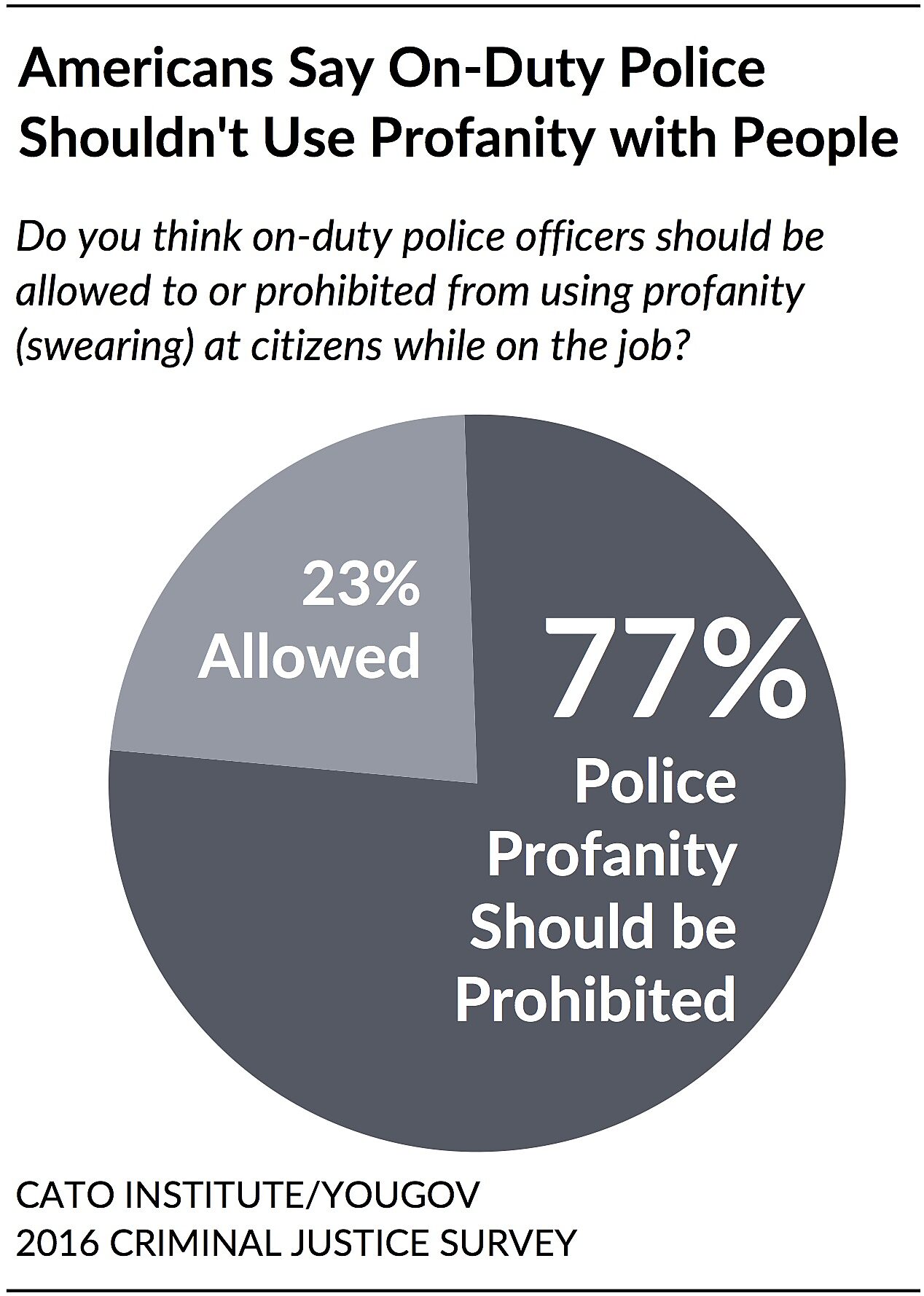

Nearly 20% of Americans report a police officer having used profanity with them. Yet, an overwhelming majority—77%—of Americans say police should be prohibited from using profanity or swearing at citizens while on the job. Twenty-three percent (23%) say police ought to be allowed to swear at citizens while on duty, according to a newly released Cato Institute/YouGov survey.

Find the full public opinion report here.

Opposition to police profanity reaches rare bi-partisan consensus—77% of Democrats and 75% of Republicans agree that police shouldn’t swear at people. Americans of virtually every demographic group identified strongly oppose allowing police use such language, including 77% of whites, 82% of blacks, and 72% of Latinos.

Why might police profanity matter? First, police image matters, and profanity could make police appear unprofessional, undisciplined, or “lacking self-control” as one research subject put it. Research experiments have shown that police using profanity are perceived as less fair and impartial. Further, police using profanity at the same time as using physical force with a person may cause people to view the force as excessive. Given that personal encounters with police may be the strongest driver of attitudes toward law enforcement, one bad experience with police profanity may significantly harm a person’s willingness to trust and cooperate with police.

Second, some have argued that officers using profanity can “set someone off” and unnecessarily escalate confrontations with people leading to more force being used than was otherwise needed. Third, some contend police using such language can harm officers during court proceedings by appearing less sympathetic in front of the judge and jury.

Experience with Profanity

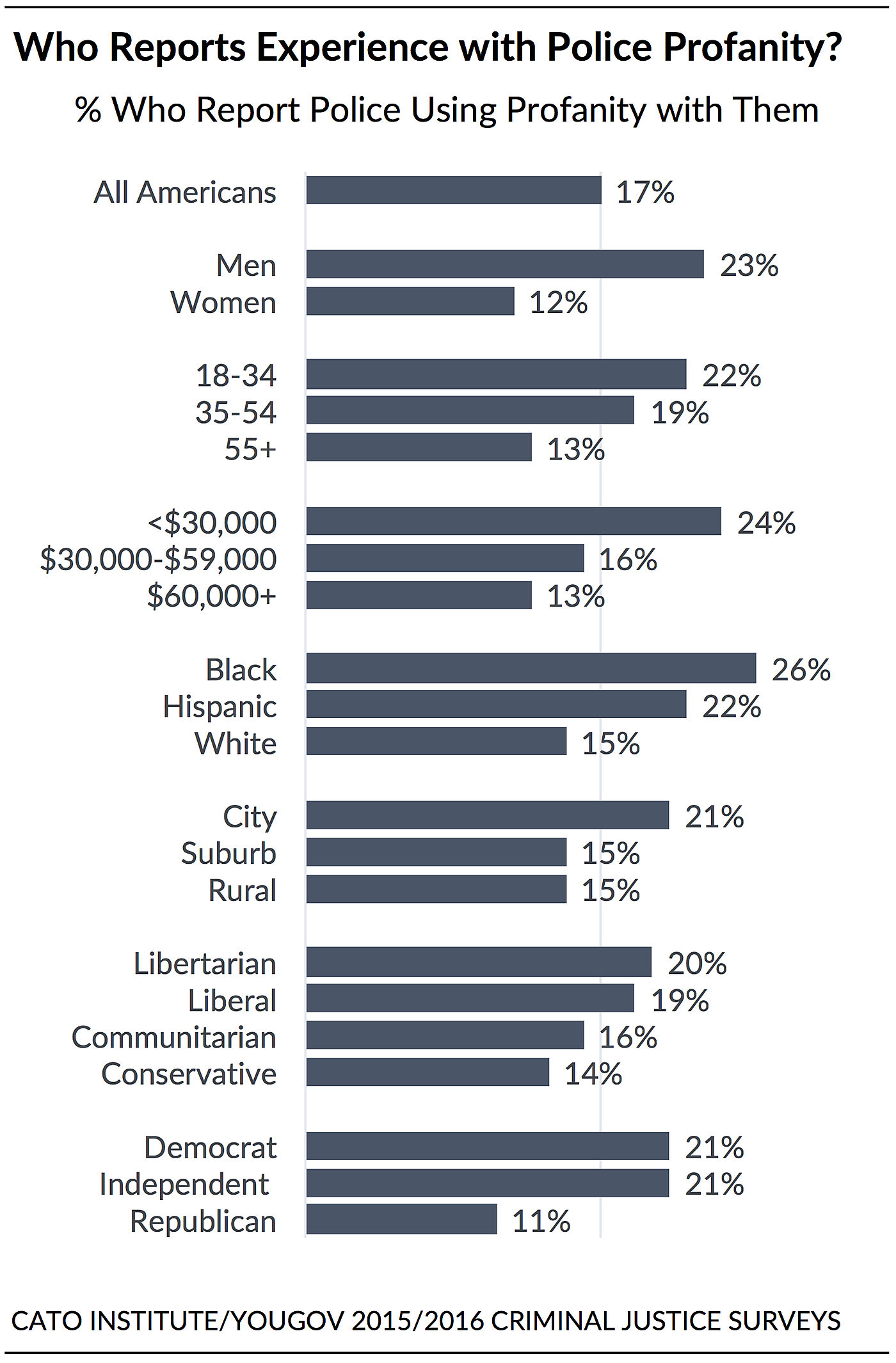

Some groups are more likely than others to report having an experience where police used profanity or abusive language with them. I combined two Cato Institute/YouGov surveys that asked this same question (which offers greater precision among small groups) and found: men (23%) are about twice as likely as women (12%), millennials (22%) about twice as likely as those over 55 (13%), households making less than $30,000 a year (24%) are about twice as likely as those making over $60,000 (13%), and blacks (26%) are about twice as likely as whites (15%) to report a police officer using profanity or abusive language with them.

Libertarians (20%) and liberals (19%) are also slightly more likely than conservatives (14%) to say an officer swore at them. Democrats (21%) and independents (21%) each are about twice as likely as Republicans (11%) to say a police officer used abusive language with them.

In sum, younger people, men, African Americans and Latinos, people living in cities, and individuals who are lower income are more likely to report having had this negative experience with the police. The ideological differences also suggest that dispositions toward authority may also impact the likelihood one encounters police profanity.

Indeed our research finds that individuals with little respect for authority figures are about three times as likely to say police have sworn at them, compared to those with high respect for authority (27% vs. 9%). However, this pattern primarily holds among white Americans. African Americans and Hispanic Americans are about equally likely to experience police profanity regardless of their dispositions toward authority figures.

In sum, although about 1 in 5 report experience with police profanity, and some groups disproportionately so, Americans overwhelmingly oppose police using profanity with people. Furthermore, research suggests policing guidelines prohibiting use of such language is wise and could enhance police-community relations.

For public opinion analysis sign up here to receive Cato’s upcoming digest of Public Opinion Insights and public opinion studies. You can follow Emily Ekins on twitter @emilyekins.

The Cato Institute/YouGov national survey of 2,000 adults was conducted June 6–22, 2016 using a sample drawn from YouGov’s online panel, which is designed to be representative of the U.S. population. YouGov uses a method called sample matching, and restrictions are put in place to ensure that only the people selected and contacted by YouGov are allowed to participate. The margin of sampling error for all respondents is +/-3.19 percentage points. The full report can be found here, topline results can be found here, and full methodological details can be found here.