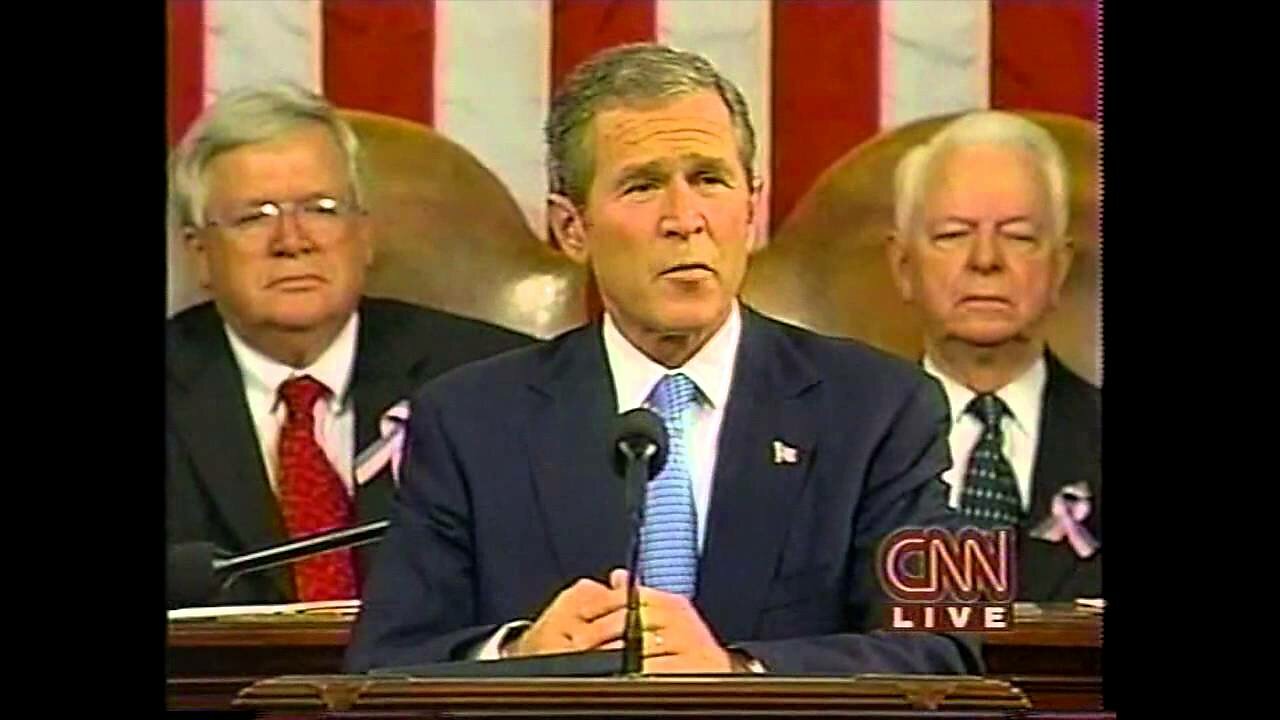

Over the last decade and a half, we’ve heard over and over again that “September 11th changed everything”—but maybe September 14 was the pivotal date. Sixteen years ago today, Congress passed the 2001 Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF). Aimed at the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks and those who “harbored” or “aided” them, the AUMF has been transformed into an enabling act for globe-spanning presidential war.

“I don’t think one generation should bind another generation to war,” Sen. Rand Paul (R‑KY) insists, but that’s exactly what’s happened: the AUMF Congress passed in 2001 still serves as legal cover for “current wars we fight in seven countries.”

Sixteen years ago, Barack Obama was an unknown state senator and part time law professor, and Rep. Gary Condit (D‑CA) was, up till 9/11, the biggest story in American politics. Steve Jobs had yet to introduce the first iPod, and some people thought it was the Segway that was really going to “change everything.” In that faraway time, believe it or not, the federal government actually had a budget surplus.

Two-thirds of the House members who voted for the 2001 AUMF and three quarters of the Senate are no longer in Congress today. But judging by what they said at the time, the legislators who passed it didn’t think they were committing the US to an open-ended, multigenerational war. They thought they were targeting Al Qaeda and the Taliban. The 2001 AUMF was nothing like the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution that underwrote the Vietnam War, then-Sen. Joe Biden (D‑DE) insisted after the vote: “we do not say pell-mell, ‘Go do anything, any time, any place.’”

The 2001 AUMF has now been in effect over twice as long as the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, and three imperial presidents in a row have stretched it into the boundless grant of power Biden disclaimed: broad enough to cover an ever-expanding succession of “associated forces” (a term absent from the AUMF), as well as everything from “boots on the ground in the Congo” to drones over Timbuktu.

Undeclared wars and drive-by bombing raids were hardly unknown before 9/11. But most of the military excursions of the post-Cold War era were geographically limited, temporary departures from a baseline of peace. No longer: war is now America’s default setting; peace, the dwindling exception to the rule.

Barack Obama left office as the first two-term president in American history to have been at war every single day of his presidency. In his last year alone, U.S. forces dropped over 26,000 bombs on seven different countries.

Seven months into his presidency, Donald Trump has almost certainly passed Obama’s 2016 tally already. The Trump administration used the AUMF for an additional troop surge against the Taliban, in the never-ending quest to “Make Afghanistan Great Again,”—and may yet use that authority for airstrikes in the Philippines. The administration recently sent a letter to Sen. Bob Corker (R‑TN), chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, suggesting they view the authorization as broad enough to underwrite the use of force against the Assad regime in Syria. Moreover, they’re “not seeking revisions to the 2001 AUMF or additional authorizations to use force.” And why would they? As Lyndon Johnson once cracked about the Gulf of Tonkin resolution, like “grandma’s nightshirt,” it’s big enough to cover everything.

“Ten to 20 years” is the standard, recurring answer Pentagon officials give, whenever they’re asked how long the various wars on terror will go on, perhaps “a generation or more.” The droning will continue until morale improves.

Convinced that at least once a generation, Congress should vote on the multiple wars we’re fighting, this week Senator Paul forced that vote by threatening to hold up the Defense appropriations act. Yesterday, Paul’s amendment sunsetting the existing war authorization after six months went down to defeat, 61–36.

Sen. Jeff Flake (R‑AZ), explained his vote to scuttle Paul’s amendment in terms of the “real risk associated with repealing such a vital law before we have a something to replace it with.” If it’s such a vital law and they’re such vital wars, presumably Congress could motivate itself to address the issue in the space of six months, and would be more likely to act if forced to. Still, Flake expects Senator Corker to hold hearings on repealing and replacing the AUMF in the near future.

We’ll see. The debate can’t end with the defeat of Paul’s amendment—if it does, he warns, we’ll find ourselves embroiled in far-flung conflicts and foreign occupations “another 16 years down the road.”