC is from the IMAGE scenario—a scenario with a mid-range climate change. All of this makes sense only to Bokonon.

If the SCC bears little correspondence to the magnitude of future human-caused climate change, than what does it represent?

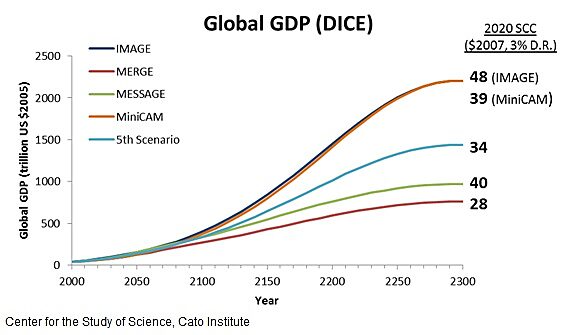

Figure 2 provides some insight.

Figure 2. Future global gross domestic product, for the years 2000–2300 for each of the five emissions scenarios used by the federal Interagency Working Group. The 2020 value of the SCC (in $2007) produced by the DICE model (assuming a 3% discount rate) is included on the right-hand side of the figure.

When comparing the future global gross domestic product (GDP) to the SCC, we see, generally, that the scenarios with the higher future GDP (most affluent future society) have the higher SCC values, while the futures with lower GDP (less affluent society) have, generally, lower SCC values.

Combining the results from Figures 1 and 2 thus illustrates the absurdities in the federal government’s (er, Bokonon’s) use of the DICE model. The scenario with the richest future society and a modest amount of climate change (IMAGE) has the highest value of the SCC associated with it, while the scenario with the poorest future society and the greatest degree of climate change (MERGE) has the lowest value of the SCC. Only Bokononists can understand this.

This counterintuitive result occurs because the damage functions in the IAMs produce output in terms of a percentage decline in the GDP—which is then translated into a dollar amount (which is divided by the total carbon emissions) to produce the SCC. Thus, even a small climate change-induced percentage decline in a high GDP future yields greater dollar damages (i.e., higher SCC) than a much greater climate change-induced GDP percentage decline in a low GDP future.

Only Bokonon would want to spend (sacrifice) more today to help our rich descendants deal with a lesser degree of climate change than to help our relatively less-well-off descendants deal with a greater degree of climate change.

Yet that is what the government’s SCC would lead you to believe and that is what the SCC implies when it is incorporated into federal cost/benefit analyses.

In principle, the way to handle this situation is by allowing the discount rate to change over time. In other words, the richer we think people will be in the future (say the year 2100), the higher the discount rate we should apply to damages (measured in 2100 dollars) they suffer from climate change, in order to decide how much weshould be prepared to sacrifice today on their behalf.

Until (if ever) the current situation is properly rectified, the federal government’s determination of the SCC is not fit for use in the federal regulatory process as it is deceitful and misleading.

Tiger got to hunt

Bird got to fly

Man got to sit and wonder why, why, why.

Tiger got to sleep

Bird got to land

Man got to tell himself he understand.

‑Foma in a Bokonon’s Calypso

References:

Nordhaus, W. 2010. Economic aspects of global warming in a post-Copenhagen environment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107(26): 11721–11726.

Pindyck, R. S., 2013. Climate Change Policy: What Do the Models Tell Us? Journal of Economic Literature, 51(3), 860–872.