Eighty-four percent (84%) of Americans oppose civil asset forfeiture–police “taking a person’s money or property that is suspected to have been involved in a drug crime before the person is convicted of a crime,” according to a new Cato Institute/YouGov survey of 2,000 Americans. Only 16% think police ought to be allowed to seize property before a person is convicted.

Civil asset forfeiture is a process by which police officers seize a person’s property (e.g. their car, home, or cash) if they suspect the individual or property is involved with criminal activity. The individual does not need to be charged with, or convicted of, any crime for police to seize assets.[1] In most jurisdictions police departments may keep the property they seize or the proceeds from its sale. However, as these survey results demonstrate, most Americans oppose this practice.

Find the full public opinion report here

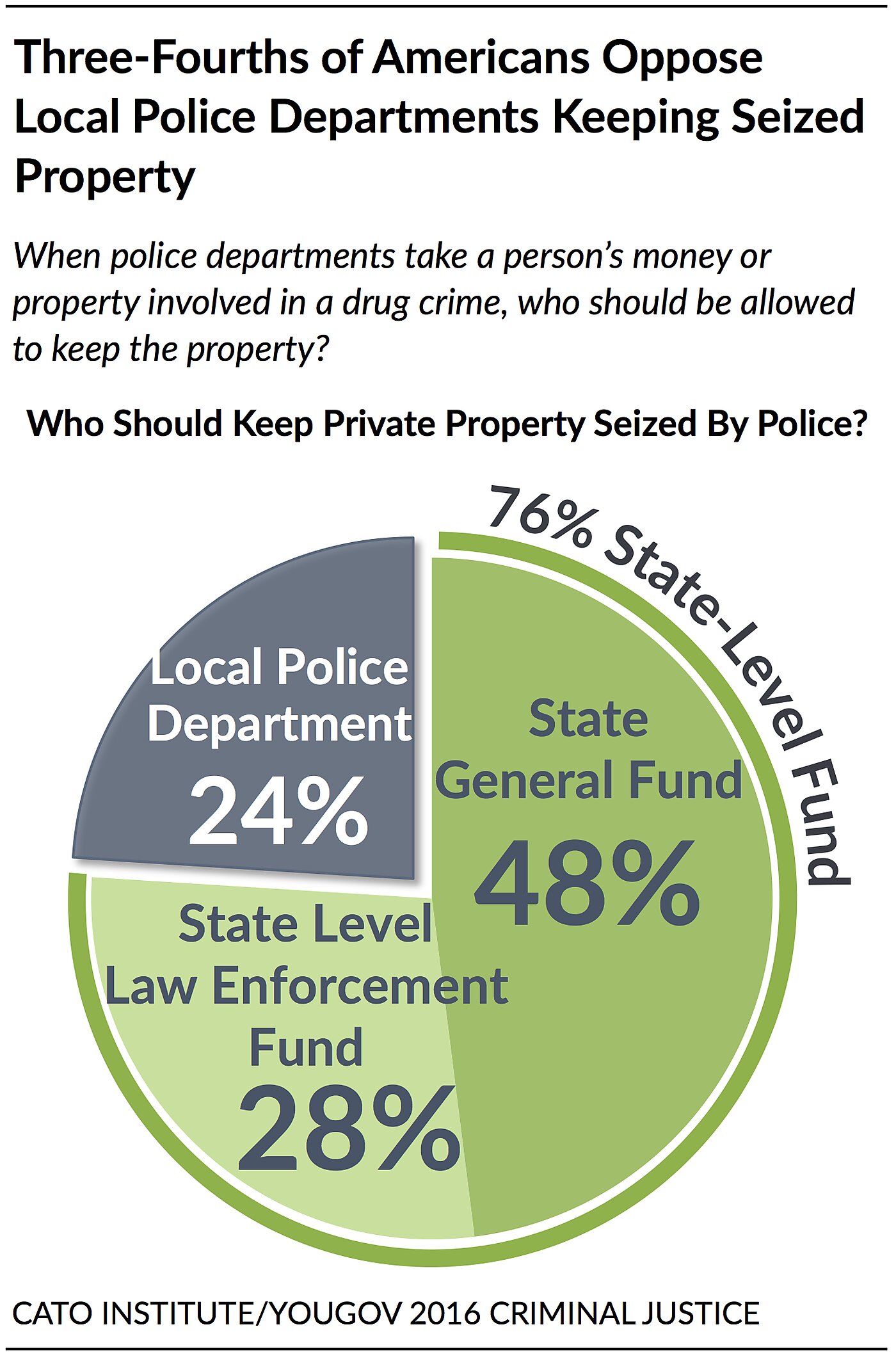

In instances when police departments seize people’s cars, houses, or cash, 76% of Americans say local departments should not be allowed to keep the assets. Instead, 48% say seized assets should go into the state general fund, while another 28% say assets should go into a dedicated state-level general law enforcement fund.

Although Americans prefer policing be done by local (not state or federal) authorities, only 24% think local police departments should keep the assets they seize. [2] Americans may believe transferring seized assets to a state-level fund will reduce local departments’ material incentive to seize people’s property.

Opposition to civil asset forfeiture cuts across demographics and partisanship. Strong majorities of whites (84%), blacks (86%), Hispanics (80%), Democrats (86%), independents (87%), and Republicans (76%) all oppose. In fact, virtually every major group surveyed solidly rejects the practice and prefers property only be seized after a person is convicted of a crime. Even those highly favorable toward the police staunchly oppose (78%) civil asset forfeiture.

Few understand the concept of civil asset forfeiture. Yet, once the concept is explained to them in concrete terms the public overwhelmingly rejects the practice. Thus, reformers’ primary challenge is informing the public that this practice occurs. Policy reforms may follow broader public knowledge of civil forfeiture.

The Cato Institute/YouGov national survey of 2000 adults was conducted June 6–22, 2016 using a sample drawn from YouGov’s online panel, which is designed to be representative of the US population. YouGov uses a method called sample matching, and restrictions are put in place to ensure that only the people selected and contacted by YouGov are allowed to participate. The margin of sampling error for all respondents is +/-3.19 percentage points. The full report can be found here, toplines results can be found here, full methodological details can be found here.

div[1] The legal rationale is that the property itself may be involved in a crime, and thus must be seized. However in practice, since property can be seized without charging a person with a crime or convicting them, many innocent people have had their property taken from them without due process. See Marian R. Williams et al, “Policing for Profit: The Abuse of Civil Asset Forfeiture,” Institute for Justice, March 2010, http://www.ij.org/images/pdf_folder/other_pubs/ assetforfeituretoemail.pdf; “Civil Asset Forfeiture: 7 Things You Should Know,” Heritage Foundation Factsheet no. 141, March 26, 2014, http://thf_media.s3.amazonaws.com/2014/pdf/FS_141.pdf.

div[2] John Samples and Emily Ekins, “Public Attitudes toward Federalism: The Public’s Preference for Renewed Federalism,” Cato Institute Policy Analysis no. 759, September 23, 2014, http://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/public-attitudes-towar….