Accompanying U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen’s just-concluded trip to China has been an avalanche of stories and punditry about how governments are preparing (or should prepare) for another “China Shock.” Chinese subsidies and industrial overcapacity, so the story goes, threaten to flood world markets with cheap imports of solar panels, EVs, and other products, producing widespread economic carnage in importing countries that’s similar to (if not worse than) what the first China Shock did in the 2000s. Warning against a “China Shock 2.0” was, in fact, one of Yellen’s big messages to the Chinese government, as she repeatedly asserted—including in a Monday press conference—that the United States will not simply sit idly by and let another China Shock happen.

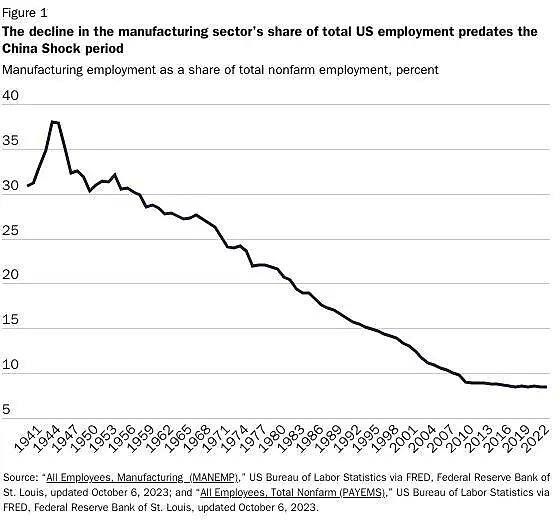

As we discussed last month, there’s some truth to the current political handwringing about Chinese overcapacity, which is driven by not only misguided industrial policy but also (and probably more so) a weak Chinese economy and depressed consumer demand. However, I’m returning to the issue today because almost every online discussion of China Shock 2.0 (including, alas, at our own Morning Dispatch!) gets major parts of China Shock 1.0 wrong—what it was, what drove it, what it caused, and/or what happened next.

Reading those summaries, you will inevitably think that 1) the China Shock was driven mainly by U.S. trade liberalization; 2) it devastated the U.S. economy, destroying more 2 million American manufacturing jobs and causing widespread social problems too; and 3) that these widespread harms are settled economic canon. Wanting the government to thwart another round of such devastation today—including via tariffs—would be an understandable response.

But there’s only one problem: Almost none of what I just said about the China Shock is actually correct.

What Is the ‘China Shock’?

Let’s start with the basics. The “China Shock” refers to both a 12‐year surge of Chinese imports into the United States and the first series of academic papers that analyzed it. As you can see from the following chart, the nominal value of Chinese goods imports into the U.S. started accelerating in the late 1990s and continued during the 2000s—thus, the “shock.”

The surge coincided with two important events that are forever linked to it: 1) the 2000 passage of U.S. law granting China permanent normal trade relations (PNTR) status, which cemented for Chinese imports the lower tariffs that the United States already applied to imports of almost all other nations; and 2) China’s official entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001. As the chart above shows, the surge moderated substantially after the Great Recession and effectively stopped by the middle of the 2010s (pre-Trump).

The academic discussion, however, was just getting started.

Following their 2013 paper on the same subject, economists David H. Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson published their seminal work on the issue, “The China Shock,” in 2016. According to their calculations, increased Chinese imports between 1997 and 2011 were directly or indirectly responsible for roughly 2 million lost U.S. jobs, including 985,000 in manufacturing. The most affected subsectors included industries with low‐skilled workers, such as apparel, textiles, footwear, and computer/electronic parts. When including local employment, the authors estimated total U.S. job losses of up to 2.4 million positions between 1999 and 2011 (the “official” China Shock period).

Since then, the same authors have examined the China Shock’s effects on other issues, such as marriage and drug addiction, again finding harms. Their papers have been joined by others showing similar employment results, such as one by economists Justin Pierce and Peter Schott focused on PNTR, and the collection of papers has supported still other economics research employing various methodologies and data—and often finding statistically significant damage to American workers and their communities from the surge in Chinese imports.

Combined, these papers form the academic backbone of not only the “China Shock” discussion, but also broader arguments against free trade and globalization as well as the current political narrative surrounding past U.S.‐China trade policy—as Yellen’s China trip and recent comments show. Unfortunately, folks writing about this stuff routinely misstate or misunderstand the China Shock research and the origins of the shock itself, and they ignore a library of other China‐related work that offsets—if not outright refutes—the China Shock papers’ conclusions.

Let’s tick through these mistakes one by one.

Mistake 1: U.S. Policy Wasn’t the Primary Driver of the China Shock

Both journalists and critics of U.S.‐China trade policy routinely assert that PNTR and China’s WTO entry, both U.S. policy choices, drove the China Shock. However, leaving aside whether U.S. officials really had much of a choice for either policy (itself an open question, as I detailed in 2020, given the surrounding events and realistic alternatives), history and academic research show that U.S. trade policy changes weren’t the main things fueling China’s improved export competitiveness (and thus the China Shock) in the 2000s.

First, PNTR did not actually open the United States to Chinese imports. Instead, the U.S. had annually granted China “most favored nation” (MFN) status (later changed to “normal trade relations”) every year since 1980, meaning the country’s imports faced no greater trade barriers than those from most other U.S. trading partners. Only once between 1990 and 2001 was China’s MFN status truly in doubt: in 1992, when a presidential veto was needed to maintain it. Thanks to two decades of uninterrupted MFN renewals, Chinese imports to the United States increased more than sixfold in the decade preceding PNTR, and—as a 1998 Congressional Research Service analysis detailed—the rational expectation of most U.S. importers was more of the same. There is some evidence that the certainty of permanent trade relations accelerated Chinese imports after PNTR was implemented (in turn causing U.S. job losses), but experts disagree about the magnitude of this effect because the uncertainty surrounding Congress’ annual MFN votes had evaporated by the late 1990s. (Less uncertainty means less PNTR effect on Chinese imports.)

More importantly, economists have repeatedly found that other factors—not PNTR or China’s WTO accession—were the main drivers of the China Shock. Economists Kyle Handley and Nuno Limão, for example, found that PNTR’s reduction in trade policy uncertainty accounted for only about one‐third of the growth in Chinese exports to the United States between 2000 and 2005. Mary Amiti and colleagues found similar results, attributing approximately two‐thirds of the trade effects on U.S. manufacturing not to PNTR but to China’s own tariff reductions, which counterintuitively make exporters more competitive. (Preliminary results from a new group of economists suggest that—again contra the narrative—China reduced domestic tariffs by a greater amount than was expected for nations joining the WTO.) Even the China Shock papers by Autor, Dorn, and Hanson (I’ll refer to them as ADH going forward) emphasize that China’s internal reforms—on privatization, trading rights, and (again) import liberalization—were the major contributors to China’s export surge in the late 1990s and 2000s.

In short, PNTR probably accelerated Chinese exports to the United States by reducing tariff uncertainty, but it was China’s own market‐based reforms—policies beyond U.S. officials’ control and ones China critics should cheer—that were the China Shock’s biggest drivers.

Mistake 2: The China Shock Didn’t Destroy 2 Million-Plus U.S. Manufacturing Jobs

The ADH China Shock papers are frequently characterized as showing that Chinese imports during the 2000s did serious damage to the U.S. economy writ large and especially to American manufacturing employment. But this gets three big points wrong about what the papers actually did and didn’t say:

First, the figure of 2.4 million lost jobs during 1999 and 2011 was the authors’ maximum (“upper bound”) estimate, with the more likely scenario (“central estimate”) being only about half that number. Just as importantly, only half of those job losses were in manufacturing—all the others were in local and supporting services. Those jobs matter too, of course, but common claims that the China Shock destroyed 2 million or more American manufacturing jobs are—by even the authors’ most extreme estimates—just plain wrong.

Second, the ADH papers focus strictly on job losses incurred by specific local labor markets because of the China Shock—they don’t account for everything else happening in the U.S. economy at the same time, including Chinese imports’ other effects. This methodological issue is really important, because a) the much-ballyhooed 2.4 million job losses (max) came amid an economy‐wide gain of approximately 2.2 million U.S. jobs (even as the labor market effects of the Great Recession persisted beyond 2011); and b) those 1 million lost manufacturing jobs (max) accounted for less than 20 percent of the total manufacturing job losses over the same timeframe—and a tiny fraction of the tens of millions of job separations that occur in the United States each year. Thus, even the China Shock papers themselves confirm that manufacturing job losses caused by Chinese imports were at best a significant contributor to—not the main driver of—total factory job declines during the 2000s.

Third, the authors’ major and novel contribution to the economics literature wasn’t actually the trade findings—imports and jobs have long been analyzed—but that displaced U.S. manufacturing workers didn’t adjust like economists expected and instead became unemployed or exited the labor force. This effect was more pronounced for workers without a college education and for low‐earning workers, and in their latest (2021) paper, ADH assert that the negative effects of the China Shock persisted all the way through 2019.

Americans’ lack of adjustment is important for lots of policy reasons (many of which I often discuss), but it also comes with several important asterisks that Autor, Dorn, and Hanson themselves bring up. They make clear that their findings relate to any significant economic disruption (e.g., technological change), not merely Chinese import competition. Thus, the trio asserts that policies addressing the problems identified in the China Shock papers should focus on helping workers adjust to trade or other disruptions, not stopping the disruptions from occurring (e.g., with tariffs or other forms of protectionism). As Hanson wrote in a 2021 article, “The China trade shock hurt many US workers and their communities. But so, too, have automation, the Great Recession, and the COVID-19 pandemic. And because the scarring effects of job losses are the same whether imports, robots, or a virus is responsible, responses to the damage should not depend on the identity of the culprit.”

Also, the trio notes that their China Shock work does not challenge the overall benefits of free trade for the U.S. economy; as the New York Times reported in 2016, for example, “Mr. Autor, like most economists, is still persuaded of the long‐established benefits that global trade confers on the economy as a whole.”

Those using the China Shock to advocate new U.S. protectionism have missed these crucial points.

Mistake 3: The China Shock Probably Didn’t Destroy Millions of American Jobs of Any Kind (on Net)

Although the ADH papers are frequently reported as the definitive take on the China Shock period and the economic effects of Chinese imports, many other peer-reviewed studies from well-respected economists call into question the somewhat bleak China Shock picture of a “post‐globalized America” with persistent job losses for the poorest and most uneducated workers, increased geographical disparities, and familial life filled with challenges. In fact, while most experts agree that Chinese import competition caused some American manufacturing workers to lose their jobs during the 1990s and 2000s, the debate still rages as to the scale of this disruption and the overall effects of Chinese imports on the U.S. workforce.

On manufacturing jobs, for example, several studies find that Chinese import competition was directly responsible for far fewer losses than the totals calculated in the China Shock papers. One of the most definitive reviews attributed only about 15 percent of lost U.S. factory jobs between 2000 and 2007 to the China Shock—a finding the White House Council of Economic Advisers recently highlighted in its 2024 Economic Report of the President. Other papers have found offsetting job gains from exports to China or smaller job losses when considering factors such as value‐added trade flows or the changes in the U.S. housing market, leading to estimates of net U.S. manufacturing job loss as low as 0.22 percent of nonfarm employment (i.e., just 300,000 jobs over a decade!). Wonkier methodological concerns raise further questions about the exact numbers put forth in the ADH papers.

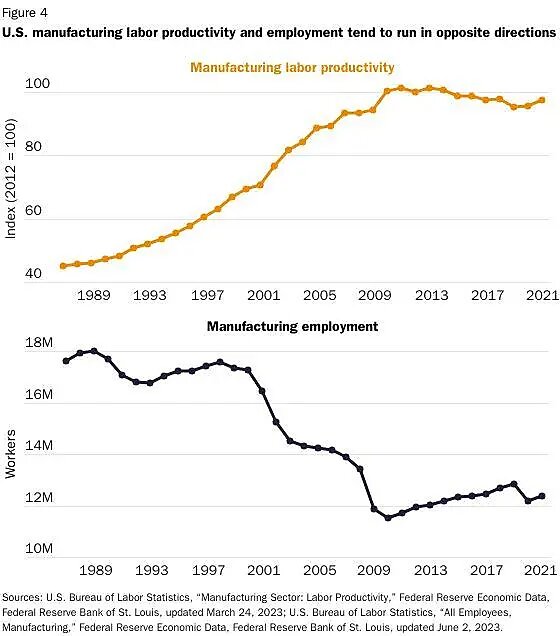

Other experts go even further and question not merely the China Shock papers’ numbers but their conclusions entirely. Economists Alan Reynolds and Philip Levy, along with former U.S. diplomat Charles Freeman, have argued that the China Shock likely caused an even smaller decline in U.S. manufacturing employment (if one at all) after accounting for other trends—especially productivity gains and non‐China imports. These and other scholars note that the manufacturing sector’s share of the U.S. workforce declined steadily before and during the shock period because of trade, technology, American workers’ increasing skill levels, and the economy’s natural transition to services—long-term trends that many other advanced economies (including net manufacturing exporters like Germany) experienced too.

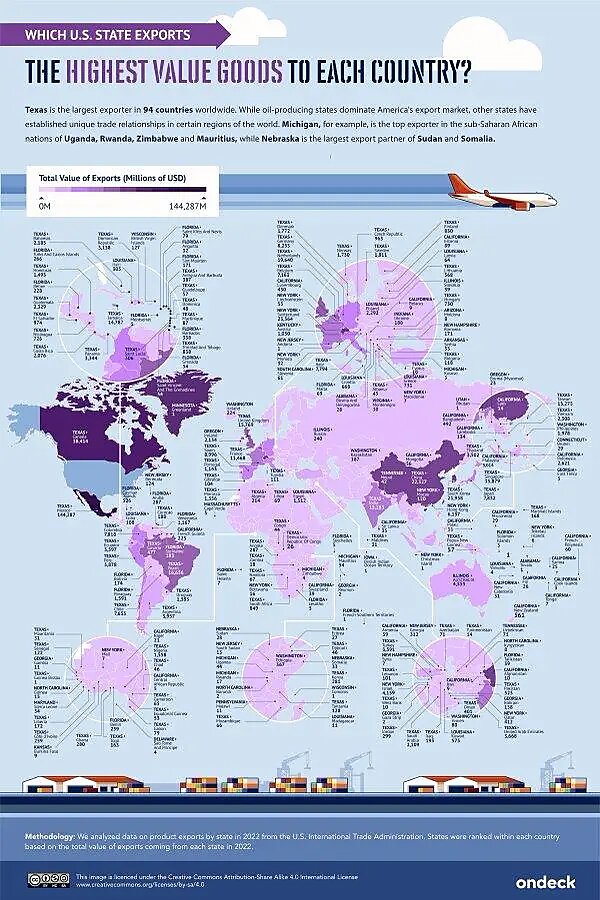

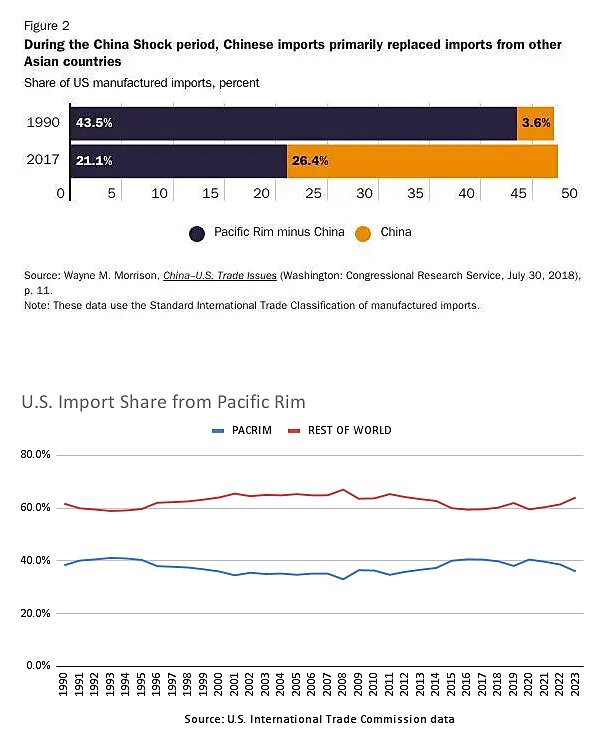

These experts add that, during the China Shock period, Chinese imports primarily replaced imports from other Asian countries, not U.S. production (and thus American jobs): As the charts below from the National Taxpayers Union’s Bryan Riley and the Congressional Research Service show, the overall portion of imports into the United States from Pacific Rim countries remained remarkably constant between 1990 and 2017, with only China’s share of those imports increasing substantially. During the same period, moreover, Americans’ import consumption remained stable.

Relatedly, research has found that most of the U.S. jobs and companies affected by the China Shock were in “late stage” industries like textiles and furniture (ADH concur), which were already facing intense import competition before China’s WTO accession and would therefore have eventually moved offshore regardless of the China Shock. Far from being a radical shock to these U.S. industries and workers, Chinese imports just moved up the timeline a bit.

I’m somewhat ambivalent about who exactly is right in this very wonky debate, but two things here warrant emphasis. First, nobody—not even ADH—is attributing the majority of U.S. manufacturing job losses to the China Shock, even during the peak 1999–2011 period, nor are they alleging widespread U.S. job losses overall. That narrative just doesn’t fit the data.

Second, recent events do seem to corroborate at least some of the China Shock critics’ main points about the extent of U.S. factory jobs lost. Between 2010 and 2023, for example, the U.S. economy gained more than 1.5 million manufacturing jobs; imported goods from China increased substantially (inflation-adjusted); and manufacturing productivity stagnated. That indicates (superficially, at least) that productivity, not Chinese imports, has been the bigger driver of overall U.S. factory employment gains and losses—at least over the long term. Here’s the telling chart:

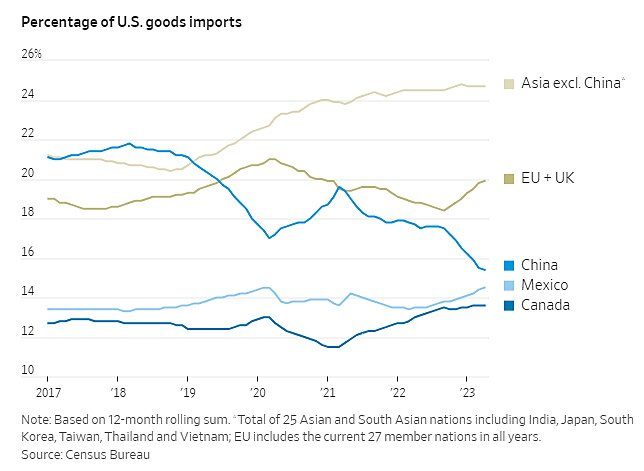

Furthermore, recent U.S. tariffs on Chinese imports—imposed by President Donald Trump and continued by the Biden administration—caused Chinese imports to plateau and imports from alternative countries, such as Mexico, Vietnam, and India, to surge. This supports the notion that Chinese imports displaced goods from other developing nations, not ones made in the United States (by American workers).

Along with the contradictory research on the China Shock period, these new points suggest—at the very least—that we shouldn’t just parrot the top-end ADH manufacturing jobs figure as gospel.

Yet here we are.

Mistake 4: The China Shock Didn’t Devastate the U.S. Economy (and, in Fact, Probably Provided a Small Boost on Net)

While experts disagree about the manufacturing jobs numbers, they (including ADH) uniformly recognize that the China Shock’s “winners” outnumbered its “losers” in the United States, and thus that the net economic benefit for the nation was actually positive. This, again, stems from things that ADH didn’t examine in their original papers.

First there’s the question of what Chinese imports did to other U.S. jobs in other places (i.e., not the jobs and communities hurt by the shock). Nicholas Bloom and colleagues, for example, concur with ADH that the China Shock caused U.S. manufacturing job losses, especially for those without college degrees, but they add that the losses were fully offset by gains in service jobs in other regions. Several other studies (see this Lorenzo Caliendo and Fernando Parro paper for a review of the academic literature) have similarly found that a decline in U.S. manufacturing jobs during the China Shock period was accompanied by increases in American service‐sector jobs—and often well-paying ones at the same manufacturing companies. The results from another group of economists were even more positive: After accounting for the effects of Chinese imports throughout the supply chain, specific jobs were indeed lost, but overall U.S. employment and wages increased, even in regions that experienced large manufacturing employment declines (contra ADH).

Second, the original ADH China Shock papers didn’t examine the consumer effects of trade with China for the United States. Other economists have filled this gap, again with more optimistic results. Xavier Jaravel and Erick Sager, for example, found that for each percentage point increase in Chinese imports, consumer prices fell by nearly 2 percentage points, with savings from both imports and domestically produced goods (thanks to heightened competition). Notably, middle‐ and low‐income households enjoyed a disproportionate amount of these benefits, as the most affected products were those often sold at big‐box retailers, such as Target and Walmart. As the 2024 Economic Report of the President also just noted, other studies have found Chinese imports to have provided similar reductions in consumer prices—“almost 90 percent of the U.S. population saw an increase in purchasing power”—as well as significant benefits for American manufacturers that consume imported inputs.

Even ADH themselves have recently acknowledged these consumer benefits, which their earlier work excluded. Their 2021 reassessment of the China Shock found that once Chinese imports’ pro-consumer effects were considered (using Jaravel and Sager’s estimates), only 6.3 percent of the U.S. population—or 82 of the 722 U.S. localities (commuting zones) examined—experienced net losses from that same import competition. This represents a far smaller share of China Shock “losers” than that found in the authors’ original estimates.

Finally, the ADH papers didn’t examine China Shock’s overall impact on U.S. living standards (called “welfare” in econ-speak). Here, again, other papers have found positive effects—in line with previous research on trade liberalization. Caliendo and Parro, in particular, find that between 1995 and 2011 the United States experienced an aggregate welfare gain of 3.4 percent due to trade with China. Other research also found gains in overall welfare, with sizable majorities of Americans (though of course not all) benefiting from this bilateral trade. Summarizing this research, Caliendo and Parro state that “aggregate gains from trade are widely agreed upon by trade economists, and the increased trade integration between the United States and China over the past 20 years has allowed researchers to confirm this view.” In their 2021 paper, ADH agree with this conclusion.

Funny how no one mentions it, eh?

Mistake 5: The China Shock Doesn’t Justify Tariffs Today

Another area of expert agreement is that China Shock 1.0 doesn’t justify tariffs or other trade restrictions today. As Adam Jakubik and Victor Stolzenburg note, for example, “The literature on the local labour market effects of Chinese import competition has been cited extensively as an argument for limiting trade with China despite the fact that the results do not support this conclusion.” They add that “there is no case for limiting trade with China” because “US local labour market adjustment to the China Shock has largely concluded.”

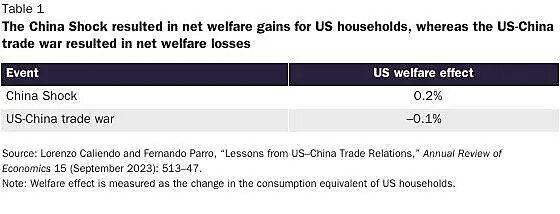

Other economists base their conclusion on recent U.S. experience following tariffs on Chinese imports applied during the Trump administration. Caliendo and Parro, for example, found that the tariffs—and China’s inevitable retaliation—reduced consumption, wages, manufacturing exports, and aggregate welfare—a stark contrast to the China Shock’s small net gains.

Other economists found that the tariffs didn’t reverse China-related manufacturing job losses and, in fact, cost factory jobs on net. Of the few industries and states that did see manufacturing employment growth during the trade war, the gains were very modest—if at all. ADH in a brand new paper (with Anne Beck) conclude much the same, finding that the tariffs’ employment effects were “a wash” at best and “mildly negative” at worst.

ADH’s 2021 paper summarized the expert consensus (emphasis mine):

The favored solution of populist politicians to regional distress is to raise import barriers and block immigration. Indeed, the Donald J. Trump administration cited the adverse impacts of the China trade shock to justify taking aggressive trade action against China. The subsequent US-China trade war succeeded in elevating US product prices but not in expanding employment in import-protected sectors. We are aware of no research that would justify ex-post protectionist trade measures as a means of helping workers hurt by past import competition.

Pretty definitive, eh?

So, About That ‘China Shock 2.0’

The aforementioned review isn’t just academic. As Yellen’s recent comments and the accompanying commentary make clear, policymakers and pundits intend to model their response to “China Shock 2.0” based on their understanding of China Shock 1.0. And if the White House and Congress truly (and wrongly) believe that the China Shock was caused by U.S. trade policy, devastated both U.S. manufacturing employment and the U.S. economy more broadly, and can be corrected with tariffs, then their response to 2.0 could be far more draconian, harmful, and misguided than if they had a more accurate understanding of the economics literature.

Indeed, experts also agree that the China Shock, regardless of its effects, has been over for at least a decade and won’t be repeated—by China or by any other emerging economy. As ADH explained in their 2021 paper, for example, “It is now clear that the China trade shock as we understand it appears to have stopped intensifying a decade ago” because it “was about China’s one-time transition to a market economy.” AEI’s China expert Derek Scissors told TMD much the same thing last week:

“The first China shock in manufacturing employment and manufacturing capacity is much bigger than anything that can happen now because it already happened,” Scissors told TMD. “This is nothing like that kind of scope.”

Put simply, because decades-long, fundamental changes to China’s economy on things like property rights and privatization (not U.S. trade policy!) were what drove the first China Shock, it’ll dwarf any future wave of subsidy-driven imports that so-called “China Shock 2.0” might bring (to the extent they even materialize). And because the only other developing country of China’s size, India, is already a market economy and WTO member, it too won’t be causing a “China Shock” in the future. (Vietnam is arguably not a market economy but is much smaller than China and acceded to the WTO in 2007, and all other nations still awaiting these moves are much too small to have a major economic impact.)

That said, Scissors is right to add that—just because a new wave of Chinese imports won’t be as economically consequential as the last one—that “doesn’t mean we shouldn’t get ready—we should.” But, given what we really know about the original China Shock, a sound U.S. policy response would recognize the true scope of the “overcapacity” issue today, the costs and benefits of imports, the costs and inefficacy of more and higher U.S. tariffs, and the need for better U.S. adjustment policy in response to whatever shock comes next, regardless of its origins.

Given what I’ve been reading, however, I’m not holding my breath.

Chart(s) of the Week