Presented at the “Peace Through Trade” Conference, World Trade Centers Association, Oslo, Norway.

In Washington, as in Europe, trade policy is fought almost exclusively on the battlefield of bread and butter. What does it mean for exports, jobs, wages, and competition? At the Center for Trade Policy Studies, we think that the evidence is clear that trade benefits the U.S. economy and American families. Expanding trade, foreign investment and competition deliver lower prices, more choice and higher incomes for consumers. Globalization has opened fantastic opportunities for American and European companies to deliver goods and services to hundreds of millions of new customers in emerging markets.

The rising flow of capital across borders has raised returns for people who save and invest while funding new investment opportunities that spread good paying jobs and technologies around the globe. I would invite you to visit our web site, www.freetrade.org, to weigh the evidence for yourself. But trade policy is also about the kind of wider world we want to live in.

During the decades of the Cold War, Republican and Democratic presidents alike in the United States advocated international trade as a necessary tool for promoting human rights and democracy abroad, and ultimately a more peaceful world. Trade expansion was seen as an instrument not only for raising living standards but also for knitting together our Cold War allies and spreading the values and blessings of freedom to a wider circle of mankind. Trade was seen, rightly, as an instrument of peace in a world that had suffered two calamites world wars and only to face another totalitarian power in the Soviet Union.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the founding of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. Sixty years ago this month, representatives from 23 countries, including Norway and the United States, met in Geneva to negotiate lower tariffs on goods within a framework of nondiscrimination and the rule of law. The participating countries understood all too clearly that the “beggar thy neighbor” protectionism of the 1930s had been an economic disaster. They also understood that economic warfare had deepened the despair and resentments that lead to World War II.

In my remarks today, I want to go beyond bread and butter to talk about how free trade is tilling the soil for democracy and human rights around the world and how the expansion of economic liberty and democracy have done more than any army of U.N. blue helmets to promote peace.

How Free Trade Tills Soil for Democracy

In one of my studies for Cato, called “Trading Tyranny for Freedom,” I examined the idea of whether free and open markets promote human rights and democracy. Political scientists since Aristotle have long noted the connection between economic development, political reform, and democracy. Increased trade and economic integration promote civil and political freedoms directly by opening a society to new technology, communications, and democratic ideas. Along with the flow of consumer and industrial goods often come books, magazines, and other media with political and social content. Foreign investment and services trade create opportunities for foreign travel and study, allowing citizens to experience first-hand the civil liberties and more representative political institutions of other nations. Economic liberalization provides a counterweight to governmental power and creates space for civil society.

The faster growth and greater wealth that accompany trade promote democracy by creating an economically independent and political aware middle class. A sizeable middle class means that more citizens can afford to be educated and take an interest in public affairs. They can afford cell phones, Internet access, and satellite TV. As citizens acquire assets and establish businesses and careers in the private sector, they prefer the continuity and evolutionary reform of a democratic system to the sharp turns and occasional revolutions of more authoritarian systems. People who are allowed to successfully manage their daily economic lives in a relatively free market come to expect and demand more freedom in the political and social realm.

Wealth by itself does not promote democracy if the wealth is controlled by the state or a small, ruling elite. That’s why a number of oil-rich countries in the Middle East and elsewhere remain politically repressive despite their relatively high per capita incomes. For wealth to cultivate the soil for democracy, it must be produced, retained, and controlled by a broad base of society, and for wealth to be created in that manner, an economy must be relatively open and free.

In my study for Cato, I found that the reality of the world broadly reflects those theoretical links between trade, free markets, and political and civil freedom.

First, I examined the broad global trends in both trade and political liberty during the past three decades. Since the early 1970s, cross-border flows of trade, investment, and currency have increased dramatically, and far faster than output itself. Trade barriers have fallen unilaterally and through multilateral and regional trade agreements in Latin America, in the former Soviet bloc nations, in East Asia, including China, and in more developed nations as well. During that same period, political and civil liberties have been spreading around the world. Thirty years ago democracies were the exception in Latin America, while today they are the rule. Many former communist states from the old Soviet Union and its empire have successfully transformed themselves into functioning democracies that protect basic civil and political freedoms. In East Asia, democracy and respect for human rights have replaced authoritarian rule in South Korea, Taiwan, the Philippines, and Indonesia.

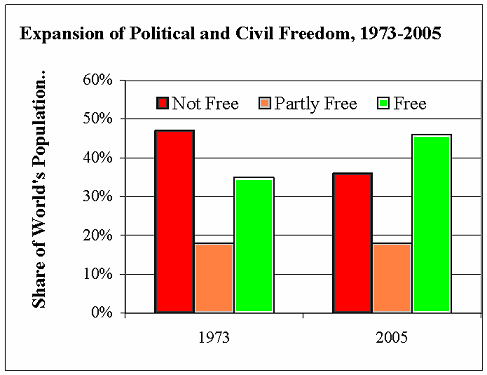

Freedom House, a human rights think tank in New York, measures the political and civil freedom each year in every country in the world. It classifies countries into three categories: “Free”–meaning countries where citizens enjoy the freedom to vote as well as full freedom of the press, speech, religion and independent civic life; “Partly Free”–those countries “in which there is limited respect for political rights and civil liberties”; and “Not Free”–“where basic political rights are absent and basic civil liberties are widely and systematically denied.” According to the most recent Freedom House survey, political and civil freedoms have expanded dramatically along with the spread of globalization and freer trade. In 1973, 35 percent of the world’s population lived in countries that were “Free.” Today that share has increased to 46 percent. In 1973, almost half of the people in the world, 47 percent, lived in countries that were “Not Free.” Today that share has mercifully fallen to 36 percent. The share of people living in countries that are “Partly Free” is the same, 18 percent.

In other words, in the past three decades, more than one-tenth of humanity has escaped the darkest tyranny for the bright sunlight of civil and political freedom. That represents 700 million people who once suffered under the jack boot of oppression who now enjoy the same civil and political liberties that we all take for granted.

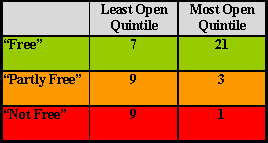

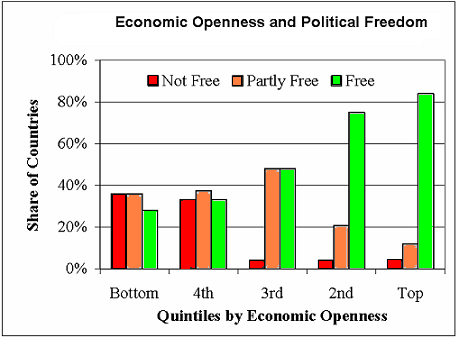

Next, I examined the relationship between economic openness in individual countries today and their record of human rights and democracy. To make this comparison, I combined the Freedom House ratings with the ratings for economic freedom contained in the Economic Freedom of the World Report. That study rates more than 120 countries according to the freedom to trade and invest internationally, to engage in business, access to sound money, property rights, and the size of government. The study is jointly sponsored by 50 think tanks around the world, including the Cato Institute, the Fraser Institute in Canada, and Norway’s own Center for Business and Society Incorporated, or Civita. When we compare political and civil freedoms to economic freedom, we find that nations with open and free economies are far more likely to enjoy full political and civil liberties than those with closed and state-dominated economies. Of the 25 rated countries in the top quintile of economic openness, 21 are rated “Free” by Freedom House and only one is rated “Not Free.” In contrast, among the quintile of countries that are the least open economically, only seven are rated “Free” and nine are rated “Not Free.” In other words, the most economically open countries are three times more likely to enjoy full political and civil freedoms as those that are economically closed. Those that are closed are nine times more likely to completely suppress civil and political freedoms as those that are open.

The percentage of countries rated as “Free” rises in each quintile as the freedom to exchange with foreigners rises, while the percentage rated as “Not Free” falls. In fact, 17 of the 20 countries rated as “Not Free” are found in the bottom two quintiles of economic openness, and only three in the top three quintiles. The percentage of nations rated as “Partly Free” also drops precipitously in the top two quintiles of economic openness.

A more formal statistical comparison shows a significant, positive correlation between economic freedom, including the freedom to engage in international commerce, and political and civil freedom. The statistical correlation remains strong even when controlling for a nation’s per capita gross domestic product, consistent with the theory that economic openness reinforces political liberty directly and independently of its effect on growth and income levels. One unmistakable lesson from the cross-country data is that governments that grant their citizens a large measure of freedom to engage in international commerce find it dauntingly difficult to deprive them of political and civil liberties. A corollary lesson is that governments that “protect” their citizens behind tariff walls and other barriers to international commerce find it much easier to deny those same liberties.

Even when we look at reform within individual countries, we see a connection. A statistical analysis of those countries shows a significant and positive correlation between the expansion of the freedom to exchange with foreigners over the past three decades in individual countries and an expansion of political and civil freedoms in the same country during the same period. Countries that have most aggressively followed those twin tracks of reform–reflected in their improved scores during the past two decades in the indexes for freedom of exchange and combined political and civil freedom–include Chile, Ghana, Hungary, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Portugal, and Tanzania. Twenty years ago, both South Korea and Taiwan were essentially one-party states without free elections or full civil liberties. Today, due in large measure to economic liberalization, trade reform, and the economic growth they spurred, both are thriving democracies where a large and well-educated middle class enjoys the full range of civil liberties. In both countries, opposition parties have gained political power against long-time ruling parties.

Our best hope for political reform countries that are “Not Free” will not come from confrontation and economic sanctions. In Cuba, for example, expanded trade with the United States would be a far more promising policy to bring an end to the Castro era than the failed, four-decades-old economic embargo. Based experience elsewhere, the U.S. government could more effectively promote political and civil freedom in Cuba by allowing more trade and travel than by maintaining the embargo. The folly of imposing trade sanctions in the name of promoting human rights abroad is that sanctions deprive people in the target countries of the technological tools and economic opportunities that nurture political freedom.

A More Democratic China?

In China, the link between trade and political reform offers the best hope for encouraging democracy and greater respect for human rights in the world’s most populous nation. After two decades of reform and rapid growth, an expanding middle class is experiencing for the first time the independence of home ownership, travel abroad, and cooperation with others in economic enterprise free of government control. The number of telephone lines, mobile phones, and Internet users has risen exponentially in the past decade. Tens of thousands of Chinese students are studying abroad each year.

China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001 has only accelerated those trends.

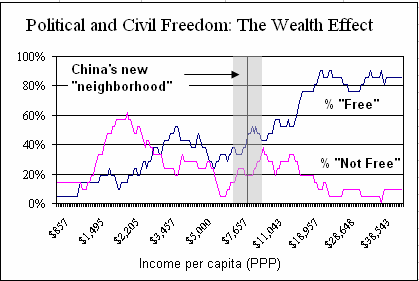

So far, the people of mainland China have seen only marginal improvements in civil liberties and none in political liberties. But the people of China are undeniably less oppressed than they were during the tumult of the Cultural Revolution under Mao Tse-Tung. And China is reaching the stage of development where countries tend to shed oppressive forms of government for more benign and democratic systems. China’s per capita GDP has reached about $7,600 per in terms of purchasing power parity. That puts China in the upper half of the world’s countries and in an income neighborhood where more people live in political and civil freedom and fewer under tyranny. Among countries with lower per capita incomes than China, only 27 percent are free. Among those with higher incomes, 72 percent are free. Only 16 percent are not free, and almost all of those are wealthier than China not because of greater economic freedom but because of oil.

By multiple means of measurement, political and civil freedoms do correlate in the real world with expanding freedom to trade and transact across international borders. Nations that have opened their economies over time are indeed more likely to have opened themselves to political competition and greater freedom for citizens to speak, assemble, and worship freely. And around the globe, the broad expansion of international trade and investment has accompanied an equally broad expansion of democracy and the political and civil freedoms it is supposed to protect.

The Peace Dividend of Globalization

The good news does not stop there. Buried beneath the daily stories about suicide bombings and insurgency movements is an underappreciated but encouraging fact: The world has somehow become a more peaceful place.

A little-noticed headline on an Associated Press story a while back reported, “War declining worldwide, studies say.” In 2006, a survey by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute found that the number of armed conflicts around the world has been in decline for the past half-century. Since the early 1990s, ongoing conflicts have dropped from 33 to 17, with all of them now civil conflicts within countries. The Institute’s latest report found that 2005 marked the second year in a row that no two nations were at war with one another. What a remarkable and wonderful fact.

The death toll from war has also been falling. According to the Associated Press report, “The number killed in battle has fallen to its lowest point in the post-World War II period, dipping below 20,000 a year by one measure. Peacemaking missions, meanwhile, are growing in number.” Current estimates of people killed by war are down sharply from annual tolls ranging from 40,000 to 100,000 in the 1990s, and from a peak of 700,000 in 1951 during the Korean War.

Many causes lie behind the good news–the end of the Cold War and the spread of democracy, among them–but expanding trade and globalization appear to be playing a major role in promoting world peace. Far from stoking a “World on Fire,” as one misguided American author argued in a forgettable book, growing commercial ties between nations have had a dampening effect on armed conflict and war. I would argue that free trade and globalization have promoted peace in three main ways.

First, as I argued a moment ago, trade and globalization have reinforced the trend toward democracy, and democracies tend not to pick fights with each other. Thanks in part to globalization, almost two thirds of the world’s countries today are democracies–a record high. Some studies have cast doubt on the idea that democracies are less likely to fight wars. While it’s true that democracies rarely if ever war with each other, it is not such a rare occurrence for democracies to engage in wars with non-democracies. We can still hope that has more countries turn to democracy, there will be fewer provocations for war by non-democracies.

A second and even more potent way that trade has promoted peace is by promoting more economic integration. As national economies become more intertwined with each other, those nations have more to lose should war break out. War in a globalized world not only means human casualties and bigger government, but also ruptured trade and investment ties that impose lasting damage on the economy. In short, globalization has dramatically raised the economic cost of war.

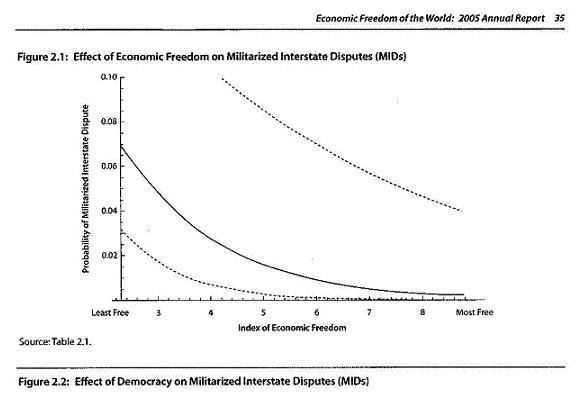

The 2005 Economic Freedom of the World Report contains an insightful chapter on “Economic Freedom and Peace” by Dr. Erik Gartzke, a professor of political science at Columbia University. Dr. Gartzke compares the propensity of countries to engage in wars and their level of economic freedom and concludes that economic freedom, including the freedom to trade, significantly decreases the probability that a country will experience a military dispute with another country. Through econometric analysis, he found that, “Making economies freer translates into making countries more peaceful. At the extremes, the least free states are about 14 times as conflict prone as the most free.”

By the way, Dr. Gartzke’s analysis found that economic freedom was a far more important variable in determining a countries propensity to go to war than democracy.

A third reason why free trade promotes peace is because it allows nations to acquire wealth through production and exchange rather than conquest of territory and resources. As economies develop, wealth is increasingly measured in terms of intellectual property, financial assets, and human capital. Such assets cannot be easily seized by armies. In contrast, hard assets such as minerals and farmland are becoming relatively less important in a high-tech, service economy. If people need resources outside their national borders, say oil or timber or farm products, they can acquire them peacefully by trading away what they can produce best at home. In short, globalization and the development it has spurred have rendered the spoils of war less valuable.

Of course, free trade and globalization do not guarantee peace. Hot-blooded nationalism and ideological fervor can overwhelm cold economic calculations. Any relationship involving human beings will be messy and non-linier. There will always be exceptions and outliers in such complex relationships involving economies and governments. But deep trade and investment ties among nations make war less attractive.

A Virtuous Cycle of Democracy, Peace and Trade

The global trends we’ve witnessed in the spread of trade, democracy and peace tend to reinforce each other in a grand and virtuous cycle. As trade and development encourage more representative government, those governments provide more predictability and incremental reform, creating a better climate for trade and investment to flourish. And as the spread of trade and democracy foster peace, the decline of war creates a more hospitable environment for trade and economic growth and political stability.

We can see this virtuous cycle at work in the world today. The European Union just celebrated its 50th birthday. For many of the same non-economic reasons that motivated the founders of the GATT, the original members of the European community hoped to build a more sturdy foundation for peace. Out of the ashes of World War II, the United States urged Germany, France and other Western European nations to form a common market that has become the European Union. In large part because of their intertwined economies, a general war in Europe is now unthinkable.

In East Asia, the extensive and growing economic ties among Mainland China, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan is helping to keep the peace. China’s communist rulers may yet decide to go to war over its “renegade province,” but the economic cost to their economy would be staggering and could provoke a backlash among its citizens. In contrast, poor and isolated North Korea is all the more dangerous because it has nothing to lose economically should it provoke a war.

In Central America, countries that were racked by guerrilla wars and death squads two decades ago have turned not only to democracy but to expanding trade, culminating in the Central American Free Trade Agreement with the United States. As the Stockholm Institute reported in its 2005 Yearbook, “Since the 1980s, the introduction of a more open economic model in most states of the Latin American and Caribbean region has been accompanied by the growth of new regional structures, the dying out of interstate conflicts and a reduction in intra-state conflicts.”

Much of the political violence that remains in the world today is concentrated in the Middle East and Sub-Saharan Africa–the two regions of the world that are the least integrated into the global economy. Efforts to bring peace to those regions must include lowering their high barriers to trade, foreign investment, and entrepreneurship.

Finally, those of us who live in countries that have benefited the most from free trade and globalization should rededicate ourselves to expending and institutionalizing the freedom to trade.

On a multilateral level, a successful agreement through the World Trade Organization would create a more friendly climate globally for democracy, human rights and peace. Less developed countries, by opening up their own, relatively closed markets, and gaining greater access to rich-country markets, could achieve higher rates of growth and develop the expanding middle class that forms the backbone of most democracies. A successful conclusion of the Doha Development Round that began in 2001 would reinforce the twin trends of globalization and the spread of political and civil liberties that have marked the last 30 years, and with it the further decline of war as an instrument of foreign policies. To set a good example, the United States, the European Union, Norway and other OECD countries should scrap their farm subsidies and all remaining trade barriers and urge other WTO members to respond in kind. Failure of the round would delay and frustrate progress and peace for millions of people.

Advocates of free trade and globalization, including the World Trade Centers Association, have long argued that trade expansion means more efficiency, higher incomes, and reduced poverty. The welcome spread of representative government and decline of armed conflicts in the past few decades remind us that free trade also comes with its own peace dividend.

Thank you.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.