The Trump administration has given notice of its intent to expand a current rule denying certain immigration applications to “public charges”—that is, people who are likely to rely on the government for their support. “The primary benefit of the proposed rule would be to help ensure that aliens … are self-sufficient,” the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) writes in a leaked version of the draft regulation. This intention coheres with Cato proposals to move immigrants (and everyone else) off government support, but the rule itself has serious problems that will have a net negative effect on government budgets.

Since 1891, federal immigration law has denied visas or status to foreigners deemed “likely to become a public charge” in the United States. The likely public charge law does not directly prevent immigrants from legally receiving welfare. Rather, it prevents them from receiving legal status in the United States if a government bureaucrat predicts that they could end up at some point in the future depending on welfare that the law allows them to receive. This draft rule would alter the procedures governing how DHS bureaucrats make these likely public charge predictions. It would apply to anyone in the United States applying to adjust or extend their status in the country or those seeking to enter the country for the first time.

DHS’s current guidance from 1999 defines public charge to mean “primarily dependent” on welfare, as demonstrated with the receipt of certain cash welfare programs. This new rule would redefine the term to mean receipt of any government assistance, including refundable tax credits, in any amount greater than 3 percent of the poverty line—$1 per day for a single person or 50 cents per day per person for a family of four, respectively, over the course of any year of their lives. In addition, it counts the use of public benefits by U.S. citizens—spouses, children, or parents—who depend on the immigrant. To predict future use, the rule requires adjudicators to consider a list of seven factors and at least 19 pieces of evidence.

Brief Overview of the Draft Rule’s Problems

The new rule has seven particularly serious problems.

First, its public charge definition of a $1 per day is overbroad. Public charge has always meant a level of support substantially higher than $1 per day (not to mention 50 cents for families). Because the large majority of immigrants have net positive lifetime effects on government budgets, keeping out immigrants based on such a low level of predicted support makes little fiscal sense. It will inevitably end up excluding many immigrants who will contribute to the U.S. Treasury and economy. DHS should narrow its redefinition to “significantly dependent” on public benefits—cash or otherwise.

Second, DHS’s standard of a $1 per day entirely ignores the degree to which immigrants support themselves. Historically, “public charge” has always had two elements: 1) receipt of benefits and 2) inability to support oneself apart from the support. Yet DHS defines public charge as an absolute amount of benefits—$1/ per day—which could easily account for less than a percent of a person’s income. This outcome ignores the history of the law and lacks fiscal sense because it fails to consider the tax revenue and economic growth foreigners who work create. DHS should assess “significant dependence” based on the amount of benefits relative to the person’s expected income—at least 20 percent of the person’s annual income.

Third, DHS cannot justify counting welfare use by U.S. citizens in the immigrant’s household against applicants. Not only would the U.S. citizens receive these benefits even if the immigrant receives no legal status, but also denying legal status to an immigrant with U.S. citizen dependents would likely increase the citizens’ use of public benefits. DHS should only consider benefits used by dependents if they are noncitizens that they have brought with them to the United States.

Fourth, the rule fails to define what DHS means by “likely” to use benefits. Likely implies a level of certainty appreciably above 50:50, but DHS never clarifies this, leaving it up to bureaucrats to decide the threshold on a case-by-case basis. This will lead to inconsistent adjudications and denials to people who should receive approvals. These false positives could result in billions of dollars in lost output and federal revenue without offsetting benefits. A redrafted rule should define the meaning of the word “likely” in accordance with its accepted meaning—a threshold of 70 percent probability of use—giving clarity to applicants and adjudicators.

Fifth, the rule’s complex weighting system for determining likelihood to use benefits is entirely arbitrary. Bureaucrats would determine how to weight the factors—such as age, health, and income—on an ad hoc basis. The process is equivalent to a “merit-based” points system where applicants do not know the point values, and bureaucrats make them up as they go. DHS should use careful statistical analysis to create a factor model to estimate the probability of use precisely. This model would allow immigrants to know whether they qualify in advance of applying.

Sixth, the administration has failed to harmonize DHS’s new rule with State Department’s separate public charge regulations. This means that immigrants who have received a visa abroad, which authorizes travel to the United States, could be evaluated against a completely different standard when they reach a port of entry or, later, when they file additional immigration applications inside the United States. Such discord would create chaos in the legal immigration system. DHS should defer to State Department public charge determinations unless a material change has occurred since State Department approved the immigrant.

Seventh, DHS failed to estimate the major costs of the rule. They only consider the costs associated with filing forms, not with excluding immigrants from the country or separating U.S. citizens from their families. DHS needs to calculate the full costs of the rule. To do so, it needs to estimate the number of immigrants the rule would exclude and estimate the direct and indirect effects of these exclusions on tax receipts and economic growth.

Without these reforms, this rule would exclude far more contributors to the United States than public charges. If Congress wants to prevent immigrants from using any welfare at all, it should amend the law to reflect that goal. Until then, DHS should return to the drawing board and craft a better rule.

What the New Regulations Would Change

U.S. law prohibits any foreigner who is “likely at any time to become a public charge” from receiving a visa or status (8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4)(A)) and requires deportation of those who become a public charge within five years except from “causes affirmatively shown to have arisen since entry” (8 U.S.C. 1227(a)(5)(A)).” These provisions fail to define any of their terms, but the “likely public charge” assessment must consider several factors: age, health, family status, assets, resources, financial status, and education or skills (8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4)(B)). They may also consider the sponsor’s affidavit pledging to support the applicant at 125 percent of the poverty line. If adjudicators do find them to be a “public charge,” they can request that the applicant post a bond to overcome the determination (8 U.S.C. 1183) that the immigrant forfeits if they become a public charge.

DHS’s current guidance came from an Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) decision in 1999 to define public charge for the first time, stating that it meant any alien “primarily dependent on the Government for subsistence, as demonstrated by either the receipt of public cash assistance for income maintenance or institutionalization for long-term care at Government expense” (INS, p. 2). It only considers likelihood to use cash assistance—Supplemental Security Income, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, and state and local cash assistance—or “long-term institutionalization” (INS, p. 7). It excluded Medicaid, Food Stamps, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, health insurance subsidies, housing benefits, child care services, job training, transportation benefits, refundable tax credits, and similar state or local programs, and it maintained a distinction between “earned” cash benefits like Social Security or unemployment insurance from unearned ones (INS, p. 7).

The likely receipt of even these limited benefits will not necessarily result in a public charge determination (INS, p. 7). Rather, the adjudicator must account for the “totality of the circumstances,” considering the factors listed in the statute. The State Department adopted the same definition and similar guidance for issuing visas abroad (which was updated in January 2018). The current DHS guidance fails to give applicants a concrete understanding of when they would be deemed a public charge, but because the definition of public charge is so limited, it creates very little disruption. Barely a half of a percent of immigrant visa applicants—and virtually no temporary visa applicants—received such a public charge visa refusal in 2017, and two thirds of those overcame the determination through additional evidence or bonds.

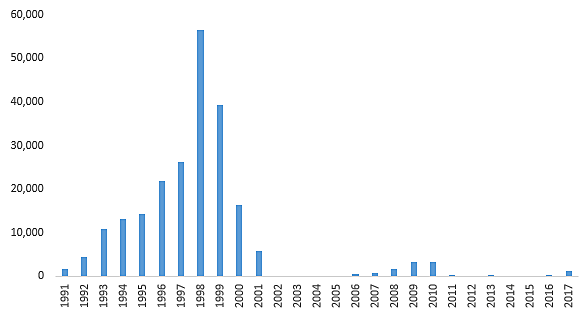

Relying on the State Department’s older guidance that considered noncash benefits but did not provide a definition of “public charge” or “likely to become,” consular officers refused 204,733 immigrant visas on public charge grounds from 1991 to 2000, ramping up steadily year after year until the 1999 guidance (Figure below). The State Department also rejected 35,290 nonimmigrant visas. During this time, public charge refusals represented nearly a quarter of all immigrant visa denials and accounted for nearly all denials based on a specific ground of refusal as opposed to the general ground “Applications Do Not Comply With the Law.”

From 2001 to 2017, the State Department refused just 8,176 immigrant visas on public charge grounds—7 percent of total immigrant visa refusals—and 11,877 nonimmigrant visas—0.4 percent of the total. Unfortunately, the trends before 1991 are unknown.

Figure 1: Public Charge Visa Refusals by State Department Consular Officers, 1991–2017*

Source: U.S. Department of State (1991–1999, 2000–2017)

*Note that years with no refusals actually had “negative” refusals, meaning that refusals in prior years were overturned

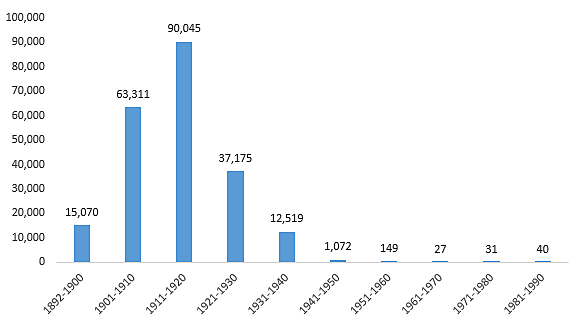

To put the 204,000 State Department visa refusals in context, INS denied entry to only slightly more than that number in its entire history from 1892 to 1990 (219,439). INS’s public charge denials fell so low that it stopped publishing the figures after 1990.

Figure 2: Immigration and Naturalization Service’s Public Charge Exclusions at Ports of Entry, 1892–1990

Source: Immigration and Naturalization Service

DHS’s new draft regulations would repeal the “primarily dependent” guidance and redefine public charge to mean “any government assistance in the form of cash, checks or other forms of money transfers, or instrument and non-cash government assistance in the form of aid, services, or other relief, that is means-tested or intended to help the individual meet basic living requirements such as housing, food, utilities, or medical care” (pp. 204–205). It would also end the cash-noncash distinction and incorporate a list of 14 benefit types, including Medicaid, Food Stamps, Child Health Insurance Program, and refundable tax credits like the Earned Income Tax Credit (pp. 210–11). Italics in Table 1 indicate changes from current law. It would exclude “earned” benefits like Social Security, public education, government loans, in-state tuition, disability benefits, and Medicare unless a government covered the premiums.

Table 1: List of Public Benefits Included or Excluded from Public Charge Consideration under DHS Draft Rule

| Public benefits include | Public benefits exclude | ||

|

1 |

Supplemental Security Income |

1 |

Social Security (OASD) |

|

2 |

Temporary Assistance to Needy Families |

2 |

Veteran’s benefits |

|

3 |

State cash benefit programs |

3 |

Unemployment insurance |

|

4 |

Other Federal benefits for purposes of maintaining the applicant’s income |

4 |

Medicare benefits, unless the premiums are partially or fully paid by a government agency |

|

5 |

Nonemergency Medicaid |

5 |

State disability insurance |

|

6 |

Subsidized health insurance |

6 |

Government loans that require repayment |

|

7 |

SNAP (Food Stamps) |

7 |

In-state college tuition |

|

8 |

Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) |

8 |

Student loans |

|

9 |

Child Health Insurance Program |

9 |

Public benefits received where the total annual value in any 1 year does not exceed 3 percent of the total Federal Poverty Guidelines |

|

10 |

Housing assistance |

10 |

Elementary and secondary public education |

|

11 |

Means-tested energy benefits |

11 |

Benefits under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act |

|

12 |

Institutionalization at government expense |

12 |

Non-refundable tax credits, and refundable tax credits that are not means-tested |

|

13 |

EITC (and similar refundable tax credits) | ||

|

14 |

Other similar benefits |

Source: Department of Homeland Security.

Note: italics = change from current law.

The proposed rule would also not consider de minimis amounts of public benefits of less than 3 percent of the federal poverty line, $364 a year for a single person or $753 for a family of four—the equivalent of $1 per day per person or 50 cents per day per person, respectively (pp. 211–12). It would consider benefits received by dependents, including citizens, of the immigrant (pp. 69, 74–76). The draft rule change would only take into account newly classified benefits if the applicant received them after the date on which the new regulations are finalized (p. 111). This would give current recipients time to transition to self-sufficiency.

In addition, if an adjudicator determines an applicant to be a likely public charge, they can allow them to post a public charge bond—currently a procedure rarely used. The applicant would pay an amount commensurate with their level of risk but not less than $10,000 (pp. 115–17) and be allowed to adjust status or enter the country. This process would only be available, however, to those without a highest level of risk, based on factors described below (see Tables 2 and 3 at the end). The bond amounts would be based on the average 5‑year benefit receipt level for persons using public benefits based on household size.

Moreover, the new rule would affect immigrants only when applying to enter, extend, or change their status in the United States (p. 1). In the leaked draft, the sections related to deportability are left blank “to be inserted” (pp. 219–220). Even if the change did apply to current residents, it is unlikely to result in many deportations. Under current law, if a resident can show that the causes of their indigence arose after their arrival, or that they became a public charge more than 5 years after entry, they cannot be deported (8 U.S.C. 1227(a)(5)(A). At the same time, case law requires government authorities to request repayment within 5 years of the person’s entry, a legal obligation must exist to repay, and the immigrant must refuse to repay (see Matter of B—, 3 I. & N. Dec. 323 (BIA 1948)).

Problems with the DHS Public Charge Rule

1. DHS defines “public charge” much too broadly

The average immigrant is a lifetime net fiscal contributor. The National Academy of Sciences (NAS) recently produced a number of estimates on the direct fiscal effects of immigration (p. 349, Table 8–14), and the average of those estimates indicate that a recent immigrant to the United States will contribute to all levels of government, in net present value terms, $150,000 more in taxes than they receive in benefits over their lifetime. That makes it critical that the definition of “public charge” is not overbroad, excluding people who would be net fiscal contributors. Unfortunately, DHS’s definition is overbroad.

DHS labels as a “public charge” any immigrant who it expects to receive, as a single person, $1 per day or more in public benefits (pp. 211–12). For a family of four, it sets the level at 50 cents per day per person. This definition fails to accord with the plain meaning or historical understanding of “public charge”—or ward of the state—which has always implied a significant degree of support, not any support at all. Nineteenth century authorities use the phrase in connection to vagrants, beggars, indigents, or paupers. The Immigration Act of 1891 explicitly equated people likely to become public charges with paupers. Each of these words denotes a severe level of impoverishment.

The legislative history reinforces this impression. In the 1820s, New York and Massachusetts passed laws to require shipmasters to pay a bond to indemnify the city against costs associated with passengers who later became “chargeable as paupers” to the city. The bonds were forfeit if the individual entered an almshouse within a few years of entry, meaning that almshouse residency was the effective definition of public charge. The Supreme Court’s 1875 decision to overturn these state laws as unconstitutional led directly to the 1882 passage of the federal law that excluded immigrants “chargeable as paupers,” later amended to keep out those “likely to become a public charge” in 1891. Courts subsequently read this phrase “to exclude persons who were likely to become occupants of almshouses for want of means with which to support themselves in the future” (Howe v. Savitsky (1917)).

Unlike INS’s 1999 guidance, DHS makes absolutely no attempt to tie its new rule change to this history. Indeed, all they can offer as justification is the 1922 case of Ex parte Kichmiriantz in which a California District Court read the statute to mean “money charge on, or an expense to, the public for support and care” of an immigrant. Yet this case involved a young man admitted to an insane asylum for permanent year-round care. DHS cannot extrapolate the phrase “an expense to the public” in the context of this case into any expense at all. Far from undertaking a rigorous analysis of the phrase, the judge was simply noting that given the fact that the man had not imposed any expense to the public because his parents had covered his bills, he could not possibly be a public charge. DHS reverses the judge’s meaning. Nothing in the legislative history or judicial record endorses such a broad rule.

Excluding people based on such a low level of welfare consumption makes no fiscal sense either. According to NAS, the vast majority of immigrants are fiscal contributors (p. 349). The DHS rule implies that America’s fiscal outlook would improve if most Americans, who at some point live in a household using benefits, set out for other lands. Far from protecting U.S. taxpayers, such an exodus would shrink the economy and tax revenues with it. This absurd conclusion demonstrates the importance of a narrowly targeted rule.

DHS could, however, reasonably update its public charge definition. By excluding noncash benefits of any kind, the current guidance implies that someone could not become primarily dependent on the government through their use alone or in combination with other assistance. This is incorrect. The statute could justify a broader definition, such as “significantly dependent,” that also considered noncash benefits.

2. DHS defines “public charge” without regard to ability to support themselves

As the history of public charge shows, the phrase has always had two aspects: 1) receipt of significant government assistance and 2) inability to support oneself apart from that assistance. That is why historical sources identify public charges with paupers and other destitute individuals. Howe v. Savitsky (1917) emphasized that public charges entered almshouses “for want of means with which to support themselves in the future.” In the original understanding, public charge was not just about the willingness of the person to use benefits, but also the perceived moral necessity of the government giving them benefits. The government had to take “charge” of the person to prevent their starvation or total destitution.

For this reason, current DHS guidance defines public charge relative to the income of the applicant, “primarily dependent” on government assistance (i.e. 51 percent of a person’s income). According to DHS, it “does not believe that an alien must be 50 percent or more dependent on the government to be considered a public charge” (p. 42). This objection is reasonable, but rather than reducing the standard to 51 percent to 30 percent, 20 percent, or 10 percent, of a person’s income, they drop the relative standard entirely and adopt an inflexible absolute threshold of 3 percent of the poverty line: a dollar per day (or less in the case of families). Even a person in poverty could be expected to be more than 95 percent self-sufficient, yet receive a public charge determination. People with higher incomes could be more than 99 percent self-sufficient, and yet receive public charge denials.

In 1906, the House of Representatives considered a bill that would have required all male immigrants to present $25 to avoid a public charge determination. In 1907, nominal per capita GDP was $392.81, so the proposed requirement was 6 percent of per capita GDP. In 2017, 6 percent of per capita GDP was about $3,100. In 1906, however, members of Congress saw the $25 test as much more restrictive than current law, meaning that because this legislation never became law, it would be difficult to justify an interpretation more restrictive than this standard. Beyond the failure to accord with the statute, an absolute amount of benefits receipt is fiscally senseless because it ignores the tax revenue and economic growth created from productive foreign workers.

Public charge implies a degree of support where the person would have significant difficulty surviving without the government assistance. As suggested above, a reasonable definition of public charge would require the person to be “significantly dependent” on the government. DHS should define significant dependence relative to the person’s income. DHS can reasonably argue that the current 50 percent threshold is too high. At the same time, if 90 percent of an applicant’s income is expected to come from private sources, they would clearly not be a public charge, as they are nearly self-sufficient already—20 percent of annual income seems like the lowest reasonable definition.

3. DHS counts benefits received by U.S. citizen family against immigrants

DHS will consider public benefits that the U.S. citizen children or spouses in the immigrants’ household may receive in the future if they are the immigrants’ dependents (pp. 69, 74–76). In other words, the one dollar or 50 cents per day standard of support may not even be intended for the immigrant themselves, but rather U.S.-born citizens. On numerous occasions, Cato has criticized this household-centric methodology of assessing the fiscal effects of immigration. Counting the fiscal effects of U.S.-born spouses for or against immigrants is unjustifiable, and while the effects of their descendants are worthy of consideration, considering them only when they live in the household with the immigrant leads to absurd conclusions, like all children are fiscal drains (true, but only as children).

DHS should expect immigrants to support those noncitizen dependents that they bring with them. But even without legal status for the immigrant, U.S. citizens in their household would either 1) receive the same benefits or 2) receive even more benefits if the parent or spouse on whom they depend is refused status in the country. In other words, banning immigrants based on the projected future use of their citizen dependents could actually have negative fiscal value by removing the means of support for certain citizens.

DHS could claim that but for the immigrant, the U.S.-born children would not exist. As a theoretical matter, it is unclear how DHS could justify this counterfactual. Without the immigrant, their spouse may have married someone else and had just as many children. Regardless, the fact is that these children do already exist at the time of application. Counting their receipt of benefits for public charge purposes would not result in the children becoming ineligible for those benefits. DHS’s methodology only results in the denial of status to the breadwinner, which would likely make their children or spouse needier. DHS should only consider the receipt of benefits of the noncitizen dependents of the applicant.

4. DHS fails to define “likely” to become a public charge

Because current guidance only considers cash benefits—and just 1 in 56 noncitizens currently use cash benefits (p. 51)—the prior probability of an applicant becoming a public charge under its definition is low. Only extraordinary circumstances result in denials on this ground. By contrast, 1 in 4 noncitizens use noncash benefits (p. 51). This raises the prior probability considerably and so requires more carefully considering how the prediction is made. Unfortunately, DHS failed to clarify the key word “likely,” leaving it up adjudicators to determine the probability threshold for refusal on a case-by-case basis.

Without stipulating an acceptable rate of false positives—people erroneously excluded—DHS leaves it open to individual adjudicators to develop their own standards. This will sow chaos in the immigration system as applicants will have no way to know how their application will be processed. This type of uncertainty results in fewer applicants overall—another cost of the rule. Indeed, it was partly for this reason that INS issued its guidance in 1999.

In plain language, “likely” means, per Merriam-Webster, “having a high probability of occurring or being true” or “very probable.” These definitions imply a probability appreciably higher than 50:50. According to a CIA analysis, the median CIA analyst considers “likely” to refer to a roughly 70 percent chance of occurrence. The 30 or more percent who are deemed a likely public charge when, in fact, they would not become a public charge if granted the ability to live in the United States legally is a major cost of the rule that DHS fails entirely to reckon with. Congress did not write a statute that allows DHS to exclude anyone who has a “significant possibility” of becoming a public charge. They specified “likely.” DHS should clarify the meaning of “likely” as a 70 percent probability of future benefits use.

5. DHS’s process for determining likelihood will mislabel applicants as public charges

The draft rule creates a nontransparent weighting system to identify whether someone is likely to be a public charge. Like the underlying statute (8 U.S.C. 1182(a)(4)(B)), the rule calls for adjudicators to take into account seven primary factors—age, health, family status, assets, resources, financial status, and education or skills—and 19 types of evidence (pp. 205–209, see Table 2). It also adds four heavily weighted negative factors—inability to show employment history or prospect of employment, past public benefits use, a medical condition without unsubsidized health insurance, and an earlier public charge determination—and a heavily weighted positive factor—being able to support oneself and dependents at 250 percent of the poverty line (Table 3).

DHS uses the above factors to create tables showing welfare participation rates among various subpopulations of foreign-born residents, noting purported correlations between a certain factor and welfare use (pp. 51–105). All of these tables are based on all foreign-born residents rather than subgroups that must pass a public charge test. Even still, none of the subpopulations had, according to DHS’s own tables, benefits use rates above 50 percent. Even a minority of all foreign-born residents with incomes below 125 percent of the poverty line received public benefits of any kind in 2013 (p. 105). In other words, none of DHS’s tables by themselves provide evidence in favor of a likely public charge determination based on its factors.

DHS does state that it will take into account all of the factors, considering the “totality of circumstances” (p. 209). “If the negative factors and circumstances outweigh the positive factors and circumstances,” it writes (p. 56), “then DHS would conclude that the applicant is likely to become a public charge.” This weighting mechanism only adds to the confusion. It replaces a simple checklist with an infinitely complex factor model. If none of the factors separately indicates a likely public charge determination, DHS would need to show that the combination of any two factors increase the likelihood of public benefits use and by how much. To do this, they would need to use statistical analysis to identify which factors actually matter.

Rather than clarifying its weighting system, DHS explicitly notes that it will adopt different weights on a case-by-case basis, stating that the “weight given [by an adjudicator] to an individual factor would depend on the particular facts and circumstances of each case” (p. 55). DHS states that “multiple factors operating together may be weighted more heavily” (p. 55). Yet DHS fails to validate any of its conclusions with statistical analysis. As a result, many of its factors could be measuring the same underlying issue.

DHS fails to appreciate this flaw in its system. It notes purported correlations between welfare participation and education (p. 80) as well as income (p. 102). Further, it claims to show “relationships” between public benefits use and age (p. 58), family size (p. 72), English language proficiency (p. 89), and poor health (p. 99). Other discussions imply correlations between public benefits use and educational certificates or licenses (p. 87), employment (p. 95), past benefits use (p. 74), income of sponsor (p. 94), and receipt of a fee waiver for an immigration application (p. 76).

Yet it is clear that these factors are all related. Benefits availability is based on income thresholds. Employment and age are correlated. English language proficiency is related to education level, and so on. DHS simply has not demonstrated which factors matter and which do not. Thus, an applicant could receive negative weights for four or five factors that have no effect, while the one that does have an effect is “outweighed” in DHS’s analysis.

One factor deserves special attention. DHS gives little weight to the sponsorship of immigrants and to sponsors affidavits of support, writing that “DHS expects that a sponsor’s signed agreement would not be an outcome-determinative factor in most cases” because “DHS does not believe that an affidavit of support guarantees that the alien will not use or receive public benefits” (p. 94).

In support of this latter proposition, it cites a 2009 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report finding that 11 percent of sponsored immigrants applied for TANF, Medicaid, or SNAP during the course of 2007 (p. 93). Yet this same report found that “applicants often withdraw their applications” when they discover that the sponsor may have to repay benefits or that their sponsor’s income level may make them ineligible (GAO, pp. 10–11). While national benefit use data for sponsored noncitizens were unavailable, less than 0.05 percent of TANF, Medicaid, or SNAP recipients in Florida were sponsored noncitizens (GAO, p. 13).

This faulty weighting system causes four problems. First, it will result in denials of applicants who should receive approvals. Second, it will lead to denials of applications from people who should never have applied. Third, it will lead to inconsistency between adjudicators with each adopting different standards. Fourth, the inconsistency and uncertainty will reduce applications from people who should apply. All of these mechanisms will injure, rather than protect, the public purse. DHS should use data to create a statistical model that provides precise and objective predictions about future use.

6. DHS’s rules conflict with State Department’s public charge guidance

DHS’s rule applies only to immigrants (i.e. permanent residents) or temporary visitors, workers, and students (i.e. nonimmigrants) seeking admission at ports of entry or adjusting or extending status inside the United States (p. 1). The State Department handles issuing visas to foreign nationals abroad. In order to obtain a visa, immigrants must also prove to State Department consular officers that they are not likely to become a public charge. Visas allow immigrants to board planes and ask DHS immigration officers to enter the United States. Yet DHS’s new rule substantially conflicts with State Department’s separate public charge guidance, meaning that immigrants could end up receiving approvals from State abroad only to receive denials from DHS in the United States.

When the State Department updated its public charge guidance in January 2018, it retained the old “primarily dependent” definition of public charge that excludes dependence on noncash benefits. Its January changes reasonably allow consular officers to consider noncash benefits as one reason to believe that a person may become dependent on cash assistance. They also overturn a presumption that an affidavit of support by itself is sufficient to show non-likelihood, requiring consular officers to consider whether the sponsor is themselves already on public benefits. But even with these updates, State’s guidance is much less onerous than DHS’s proposed rules (as well as more transparent), resulting a dramatic disconnect between policy abroad and policy in the United States.

State could again update its public charge guidance to harmonize it with DHS’s changes, but considering it just updated it in January, we have reason to doubt this. According to DHS, State “would continue to review affidavits of support and screen aliens for public charge inadmissibility in accordance with its regulations and instructions prior to the alien undergoing inspection and applying for admission at a pre-inspection location or port-of-entry” (pp. 36–37). DHS does not explain how the agency would handle any potential conflict. Regardless whether State updates its guidance again, DHS should specifically clarify that it will defer to State Department public charge determinations if State reviews the immigrant before DHS, unless their situation has significantly changed.

7. DHS failed to consider most of the costs of its public charge rule.

DHS’s cost-benefit analysis stretches for 36 pages, but only considers the costs of its new immigration application forms (pp. 146–182). It specifically states that it “was not able to estimate potential lost productivity, early death, or increased disability insurance claims as a result of this proposed rule” (p. 129). In addition, here are costs that DHS has failed to consider:

- The number of immigrants excluded under this rule as well as the number of U.S. citizens denied the ability to hire foreign employees, reunite with their spouses, children, parents, or siblings, or otherwise engage with foreign persons.

- Lost economic growth and tax revenue due to excluding more immigrants and temporary visitors than under current law.

- Lost economic growth and tax revenue due to excluding immigrants who use only minor benefits (see #1 above).

- Benefits use increases by U.S. citizens due to denying legal status to immigrants with U.S. citizen dependents (#2 above).

- Lost economic growth and tax revenue due to excluding immigrants who are not likely to become a public charge (#3–4 above).

- Lost economic growth and tax revenue due to immigrants and nonimmigrants refusing to apply in the face of greater uncertainty and higher fees (#3–5).

DHS did not consider broader economic and fiscal effects of its rule because it claims that “there is a lack of academic literature or economic research examining the link between immigration and public benefits,” (p. 129) citing chapter 9 of Harvard economist George Borjas’s non-academic book, We Wanted Workers (2016). Yet nowhere in the cited chapter does Borjas claim to have reached this conclusion. Indeed, he cites the National Academy of Science’s 1997 and 2016 reports on the fiscal effects of immigration, which found short-term net costs and long-term net benefits to all levels of government. These reports in turn cite other studies. Alex Nowrasteh’s 2014 review of the academic literature on the fiscal impact of immigration has more nine pages of academic references.

DHS further states that it “is also difficult to determine whether immigrants are net contributors or net users of government-supported public assistance programs since much of the answer depend on the data source, how the data are used, and what assumptions are made for analysis” (p. 129). The difficulty cannot be doubted, but academics have already performed the most difficult tasks, identifying the assumptions that matter and how they effect the results, and DHS is under a legal obligation to undertake such an analysis. The unwillingness to make assumptions simply defaults to an assumption of zero cost. DHS is effectively telling the public that if the costs are infinite, the rule is still worth it.

Conclusion

The rule would not prevent legal immigrants from accessing welfare if the law allows them to obtain it, setting up a strange dichotomy between our rules at entry and our rules after entry. Under current law, the administration generally cannot prevent immigrants from using welfare in such cases, so no matter how the administration ends up reforming the public charge determinations, Congress should amend the law to limit government benefits only to citizens. The private sector can—and already is—aiding immigrants when they fall on hard times or need help to get ahead, and the evidence indicates that similar restrictions enacted in 1996 had no major effects on immigrant poverty.

A strict no-welfare rule would further protect U.S. taxpayers, allow for higher levels of immigration, provide an incentive for immigrants to assimilate and naturalize, and avoid the necessity—as under this new rule—of turning bureaucrats into soothsayers.

Table 2: Factors for Public Charge Determinations under DHS Rule

| Factors | |

| I | The alien’s age |

|

1 |

between 18 and 61 |

| II | The alien’s health. |

|

2 |

A diagnosis of a medical condition by a civil surgeon or panel physician; |

|

3 |

Evidence of non-subsidized health insurance |

|

4 |

Evidence of assets and resources |

| III | The alien’s family status |

|

5 |

being a dependent or having dependent(s) makes it more or less likely that the alien will become a public charge. |

| IV | The alien’s education and skills. |

|

6 |

a history of employment |

|

7 |

a high school degree or higher education |

|

8 |

any occupational skills, certifications, or licenses |

|

9 |

proficient in English or another language as relevant to working fulltime |

| V | The alien’s assets and resources |

|

10 |

the alien can support him or herself and any dependents, at the level of at least 125 percent of Federal Poverty Guidelines |

|

11 |

The alien’s annual gross income |

|

12 |

support to the alien from another person |

|

13 |

The alien’s cash assets and resources, including as reflected in checking and savings account statements |

|

14 |

The alien’s non-cash assets and resources that can be converted into cash within 12 months |

| VI | The alien’s financial status |

|

15 |

Whether the alien or any dependent has sought, received, or used, or any public benefit |

|

16 |

Whether the alien has sought or has received a fee waiver for an immigration benefit |

|

17 |

The alien’s credit history and credit score |

|

18 |

Whether the alien has received or is currently receiving any subsidized health insurance |

| VII | An affidavit of support |

|

19 |

Sufficient affidavit of support must meet the sponsorship and income requirements |

Table 3: Heavily Weighted Factors for Public Charge Determinations under DHS Rule

| Heavily Weighted Negative | |

|

1 |

Non-students who are unable to demonstrate current employment, and have no employment history or no reasonable prospect of future employment |

|

2 |

Using one or more public benefits within the last 36 months |

|

3 |

Having a medical condition and being unable to show evidence of unsubsidized health insurance, the prospect of obtaining it, or other non-governmental means of paying for treatment |

|

4 |

Having previously been found inadmissible or deportable based on public charge |

| Other factors as warranted | |

| Heavily weighed positive factors | |

|

1 |

The alien has financial assets, resources, and support of at least 250 percent of the Federal Poverty Guidelines or is authorized to work and is currently employed with an annual income of at least 250 percent of the Federal Poverty Guidelines |

| Other factors as warranted |

State Department Regulations: 22 CFR 40.41

State Department Guidance: 9 FAM 302.8

DHS Regulations: N/A

DHS Guidance: 64 FR 28689