An important portion of President Trump’s immigration enforcement policy is immigrant detention. Immigrants who are apprehended at the border or in the interior of the United States are detained in Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) facilities until they are removed from the United States. In recent months, many reports have surfaced of immigrants who have died while in detention or shortly after being released to medical facilities for treatment. The rate of death in ICE detention facilities is an important metric of how humane those facilities are.

There are two primary pieces of data required to calculate the death rate in immigration detention: The number of people in detention each year and the number of deaths. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) runs all of the detention facilities and they provide the number of deaths and admissions. The American Immigration Law Association provides some more recent numbers of deaths in detention, but I only include those that ICE also counts. The admissions into ICE detention facilities variable is closest to the number of unique individuals who were present in a detention facility in each year. The numbers for both variables run through the end of Fiscal Year (FY) 2019.

Eight people died in immigration detention in FY2019, down from 10 in FY2018. During the same time, the number of admissions into ICE detention facilities increased from 396,488 to 510,854 (Table 1). The FY2019 death rate in ICE immigration detention was 1.6 per 100,000 detainees, a 38 percent drop from FY2018. That’s good news, but is likely the result of so many younger asylum seeker with fewer health problems being detained along the border rather than improved detention conditions.

Table 1

Deaths in ICE Detention, Death Rates, Detentions

|

Fiscal Year |

Deaths |

Death Rate (per 100,000 detentions) |

Detentions |

|

2004 |

28 |

11.9 |

235,247 |

|

2005 |

21 |

8.8 |

237,667 |

|

2006 |

19 |

7.4 |

256,842 |

|

2007 |

12 |

3.9 |

311,169 |

|

2008 |

11 |

2.9 |

378,582 |

|

2009 |

14 |

3.7 |

383,524 |

|

2010 |

8 |

2.2 |

363,064 |

|

2011 |

10 |

2.3 |

429,247 |

|

2012 |

8 |

1.7 |

477,523 |

|

2013 |

9 |

2.0 |

440,557 |

|

2014 |

6 |

1.4 |

425,728 |

|

2015 |

7 |

2.3 |

307,342 |

|

2016 |

10 |

2.8 |

352,882 |

|

2017 |

12 |

3.7 |

323,591 |

|

2018 |

10 |

2.5 |

396,448 |

|

2019 |

8 |

1.6 |

510,854 |

|

Total |

193 |

3.3 |

5,830,267 |

Sources: ICE and Author’s Calculations.

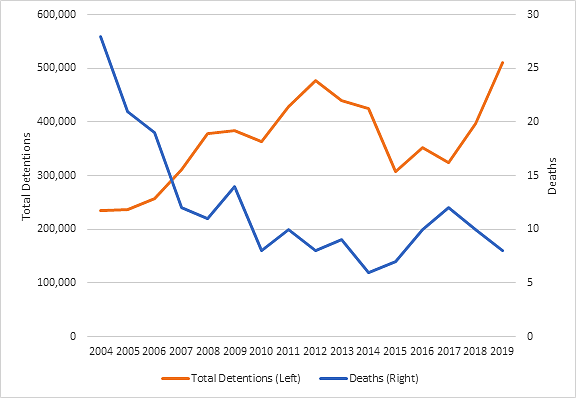

Figure 1 shows the total number of ICE detentions and the total number of deaths in custody. The deaths in ICE detention facilities were highest during the George W. Bush administration at 91 total deaths with an average rate of 6.4 per 100,000 per year. Those death rates fell rapidly after FY2004, the first full year when ICE was operational, from 11.9 per 100,000 detainees to 2.9 per 100,000 detainees in 2008. The death rate rose 26 percent during the first year of the Obama Administration in 2009, then started falling again the next year with an average annual death rate of 2.3 per 100,000 detainees during his entire presidency. We only have data for three years of the Trump administration where the annual death rate is 2.4 per 100,000 detainees, which is well below the 2.7 per 100,000 death rate during the first three years of the Obama administration.

Figure 1

ICE Detentions and Deaths in Detention Facilities

Sources: ICE and Author’s Calculations.

This excellent study of death rates in ICE detention gives three reasons for why death rates fell so much during the Bush years and remained low thereafter. The first is that the length of time that immigrants spent in detention fell, which means there was less opportunity for each individual to die even though more were in detention. The second was that ICE increasingly relied on Secure Communities and local law enforcement to first arrest illegal immigrants and then transfer them to ICE. Local law enforcement agencies typically provided any healthcare that the immigrants needed before being transferred to ICE or, tragically, many of them died in local law enforcement custody. The third is that ICE medical policies and practices improved over time.

Even though the number of people in ICE detention is increasing, the chance of dying in immigration detention is on a generally downward long-term trend that has been stable for the last several years.