The Forgotten Depression, Jim Grant’s excellent book about the 1920–21 downturn and the recovery that followed, has generated a burst of critical commentary from persons anxious to reject the principal conclusion Grant draws from that episode. That conclusion, in brief, is that the U.S. was able to recover relatively quickly from at least one deep slump (and the ’21 slump was deep, to judge not only from price statistics but also from available if sketchy unemployment statistics) despite authorities’ refusal to resort to either fiscal or monetary stimulus. On the contrary, Grant observes, both fiscal and monetary policy were, according to today’s Keynesian-influenced understanding, more contractionary than expansionary.

I’ve no desire to plunge into the general controversy concerning what other lessons one might safely draw from the 1920–21 episode, except to point out (as many of Grant’s critics fail to do) that Grant himself resists drawing many other conclusions. He never claims, first of all, that Harding-administration-type policies might have been a dandy solution in 2008. Nor does he insist that post-2008-style expansionary fiscal and monetary policies would have made for a less satisfactory recovery had they been employed in ’21. “We can’t know what might have been,” Grant writes (p. 2) “if Wilson and Harding had intervened as presidents in of the late 20th and early 21st centuries are wont to do.” Grant merely settles for observing that “When, as 31st president, Hoover did intervene–notably, in an attempt to prevent a drop in wages–the results were unsatisfactory” (ibid.) The results of FDR’s more aggressive interference with price and wage cuts, through the NRA and AAA, were, I would add, still more so.

If there’s a foolish generalization lurking about here, or anywhere else in Grant’s book (say, for instance, a “citation of the 1921 economic recovery as somehow refuting everything we’ve learned about macroeconomics since then,” or an assertion to the effect that “If only we had let wages and prices crash in 2009, we would be in la la land right now,”) I hope someone (Paul? Barkley?) will be so kind as to point it out to me. I also hope Barkley will explain to me why, in purporting to refute Grant’s thesis, he compares what happened in 1920–21, not with what transpired in 1929–33 (which is the one episode concerning which Grant himself draws comparisons) but with what happened in various post-WWII recessions to which Grant himself never even refers.

My concern here, in any event, isn’t with the general lessons that either should or shouldn’t be drawn from the post-21 recovery, but with a particular myth concerning that recovery, namely, the myth that, contrary to what Grant and others have suggested, the Fed did in fact help out, and help out in a big way, by loosening of monetary policy.

Barkley Rosser has been particularly anxious to make hay with this claim, especially in the post (linked above) written in response to the recent Cato Book Forum over which I presided, featuring Grant’s book. (For his part Krugman settles for a mere link to Barkley’s post–this in a post implicitly accusing Grant, whose book Krugman almost certainly didn’t bother to read, of laziness!) “In 1921,” Barkley writes, “the Fed reversed course and lowered the discount rate back down to 4%. The economy then went into its rapid rebound. I note that in his remarks at Cato, at least Larry White did note this point as a caveat on all the proceedings. Bordo et al [sic] also note that both Irving Fisher and also Friedman and Schwartz pinpointed the role of the Fed in all this and declared it to have behaved very irresponsibly in the entire episode. But for Grant and Samuelson, the Fed barely even existed then.”

The claim about Fed easing having ended the 21 slump has been repeated by many others, including The Economist, which in its review of Grant’s book observes that “The Fed brought on the 1920–21 depression with high interest rates. Those rates drew in gold anew, which, along with deflation and political pressure, eventually caused the Fed to relent and lower rates. The slump and recovery were thus not the spontaneous product of the free market but of deliberate policy, much as in later recessions.” Another proponent of this view is Daniel Kuehn, who has written two articles and several blog posts countering Austrian claims about the implications of the 1920–21 episode. In a comment responding to a laudatory David Glasner post concerning his work on the subject, for example, Kuehn claims that Fed “loosening…definitely played a prominent role in the recovery” from the 1921 slump.

What, then, are the facts of the matter? One fact, or set of them, to which Barkley and Co. refer, is that the Fed banks did indeed lower their discount rates, from 7%, where they’d stood since June of 1920, to 6.5% in May 1921, and then all the way to 4.5% in November 1921. (The further reduction to 4% to which Barkley refers did not occur until June 1922.) But, as Scott Sumner has been tirelessly observing for some years now, even under an interest-rate targeting regime, a low policy rate doesn’t necessarily mean easy money. Instead, low rates can reflect slack demand for funds, and indeed tend to do just that in any slump. A Wicksellian would say that what matters isn’t where rates stand absolutely, but where they are relative to their “natural” counterparts.

But treating the discount rate as an indicator of the stance of monetary policy with reference to the 1920–21 episode is even worse than treating it so in reference to more recent experience. In recent times, you see, the relevant policy rate has been, not the Fed’s discount rate–the rate at which it extends discount-window loans–but the federal funds rate, to which, in the good old day’s before the recent recession, it assigned a target value, to be achieved using open-market operations, by means of which the supply of federal funds (that is, overnight loans of bank reserves) would be either increased or reduced sufficiently to bring the funds rate to its target level. A decision to “lower interest rates” by the Fed thus tended to imply a decision to expand the monetary base by adding to the Fed’s security holdings. Thus, although low rates didn’t necessarily mean “easy” money, a decision to target lower rates did at least tend to mean more money.

Back in the 20s, on the other hand, a lowering of the Fed’s policy rate–here, not the federal funds rate but the discount rate–might not even imply an increase in Fed lending or security purchases. In reducing its discount rate from 6.5% to 4.5%, for example, the Fed merely allowed banks possessing the requisite commercial paper to discount that paper with it at the newly reduced rates. Whether they would do so, however, depended on whether the rates in question were low, not merely compared to previous rates, but relative to market rates generally or, again, to “natural” rates. If not, the volume of discounting might not budge, and the lower rates would not imply any actual monetary expansion, except perhaps relative to the contraction that might have ensued had rates remained high.

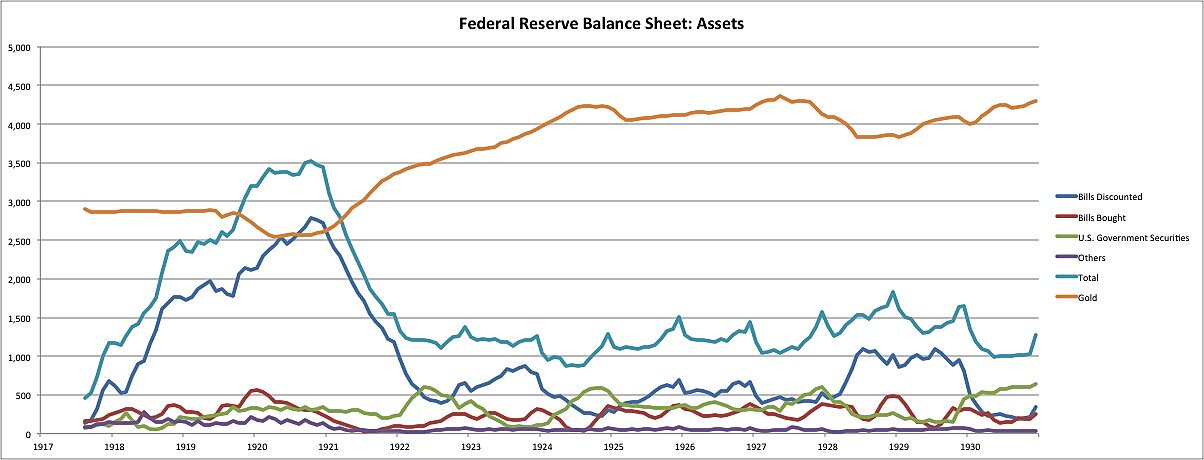

So, did the Fed, by lowering its discount rate, actually give the U.S. economy a dose of monetary stimulus? It did not, as can be readily seen by referring to the chart below, reproduced from Nathan Lewis’s New World Economics blog:

As you can see from the chart, although there was some increase in “bills discounted” in response to the Fed’s lowering of its discount rate, the increase was slight compared to the massive decline in total Fed non-gold assets since 1920. What’s more, it was more-or-less perfectly–and by implication quite intentionally–offset or “sterilized” by means of Fed sales of government securities. The Fed’s contribution to recovery, in short, consisted, not of any actual monetary stimulus, but of a mere cessation of what had been a precipitous decline in its interest-earning asset holdings.

This isn’t to say that monetary expansion played no part in the post-1921 recovery. In fact, it played a significant part. But the expansion that took place was due solely to gold inflows, which were themselves encouraged by relatively high interest rates as well as by falling prices–that is, by the normal working of the price mechanism rather than by activist Fed policy. (In the 30s as well, by the way, such recovery as took place was entirely the result not of Fed easing–or of fiscal stimulus–but of the dollar’s devaluation and subsequent gold inflows from Europe.) That gold flows (as opposed to Fed easing) contributed to the post-1921 recovery is itself a fact that Jim Grant readily acknowledges; his book’s 17th chapter is called “Gold Pours into America.”

In fine, far from having overlooked the real cause of the recovery, as his critics claim, Grant seems to have gotten it just right, whereas they all seem to have been led astray by an interest-rate red-herring.

_____________________

Postscript:

While preparing this post I was unaware of Bob Murphy’s reply to Krugman’s remarks, which is very much worth reading.