Executive Summary

The National Research Council and the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) published groundbreaking investigations into the economics of immigration in 1997 and 2017. Both publications contained thorough literature surveys compiled by experts, academics, and think tank scholars on how immigration affects many aspects of the U.S. economy. The 2017 NAS report included an original fiscal impact model as a unique contribution to immigration scholarship. Its findings have been used by policymakers, economists, journalists, and others to debate immigration reform. Here, we acquired the exact methods used by the NAS from its authors to replicate, update, and expand upon the 2017 fiscal impact model published in the NAS’s The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration.

This paper presents two analyses: a measure of the historical fiscal impacts of immigrants from 1994 to 2018 and the projected long-term fiscal impact of an additional immigrant and that immigrant’s descendants. An individual’s fiscal impact refers to the difference between the taxes that person paid and the benefits that person received over a given period. We use and compare two models for these analyses: the first follows the NAS’s methodology as closely as possible and updates the data for more recent years (hereafter referred to as the Updated Model), and the second makes several methodological changes that we believe improve the accuracy of the final results (hereafter referred to as the Cato Model). The most substantial changes made in the Cato Model include correcting for a downward bias in the estimation of immigrants’ future fiscal contributions identified by Michael Clemens in 2021, allocating the fiscal impact of U.S.-born dependents of immigrants to the second generation group, and using a predictive regression to assign future education levels to individuals who are too young to have completed their education. Other minor changes are discussed in later sections.

Immigrants have a more positive net fiscal impact than that of native-born Americans in most scenarios in the Updated Model and in every scenario in the Cato Model, depending on how the costs of public goods are allocated. The Cato Model finds that immigrant individuals who arrive at age 25 and who are high school dropouts have a net fiscal impact of +$216,000 in net present value terms, which does not include their descendants. Including the fiscal impact of those immigrants’ descendants reduces those immigrants’ net fiscal impact to +$57,000. By comparison, native-born American high school dropouts of the same age have a net fiscal impact of −$32,000 that drops to −$177,000 when their descendants are included (see Table 31). Results also differ by level of government. State and local governments often incur a less positive or even negative net fiscal impact from immigration, whereas the federal government almost always sees revenues rise above expenditures in response to immigration. With some variation and exceptions, the net fiscal impact of immigrants is more positive than it is for native-born Americans and positive overall for the federal and state/local governments.

Introduction

A standard complaint about immigration is that it is costly to taxpayers. Immigrants are often thought to have negative fiscal impacts, meaning they pay less in taxes than they receive in government benefits. Although the lifetime fiscal impact of an entire demographic group is difficult to measure, our results strongly imply that the opposite is true and that immigrants are a net fiscal benefit.

We used a fiscal impact model developed by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) for its 2017 report The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration to study the fiscal impact of immigrants compared with native-born Americans.1 This report explores questions such as the following: Do future immigrants arriving at a certain age and education level contribute positively or negatively to the country’s finances? Will their children pay more in taxes when they grow up than they receive in other benefits now? What is the overall impact of immigrants currently in the country compared with that of current native-born Americans?

The NAS fiscal impact model uses a generational accounting method to predict the fiscal impact of immigrants on the budgets of the federal and state/local governments over a 75-year period. It then presents the fiscal impact in net present value (NPV) terms, discounted by 3 percent. Generational accounting measures how much each adult generation, on a per capita basis, is likely to pay in taxes net of transfer payments. NPV refers to the total lifetime fiscal impact of an individual and their potential descendants, taking into account the likelihood of survival, emigration, fertility, and other relevant factors. These methods are the best for estimating how immigrants affect government finances over their life cycles because government benefits received and taxes paid vary predictably over a person’s lifetime.2 Benefits received are typically lower than taxes paid during working years and higher during childhood and old age.

The NAS model makes average fiscal projections for immigrants, depending on their age of arrival and level of education. Those projections depend on historical data and projections of future government spending levels, tax rates, economic growth, return migration, and demographics.3 We first replicated the NAS fiscal model for data from the years 1994–2013, the range for the NAS’s original research. To our knowledge, we are the first outside scholars to replicate the NAS fiscal impact model. The minor differences between our replication and the original are purely the result of revisions to the same underlying data since the publication of the NAS study in 2017, and we did not report those results for that reason. Next, we updated the NAS model to include 2014–2018 data without making changes to the NAS methodology. The results of this model, which we call the Updated Model, are similar to the original 2017 NAS study. In general, we find that the fiscal impacts of immigrants are more positive at the federal level and more negative at the state/local level compared with native-born Americans. In total, we find that immigrants are more fiscally positive than native-born Americans.

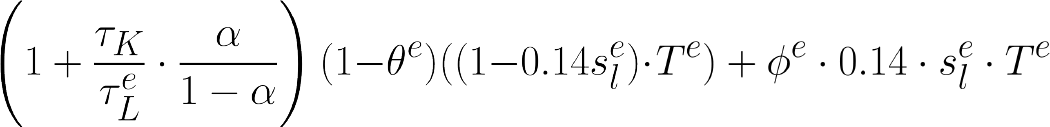

Lastly, we constructed a model with methodological changes to the NAS model, which we call the Cato Model. We addressed a bias to immigrants’ tax receipts identified by Michael Clemens in 2021 by combining the generational accounting model with a simple economic model that accounts for the extra taxes paid by additional capital investments made in response to immigration-induced population growth.4 We also allocated the fiscal impact of U.S.-born dependents of first-generation immigrants to the second-generation group, used a predictive regression to assign future education levels to individuals who are too young to have completed their education, and made several smaller adjustments discussed in later sections. Even with those changes, the results of the Cato Model confer a similar conclusion to those produced by the Updated Model, although the NPV of the overall fiscal impact of immigrants is more positive in the Cato Model. This paper presents two analyses: a measure of the historical impacts of immigrants and the predicted long-term fiscal impact of an additional immigrant and that immigrant’s descendants.

We updated the NAS fiscal impact model and created a Cato Model for three reasons. The first reason was to uncover important truths about how immigrants affect government finances. The second was so the Cato Institute can become a resource for the public, policymakers, academics, members of the media, and others who want to understand how immigrants affect government finances today and in the future. Cato scholars will be able to revise the Updated Model and the Cato Model with more-recent data to study policy shocks and to evaluate the budgetary impact of real or proposed changes in immigration policy. The third reason was to identify how much government spending programs would have to be adjusted to improve the fiscal impact of immigration, which will be especially valuable the next time Congress considers immigration reform. Describing the fiscal impact of immigration in a format that is broadly parallel to that of the 2017 NAS report means that our text and formatting are similar to that of the 2017 NAS report. Although we endeavored to cite liberally, this paper contains half-sentences, sentences, or paragraphs with verbiage similar to that of the 2017 NAS report.

Updated Model Methodology

The fiscal impact of immigration in chapter 8 of the 2017 NAS report The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration was broken into two substantive sections. The first estimates the historical fiscal impact of immigrants from 1994 to 2013 and relies primarily on cross-sectional tax, income, and public expenditure data from the Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) of the Current Population Survey (CPS). The second estimates the future impact immigrants and their children will have on public finances. In addition to using CPS data, those projections use estimates of demographic changes, including education, fertility rates, life expectancies, and immigration and emigration rates. Projections of fiscal aggregates used to estimate demographic group impacts are from long-term budget projections produced by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO). For the historical portion of our analysis, we follow the NAS methodology, with minor alterations where better data were available. However, the CBO’s switch from 75-year to 30-year projections forced us to shorten the projected fiscal impacts by 45 years in our updated analysis, making a comparison of our findings with the 2017 study difficult, but the shorter time frame means the projections are more likely to be accurate. For context, a 75-year forecast of today’s budget would have been made during the Truman administration.

Historical Fiscal Impacts (1994–2018)

As in the NAS 2017 report, our immigrant and education groups are as follows: The first generation consists of foreign-born individuals, excluding those born abroad who gain citizenship at birth because their parents are U.S. citizens. The second generation includes U.S.-born persons with at least one foreign-born parent. The third-plus generation includes all U.S.-born persons who were born to U.S.-born parents (see Box 1). Persons with one foreign-born parent and one native-born parent are split equally between the second and third generations.5 The education groups are less than high school, high school graduate, some college but no college degree, college graduate, and graduate-level education. This educational disaggregation is necessary because fiscal impacts vary by income level, which is closely correlated with an individual’s education level.

Except in the sections involving dependents, we used individuals rather than households as the unit of measurement, which allowed us to avoid making assumptions about household composition over time and to directly measure the impact of an additional immigrant arriving in the United States. Households change through births, deaths, divorces, the departure of children, new family members arriving possibly from abroad, job losses, and other reasons. Focusing on individuals also removes the complication of multigenerational households, in which some members are immigrants and others are native born.6 Taxes, expenditures, and other benefits are thus assigned to the individuals who are most directly related to them. For most flows, such as personal income taxes or retirement income, this process is simple. Other flows, such as taxes jointly filed by couples or childhood education expenditures, require assumptions to allocate them to individuals. Some of those flows are allocated by program participation or by generation group. For example, federal refugee aid is split equally among all immigrants because we cannot identify refugees in the CPS. Further details on these assumptions can be found in Appendix A.

We follow the NAS 2017 construction of eight cost-allocation scenarios. Half the scenarios use an average-cost method and half a marginal-cost method.7 Theoretically, the cost to a government for providing public goods to one additional immigrant is zero. This assumption is captured under the marginal-cost scenarios, in which the costs of public goods—such as defense spending, subsidies, and interest payments—are assumed to be zero for individual immigrants. However, because the cost of some public goods increases with usage (i.e., congestion), the average cost method allocates these costs equally across the entire population. The scenarios are defined in Box 2.

Under Scenarios 1–4, both immigrants and native-born Americans pay a portion of the cost of public goods. Under Scenarios 1, 3, and 4, those public goods include defense, foreign aid, state/local-level subsidies, and interest payments (both federal and state). Only natives pay those costs under Scenarios 5–8. Scenarios 2 and 6 exclude interest costs because they represent past expenditures that are not attributable to a new immigrant. Scenarios 3 and 7 reduce immigrants’ sales and consumption taxes under the assumption that immigrants send 20 percent of their income to their home countries as remittances. Scenarios 5 and 8 omit capital income taxes for immigrants who have been in the United States for less than 10 years because recent immigrants typically have lower rates of stock ownership.8 This paper primarily focuses on Scenarios 1 and 5 because allocating the cost of public goods affects immigrants’ fiscal impacts more than any other assumption in these scenarios.

Data for the historical fiscal cost estimates come primarily from the Current Population Survey’s Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC). The CPS is a monthly household survey conducted by the Census Bureau and the Bureau of Labor Statistics that contains information on education, labor force statistics, and personal demographics. Our sample is restricted to 1994–2018 for several reasons. Before 1994, questions on birthplace, citizenship, and parental birthplace were not included in the survey. And although ASEC samples for the years 2019 and 2020 are available at the time of writing, they lack retirement income data, which are needed to estimate the fiscal impact of individuals at older ages. The household-level variables in the CPS are allocated among household members according to the assumptions outlined in Appendix A. Other benefits are allocated equally to individuals in a particular group, such as refugee aid to immigrants. Aggregate public expenditures are divided equally among all individuals in the sample (see Appendix A).

Some fiscal flows require alternative data sources. For public elementary and secondary school spending, we used state per-pupil current spending from the Census Bureau’s Annual Survey of School System Finances for the years 1994–2018.9 We assumed 100 percent enrollment for elementary and middle school students (ages 5–14). For high school students, we applied a half weight to those enrolled half-time and for elementary or junior high students (5‑to-14-year-olds) and assumed 100 percent enrollment. Those assumptions follow methods from the NAS 2017 report.

Because the CPS does not estimate the number of people living in institutions, we used the American Community Survey (ACS) to adjust each flow.10 This adjustment is particularly important for estimating Medicare expenditures, as a large fraction of elderly individuals live in nursing homes. We used Integrated Public Use Microdata Series ACS samples for the years 1980, 1990, and 2000–2019 and interpolated for years without a sample.11 Individuals are separated into two groups depending on their immigration status. Individuals are defined as institutionalized if they live in group quarters (GQ = 3). As the ACS does not ask individuals for their parents’ birthplace, second and third-plus generations are not distinguishable. Institutionalized estimates were created for native-born Americans (second-plus generations). Thus, we assumed that the proportion institutionalized is the same for both second and third-plus generations. Population estimates are also adjusted to the Census Bureau’s reports of the annual resident population.12

Following the NAS 2017 approach, we adjusted each demographic group’s estimates of fiscal flows to a set of aggregate controls. Those data come from three sources: the Bureau of Economic Analysis National Income and Product Accounts, the Office of Management and Budget historical outlay tables, and health insurance data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.13

For the historical analysis, we made two notable data changes from the NAS 2017 report. An important component of estimating the cost of elementary school education is English proficiency, as it is related to proportioning public school spending for English as a second language at the state and local levels. In the NAS 2017 report, schoolchildren—as surveyed by the ACS—were defined as having limited English proficiency if they were an immigrant and “did not speak English at home” or were reported to “not speak English well” or “not speak English” at all according to the definitions of the ACS’s measures of English proficiency.14 In our analysis, an immigrant schoolchild with limited English proficiency is someone who speaks English “not well” or “not at all” or “does not speak English at home” and does not speak English “well” or “very well.”15

The second change relates to the estimate of Medicare and Medicaid expenditures. Because the CPS reports Medicare and Medicaid participation but not the amount of funds received by an individual, we needed to rely on other sources. The authoritative source on national health care expenditure is the National Health Expenditure Accounts (NHEA).16 When the NAS published its 2017 report, it reported only per capita health care expenditures by age group. The NHEA now release more-detailed age and gender health care expenditure data. For this update, we made use of previously unavailable per-enrollee Medicare and Medicaid expenditures by age group and gender. Those data allowed us to more accurately allocate Medicaid funds because Medicaid is used at higher rates by young Americans. Per capita estimates are not sensitive to this distinction, as most health care is consumed by the elderly population.17

The 2017 NAS report did not include government subsidies for the purchase of health insurance on the health exchanges, also called health insurance marketplaces, as established under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA health exchanges were certified and operational on January 1, 2014, so they fell outside the fiscal window of 1994–2013, as analyzed by the 2017 NAS report. CPS only began collecting data on the marketplace insurance use rates in 2019. As a result, our descriptive analysis of the net fiscal impact of immigrants and native-born Americans for 2014–2018 does not include that important government health care subsidy. Our back-of-the-envelope estimate of health insurance marketplace premium subsidies using data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services on state ACA subsidy averages and the CPS found that 3.43 percent of first-generation immigrants, 2.26 percent of second-generation immigrants, and 1.69 percent of the third-plus generation consumed those subsidies in 2019–2020.18 The average dollar amount for the first and second generations was $471, and the third-plus generation consumed $505 for the same 2019–2020 period. These calculations are too crude to include in the Updated Model or Cato Model of the current and historical net fiscal impact estimates, but they do indicate that the omission of ACA health insurance premium subsidies probably does not radically alter our results for the 2014–2018 period. However, our projections for the next 30 years include ACA subsidies because they are a component of the CBO 30-year fiscal outlook. Future versions of this report will include the ACA subsidies in the current and historical 2014–2018 period if and when those microdata become available.

In the estimates that follow, we explore the population and age structures of first-generation immigrants, the second generation, and third-plus generation Americans as defined previously. We then show how differences in age, education, and income affect taxes paid and benefits received. Some analysis involves allocating the costs of children and other dependents to their caregivers (see Box 3). In this case, the individual-level analysis does not hold, so we used a household-level analysis. Estimates often use single-year samples, whereas others use an average over three years. We chose to use single-year instead of three-year averages to smooth outliers and to keep as close as possible to the NAS 2017 methods.

Future Impacts (2018–2051) Methodology

The historical and current fiscal impacts of immigration on federal and state/local government budgets do not necessarily determine the future flows, as demographic and budgetary changes will affect taxes paid and benefits received. Changes in U.S. fiscal policy, immigration policy, fertility rates, life expectancies, the age of arrival of immigrants to the United States, return emigration rates, educational attainment, and broader trends in international immigrant flows all affect the future impact that immigrants will have on U.S. government finances. We updated the NAS 2017 model that answers questions such as the following: Do future immigrants arriving at a certain age and education level contribute positively or negatively to the country’s finances? Will their children pay more in taxes when they grow up than what they receive in other benefits now? What is the impact of immigrants currently in the country compared with current native-born Americans?

Future estimates were made for the average person in each age, education, and immigration demographic cell. To reiterate, the education groups are less than high school, high school graduate, one to four years of college, a four-year college degree, and more than four years of college. For the immigration groups, we added a category for recent immigrants who arrived within the past five years. Comparing recent immigrants with all immigrants demonstrates how changes in immigrant demographics will affect fiscal flows over time. The range of the age profiles is constrained by the CPS, which has a maximum age of 80. Using fertility estimates, we also forecasted fiscal flows for the children of immigrants and native-born Americans. The age-specific fertility rates of immigrants and native-born Americans are calculated using the ACS’s five-year 2019 sample and measure the average number of births per 1,000 women of childbearing ages. We (in both the Cato Model and Updated Model) and the NAS used age-specific fertility rates because they are less affected by changes in the population age composition and are thus more useful for comparing subgroups over time.19

Because educational attainment has significant impacts on an individual’s tax payments and welfare receipts, we constructed a simple linear regression following the NAS method in 2017 to predict the future educational attainment of each immigrant group.20 Using CPS samples, we identified a group of parents in a specific year who are at least 25 years old and thus are assumed to have completed their education and who have children aged between 10 and 16.21 We then identified the average education level of those children 15 years later, when they are 25 years old or older, and regressed the children’s average years of schooling on their parents’ average years of schooling. Separate regressions are done for parents born in the United States, Mexico, Central America (without Mexico), South America, Canada, Europe, Africa, East Asia, Southeast Asia, and Other Asia (Eurasia, Central Asia, and Oceania) because the impact of a parent’s education on his or her child’s education varies by region of birth.22 This process provides us with an estimate of increases in educational attainment over time, dependent on the parent’s birthplace. Additional details on this regression can be found in Appendix A.

Average tax payments and benefits for each age, education, and immigrant group are constructed using the smoothed profiles from 2016–2018 estimated in the following section. They are then extended using population projections by age and nativity from the Census Bureau’s 2017 estimates and adjusted by estimated aggregates given by the three alternative budget scenarios produced by the CBO, as defined in Box 4, until 2051.23 Then, for each cohort—that is, ages ranging from birth to 80, the five education groups, and the three immigrant groups—the tax and benefit averages are summed and weighted by probability of survival. For immigrants, the probability of remaining in the country is also applied. For the Updated Model, we continued to use the emigration probabilities estimated by the NAS.24 A discount rate of 3 percent is applied to construct final NPV flows.25 The net future impact of the group for a particular age is interpreted as the discounted sum of future taxes and benefits for the group of that age in 2018 (measured in 2012 dollars), when the future projections begin.

As with the historical impact component, we constructed estimates varying the treatment of public goods. The analysis that follows includes categories that exclude all public goods; include public goods such as defense spending, subsidies, and rest-of-world payments; and include public goods covering defense spending, subsidies, rest-of-world payments, and interest payments. Congestible public goods include public administration, police, firefighting services, and incarceration costs.26 Estimates excluding public goods underestimate the public benefits each demographic group receives, and estimates including public goods overestimate the public benefits each demographic group receives.

Because budgets are more difficult to predict the further into the future estimates go, we did not make assumptions relating to future tax and spending policy beyond what is included in the CBO’s long-term budgetary projections.

Table 1 shows the averages in budgetary growth rates over the period surveyed. Compared with the 2017 report, expected growth in taxes decreased 1.04 percent under the “CBO long-term budget outlook” scenario, and discretionary spending decreased 0.48 percent. As the U.S. population continues to age, benefits consumed by the elderly are expected to increase rapidly.

30-Year versus 75-Year Projections

The methodology in this report broadly follows the NAS 2017 model except for one significant change. Beginning in 2015, the CBO stopped publishing 75-year projections and switched to 30-year projections for all but select population and economic topics. That change has the potential to create very biased and incomparable results for our update. The shorter time horizon of the 30-year estimate may make younger immigrants appear more fiscally positive than they really are because it would exclude many of their retirement years and reduce their consumption of Social Security and Medicare. To test whether those changes would be a problem, we constructed net fiscal impacts by age group using the 2013 NAS profiles over a 75-year time frame in Figure 1 and the 2018 updated profiles over 30 years in Figure 2. The results are different in Figures 1 and 2, but the distribution in the 30-year and the 75-year projections is nearly identical. Discounting future benefits received, taxes paid, and different time horizons explains the difference in the results in the two figures. However, the two figures have the same shape, which allays our fears that a different time horizon for the CBO’s projections would reduce this paper’s comparability with the 2017 NAS study.

The total fiscal flows using the 30-year projections are lower, reflecting the reduction in years covered. For immigrants arriving at older ages, the net impact is slightly lower in our 2018 estimates compared with the 2013 report because many of those individuals die within 30 years. However, for the immigrants arriving at younger ages, much of the positive impact from accrued taxes is lost with the shorter period of analysis. For our analysis, we compared the 30-year impact of immigrants with native-born Americans of similar age and education levels rather than reporting total net fiscal impacts for immigrants only, as was published in the NAS 2017 study, to avoid any interpretational difficulties resulting from the shorter time analyzed. Although not being able to update the NAS 2017 lifetime impacts of immigrants—a central goal of the report—is unfortunate, the shorter time frame includes less uncertainty in budgetary developments over time.

Historical Impacts under the Updated Model

This section analyzes the historical impact of immigrants and native-born Americans on federal and state/local budgets from 1994 to 2018. For context, we discuss important policy and demographic trends during the period and the changes to those trends since 2013.

A Changing Policy Environment

The fiscal model in The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration, published by the NAS, uses data from the 1994–2013 period to analyze and predict the fiscal impact of immigration. The report was released at the beginning of a new presidential administration in 2017. Our update extends the period analyzed to include three major changes to immigration and fiscal policy undertaken during the then newly elected Trump administration.

The first major change affected immigrant welfare use. The Trump administration proposed and finalized a public charge rule that sought to deny green cards to immigrants who could consume welfare benefits according to a government-established criterion.27 The public charge rule did not directly reduce noncitizen immigrant access to benefits or their consumption of welfare. Instead, the public charge rule sought to deny green cards to immigrants who might receive welfare at some point in the future.28 The direct effect of the public charge rule on welfare consumption would not show up in our report because it was proposed in 2018 and finalized in 2019, the last year that we analyzed.29 However, the public charge rule could have indirectly reduced immigrant noncitizen welfare consumption in 2017 and 2018 through a so-called chilling effect. The chilling effect describes the reduction of immigrant consumption in response to fears of increased immigration enforcement or the threat of losing legal status from consuming benefits.30 Although the public charge rule was neither proposed nor enacted during the period this report studies, rumors of it combined with increased government enforcement of immigration laws could have induced a chilling effect among noncitizens.

The second major change was the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) in December 2017, which significantly cut individual and corporate tax rates.31 The third major change was the steady increase in federal spending, the deficit, and the national debt during the Trump administration.32 State/local tax and spending policies also changed from the period analyzed by The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration to the 2016–2018 period analyzed here.33

The Age Structure of Immigrant and Native Populations

Immigrants and native-born Americans have different age distributions. Figure 3 shows the age distribution of the first, second, and third-plus generations in 2011 from the 2017 NAS report. Figure 4 shows the same distribution as seen in 2017 in our update. Note that both Figures 3 and 4 use a three-year average, following the 2017 NAS methodology.

To restate the definition of immigrant groups, first-generation immigrants are foreign-born individuals excluding those granted citizenship at birth, the second generation have at least one foreign-born parent, and the third-plus generation are U.S. born persons without a foreign-born parent. Persons born in the U.S. territories, such as Puerto Rico and Guam, are also included in the third-plus generation. The 4.5 percent of people with one foreign-born parent and one native-born parent are split evenly between the second and third-plus generations using a random uniform distribution. This distribution credits an immigrant and native-born person who have a child together as each having one-half of the child, which is appropriate for NPV projections.34

The first generation is more heavily concentrated in the working ages (18–64) than the second- and third-plus-generation cohorts. The second generation has relatively more young persons and relatively fewer elderly persons. The paucity of persons who are of working age and elderly in the second generation is due to the recent liberalizations of U.S. immigration policy in 1965, 1986, and 1990 because not enough time has passed for many of their U.S.-born children to move into those age brackets.

The difference in the population structure in 2011 versus 2017 is slight, but demographic shifts are still apparent. The second generation ages into the working population throughout the sample. As the baby boomers retire, the third-plus generation is becoming more concentrated in the 65-plus age categories. The first-generation group remains young, and its population distribution in the coming years depends on future immigration policy. Those trends are briefly discussed in the next section, but a thorough discussion of the effect of demographic changes is beyond the scope of this paper.

The age structure of a population is central to understanding the fiscal impacts of the different generational groups at given points in time. If a population group is concentrated in the working ages, on average they pay more taxes than they receive in government benefits, so the group is likely to have a positive fiscal impact. Conversely, a population group that is skewed toward younger or older ages is likely to be receiving more in benefits than it is contributing in taxes and has a more negative fiscal impact. As we would expect, and as shown in Figures 3 and 4, the first generation has a more positive fiscal impact than the second and third-plus generations, and the second generation has a more negative fiscal impact than the third-plus generation. However, that relationship may change as the population structures shift over time. See the following section for a discussion about the age differences in tax payments.

Sometimes allocating the fiscal costs of children to their parents is appropriate. Although working-age adults typically pay more in taxes than they receive in government benefits, they also are more likely to be providing for dependents who impose public education costs on taxpayers. Combining children with parents allows us to compare the fiscal effects of families with different household sizes. Figure 5 shows that the first-generation immigrant households had a weighted average of 1.04 children per household aged 15–80—higher than the weighted averages of 0.71 and 0.63 for second- and third-plus-generation households, respectively. Immigrants have higher fertility rates on average and are more likely to live in multigenerational households. Also, as demonstrated in Figures 3 and 4, a larger proportion of the immigrant population is in the parenting age range.

Over time, as the immigrant population ages and if new immigrants continue to follow the trend of arriving at later ages, the number of children per immigrant household is expected to fall. Because young children carry high education costs, this change may make their fiscal impacts more positive over time.

Trends in Education, Employment, and Earnings by Immigrant Status

Education level is an important predictor of a person’s fiscal impact. Higher education levels are correlated with higher incomes and thus higher tax contributions. Furthermore, welfare benefits likely have an inverse relationship with educational attainment because more-educated individuals are less likely to qualify for means-tested welfare programs, but consumption of entitlement programs such as Social Security and Medicare increase with lifespan and earnings, both of which are positively correlated with education.

Figures 6 and 7 show the average educational attainment levels by immigrant group and age in 2013 and 2018, respectively. As shown in Figure 6, immigrants older than 25 had an average of 1.1 fewer years of education than native-born Americans in the same age range in 2013. In 2018, that gap was 0.9 years. Each immigrant group has similar levels of education when young due to mandatory schooling. Immigrants’ education departs from that of native-born Americans at age 20, and each immigrant group’s average education declines after age 40. Compared with the third-plus generation, the children of immigrants consistently earned higher levels of education. In 2013, the second generation had an average of 0.37 more years of education than the third-plus generation.

Education levels are lower at older ages in each figure, reflecting the rise in educational attainment over time. The upward trend in educational attainment is clear when comparing the education levels of older persons with their younger counterparts and the education distribution over time. In Figure 6, the average education level of a 70-year-old third-plus-generation native is roughly a year lower than that of a 30-year-old third-plus-generation native.

Figure 7 shows the average education attainment levels by immigration status in 2018. Immigrants continue to close the education gap and are only visibly distinguishable from native-born Americans after age 25. The second generation continues to obtain higher levels of education than their third-plus-generation counterparts, a trend that persists even as education levels rise for all generations. In 2018, the second generation had an average of 0.3 more years of education than the third-plus generation.

First-generation immigrants have made the largest educational strides since 1994, with average education for ages 25 and up increasing by 1.12 years between 1994 and 2018 (1994 not pictured). As education levels continue to rise, we expect that each generation will pay more in taxes, assuming that Congress does not radically change current tax policy. Increased taxes may translate to more-positive fiscal impacts, but old-age retirement programs and public school education costs combined with other benefits Americans receive over their lifetime may increase faster than tax receipts. We analyze those trends later in this paper.

Employment patterns have not changed considerably since 2013, the most recent year of data that the 2017 NAS analyzed.35 Figures 8 and 9 show the employment-to-population ratios by age for each immigrant group in 2013 and 2018, respectively. Figure 8 contains the expected n‑shape of employment, with immigrants having lower rates of employment in their early working years than the second and third generations. Between ages 20 and 40 in 2018, first-generation immigrants had an 11 percent lower employment-to-population ratio than the third-plus generation. This finding is partly the result of education differences because one more year of education is estimated to raise earnings by 9 percent and, hence, boost employment.36

In 2018, as education rates continued to rise for all cohorts, the employment gap closed. Shown in Figure 9, immigrants have a 5.1 percent lower employment-to-population ratio than native-born Americans in the second and third-plus generations, down from 6 percent in 2013. All immigrant groups saw an increase in their average employment-to-population ratio; for ages 18 to 65, the average rate increased by 4.4 percent.

The income differential between the second and first generations is higher than their differences in education levels would suggest. Figure 10 shows the wage and salary income by immigrant group in 2012 averaged over three years. Figure 11 shows the same relationship using 2017 data. During their working years of 18–65, first-generation immigrants earned an annual average of $31,271, the second generation earned an average of $40,255, and the third-plus generation earned an average of $36,830 in 2017. The differences between the second- and third-plus-generation wages may be related to chosen profession, state or city of residence, or other factors not analyzed here.

Similar to education trends, wages for all generations are increasing over time, and first-generation immigrants are catching up. Between 2013 and 2018, the gap between the first-generation and third-plus-generation income levels during their working years narrowed by $1,311 annually. If that trend continues, we expect that immigrants will continue to become more of a net fiscal benefit over time.

Trends in Fiscal Flows by Age and Immigrant Generation

We now examine the net fiscal impact of each age and immigrant generation cohort by comparing taxes paid and benefits received. This section allocates taxes and benefits to the person who incurs them. The next section redefines generational groups to include dependents (see Box 3) and explores the effect it has on fiscal flows. The rest of that section continues to look at the fiscal flows of individuals without including their dependents.

Figure 12 shows that the taxpayer cost of educating the young dominates the fiscal flows early in life; tax payment mostly dominates the middle years; and the cost of Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance and health care dominates in later years for all individuals regardless of generation and education. This temporal pattern holds for every age and generation with some variation. Changes in benefits consumed by each generation and education group between 2012 and 2017 are relatively small, but massive differences exist in the taxes paid by each group (see Figures 13 and 14). In both years, tax payments and benefit consumption closely track prime working ages and ages of benefit consumption. Immigrants aged 20 and older contributed about 25 percent less than the third-plus generation in 2017, down from 31 percent less in 2012. Members of the second generation aged 20 and older contributed 25 percent more on average than their first-generation parents in 2012 and 8 percent more in 2017. Per capita payments increased for both groups, whereas relative payments converged.

Tax contributions increased moderately over time relative to growth in earnings partly because of the TCJA, which was passed in 2017 but not implemented until later (see Figures 10–14). Between 2012 and 2017, per capita total tax payments rose by 13.5 percent for first-generation immigrants, 6.4 percent for the second generation, and 8.2 percent for the third-plus generation. By comparison, per capita consumption of government benefits rose slightly for the young in all generations, but little overall change occurred in the shape of the age profiles of benefits over time and across generations (see Figures 15 and 16). Figures 13–16 have the same y‑axes to allow for simple comparisons.

The third-plus generation consumes more benefits than the first and second generations at all ages older than typical years of college attendance.37 That result is unsurprising because the receipt of government benefits depends on the number of years an individual spends in the country, among other factors. Second-generation individuals use benefits at a higher rate than either first-generation immigrants or third-plus-generation natives until about age 25. From age 25 until the end of life, third-plus-generation individuals use means-tested welfare and entitlement programs more intensely than do the first and second generations (see Figure 16). First-generation immigrants at every education level never have the highest consumption of government benefits.

Figure 17 shows the same patterns of benefits use whereby the third-plus generation consumes more federal old-age benefits such as Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid payments to nursing homes, federal worker retirement, and other programs than do first-generation immigrants and the second generation for the years 2012 and 2017. In addition, the second generation consumes more federal old-age benefits than does the first-generation immigrant group. Figure 18 shows federal means-tested anti-poverty benefits received by generation and age, which includes programs such as Medicaid, Supplemental Security Income, unemployment insurance, food stamps, the earned-income tax credit, and other programs. First-generation immigrants typically receive fewer federal old-age benefits because they arrive in the country older and therefore earn fewer benefits. They tend to consume fewer federal means-tested welfare benefits until their early-to-mid-30s, after which they consume the most of any group.

Differences by generation in use of means-tested welfare and old-age benefits are partly legal and partly mechanical. Recent arrivals do not qualify for many of the means-tested anti-poverty programs, and many do not end up qualifying for the federal old-age benefits either (see Figures 16 and 17). However, program eligibility cannot explain differences in benefit use between the second and third-plus generations during their prime working years, so those differences are primarily driven by higher incomes and successful socioeconomic assimilation among the second generation. Figure 17 is also different from the corresponding figure in the 2017 NAS study. In that study, the first generation consumed many fewer means-tested anti-poverty benefits until about age 60 because Medicaid was allocated according to total per capita health expenditures, which includes Medicaid, Medicare, and other providers.38 More up-to-date Medicaid data allocated more benefit consumption to younger people, which changed the benefit consumption level by generation.

Figures 19 and 20 show the net fiscal impacts by age and generation for 2012 and 2017, respectively. These figures reveal that the second generation has a more positive net fiscal impact at almost every age than either the immigrant first generation or the third-plus generation. Individuals in the second generation pay considerably more in taxes during working ages and consume fewer benefits during their prime working years than do the other generations, although the second generation consumes more means-tested anti-poverty benefits at younger ages.39 Members of the third-plus generation contribute more in taxes than do first-generation immigrants, which leads to a more positive net fiscal flow during their prime working ages, but the trends switch once the individuals reach retirement age because the first generation consumes many fewer federal old-age benefits. The first generation consumes more means-tested anti-poverty programs in old age, such as Medicaid, but the cost of those programs is much lower than the cost of the old-age programs.

Figure 21 presents a counterfactual that assumes noncitizens in the United States have no access to means-tested welfare or entitlement programs, a policy environment similar to that introduced in a bill by Rep. Glenn Grothman (R‑WI) and first proposed by Alex Nowrasteh and Sophie Cole.40 Thus, Figure 21 does not show actual divergent net fiscal impacts, but it shows what the net fiscal impacts would be if noncitizens had zero access to means-tested welfare benefits and entitlements. Under those alternative welfare policies, noncitizens and citizens have a similar impact before age 18 because all have access to public schools. Noncitizens would consume about $4,000 less per year in welfare benefits than citizens aged 25–60. Beginning at age 63, citizen immigrants begin to have much more of a negative impact, whereas noncitizen immigrants barely drop below zero. If such a policy were enacted, then immigrants would react by changing their behavior—possibly by naturalizing at higher rates—but Figure 21 shows roughly how the net fiscal impact would adjust by age in at least the first year after enactment.

Annual Fiscal Impacts by Immigrant Status

This section considers the fiscal impact of different immigrant generations. We demonstrate that a generation’s size and age structure affect their net fiscal impact. Thus, aggregate fiscal impacts vary widely in magnitude, and comparisons of the net fiscal impact between generations are complicated. To address those issues, we present the net fiscal impacts of immigrant generations on an average per capita basis and as a ratio of taxes paid to the value of benefits received.41 When the fiscal ratio is greater than 1, the generation pays more in taxes than it receives in benefits. When the fiscal ratio is less than 1, the generation pays less in taxes than it receives in benefits. A fiscal ratio of 1 means that the generation pays exactly enough in taxes to cover the value of the benefits they consume. A major downside of the fiscal ratio approach is that it does not control for a generation’s age structure, which is vital to understanding the fiscal impacts of different subpopulations. Later in this paper, we will revisit controlling for age structure when comparing the fiscal impacts of native and non-native subgroups.42

Following the methods of the 2017 NAS report, we examine the annual fiscal impacts of all age cohorts of three broadly defined generations including dependents from the pooled March CPS data samples for the 1994–2018 period (see Boxes 1 and 3). Regrouping dependents in the second and third-plus generations with their first- and second-generation parental guardians, respectively, affects the third-plus generation by reducing the number of young children in that group while it increases the population for the first and second generations. The NAS’s rationale for that choice is to include the full fiscal cost of the immigrant because, as that report argues, the immigrant’s children would not be in the United States without the immigrant. That rationale is a poor justification because nearly all individuals in the United States would not be here today without an immigrant ancestor, but nobody would blame approximately 100 percent of the net fiscal impact of all people on immigration.

The flaws of the NAS’s reasoning were recognized by then president Donald Trump’s Department of Homeland Security (DHS) when it published a regulation restricting green cards to immigrants on the basis of estimates of their future use of benefits, the so-called public charge rule. When counting immigrant benefits for the purposes of a green card, the DHS wrote that “this final rule also clarifies that DHS will only consider public benefits received directly by the alien for the alien’s own benefit, or where the alien is a listed beneficiary of the public benefit. DHS will not consider public benefits received on behalf of another. DHS also will not attribute receipt of a public benefit by one or more members of the alien’s household to the alien unless the alien is also a listed beneficiary of the public benefit.”43 We interpret this as meaning that researchers must decide which benefits are consumed by immigrants and which are consumed by native-born Americans. The easiest and most reasonable means of allocating benefit use is to those who are the intended beneficiaries of the benefits. Thus, benefits collected by immigrants for their own consumption affect the fiscal impact of immigrants, and benefits collected for the consumption of their native-born children affect the fiscal impact of the second generation. To illustrate that point, workers in one generation may work harder, have higher incomes, and thus pay higher taxes if they have U.S.-born children, but researchers cannot allocate a portion of their incomes to the next generation. Thus, the simplest and most reasonable method is to separate fiscal impacts by generation and not by household.

Despite those problems, we followed the NAS methods and assigned dependent children to the parental generation if one or more independent parents were present in the household. That method raises the problem that a dependent could be associated with an independent person in a different generation, such as a child of a first-generation immigrant mother and a third-plus-generation immigrant father. To account for that possibility, we followed the NAS methods of randomly assigning one-half of the children to the mother’s generation and the other one-half to the father’s generation.44 If no parents are in the household, the generational group of the oldest coresident independent relative is assigned to the dependent, which assigns the fiscal costs of raising dependent children (which are mostly related to public education) to the generation of the relative raising the child. Dependent children of any generation obviously impose a net fiscal cost because they are likely consuming some benefits and are not working.

Table 2 reports subpopulation size for each generation, per capita fiscal impacts, and fiscal ratios for each generation and their dependents for different levels of government in 1994, 2013, and 2018. The numbers differ slightly for 1994 and 2013 relative to the 2017 NAS report because we adjusted for inflation and because updated past CPS data yield slightly different results. The cost of public goods is assigned on a marginal basis, as specified in Scenario 5 (see Box 2). We highlight Scenario 5 because we believe that it is the most realistic.45 We discuss the results for the alternative scenarios later. Table 2 reveals that the first generation and their dependent children have a higher fiscal ratio than either the second or third-plus generations, meaning that their tax payments are either greater than the value of the benefits they consume or closer to covering the fiscal costs. The first generation and their dependents pay more taxes to the federal government than the value of federal benefits that they consume, but they consume more in state/local benefits than they pay in taxes. The pattern is reversed for the second generation and the third-plus generations; their ratios are higher or the same for state/local receipts and benefits relative to the federal level. The difference is largely explained by education costs that are mostly born by state/local governments. Over time, the fiscal ratio for the second generation has improved from 1994 to 2018, whereas it has slightly worsened for the first and third-plus generations, likely due to their aging populations. Because the second generation is so young, the age distribution shifting toward working age in coming years will continue to improve its fiscal impact, and additional aging for the first and third-plus generations will continue to lower their fiscal ratios as more of them become elderly. Even so, the total ratio of 0.960 for the first generation and their dependents is significantly higher than the 0.741 and 0.747 ratios for the second and third-plus generations in 2018, respectively.

The numbers in Table 2 show large total fiscal shortfalls for all groups, as the ratio is less than 1.0. In 2018, the total fiscal shortfall for all levels of government for every generation is $1.348 trillion. The total fiscal burden is $31.2 billion for the first generation, $130.4 billion for the second generation, and $1.186 trillion for the third-plus generation. Each individual has an average fiscal shortfall of $507 in the first generation, $5,035 in the second generation, and $4,961 in the third-plus generation. The per capita fiscal shortfall for immigrants and their dependents overall is 9.8 times smaller than the fiscal shortfall for the third-plus generation. In other words, the first generation accounts for 18.8 percent of the population and a mere 2.3 percent of the deficit in 2018. The second generation accounts for 7.9 percent of the population and 9.7 percent of the deficit. The third-plus generation accounts for 73.3 percent of the population and 88 percent of the deficit.

Another way to compare differences between the generations is to divide the ratio of receipts to outlays for the first generation and their dependents by the ratio of receipts to outlays for the second and third-plus generations.46 This calculation is usually used to net out macroeconomic or structural factors between governments, such as the impact of recessions or military spending, but it can also be used to compare the fiscal impact of different generations or other subgroups inside the same country. The ratio of the ratios for the first generation to the second generation for total expenditures is 1.3, which shows that the first generation has a 30 percent better impact on all government finances in the United States compared with the second generation. The ratio of the ratios for the first generation to the third-plus generation for total expenditures is 1.28, which shows that the first generation has a 28 percent better impact on all government finances in the United States compared with the third generation.

We cross-checked the numbers in Table 2 against the National Income and Product Accounts (NIPA) figures for the actual federal and state/local budgets combined in 2018. According to the NIPA, the tax payments were $4.624 trillion and total expenditures were $6.031 trillion, with a total deficit of $1.407 trillion. The consolidated deficit for 2018 was larger according to NIPA than under our calculations by $59.2 billion because NIPA recorded slightly higher expenditures and tax receipts.

Figure 22 plots the total fiscal ratio of receipts to outlays for the three generational groups, as defined in Table 2, across all years since 1994. No correction has been made in Figure 22 or in Table 2 for different age distributions across groups or over time. The net fiscal impact of all groups rose during the economic boom of the late 1990s, rose again from the trough of the Great Recession, and then rose again to a peak around the time of the passage of the TCJA and spending expansion of the early Trump administration. Each new peak coincides with a period of economic expansion, but each subsequent peak and trough is below the earlier peak and trough, showing the overall worsening fiscal trend for all groups.

Table 3 shows the per capita receipts-to-outlays ratios for each alternative scenario defined in Box 2 and the eight estimates under the eight different scenarios, including Scenario 5, which was presented in Table 1.47 To reiterate, Scenarios 5 through 8 assume the marginal cost allocation of public goods and Scenarios 1 through 4 include the average cost scenarios. For Scenarios 5 through 8, the marginal cost allocation of public goods is applied to all members of the first-generation group, which includes their second-generation dependent children. Scenarios 5 through 8 are the most realistic estimates because the U.S. government would supply public goods even if the immigrant population were zero. Table 3 also shows a much more favorable fiscal cost estimate—which it mathematically must. For Scenarios 5 through 8, the first generation has a ratio of federal receipts to outlays of more than 1, meaning that they pay more in taxes to the federal government than they consume in benefits, and they have a more positive net fiscal impact than that of the second and third-plus generations. The first generation’s ratios of receipts to outlays for the state/local governments are less than 1 and generally worse or similar to the ratios of receipts to outlays of the second and third-plus generations. When federal and state/local receipts and outlays are combined, the first generation has a more positive fiscal impact in every scenario, but the ratios of receipts to outlays is still less than 1.

The biggest differences across the scenarios in Table 3 are the ways that government spending on public goods, such as national defense and interest payments, are allocated. Government expenditures on public goods are large at the federal level: Defense outlays were $568.3 billion, federal interest payments were $481.3 billion, and subsidies and grants accounted for another $55.8 billion in 2018. Those spending categories account for about 35 percent of total federal outlays in that year, according to NIPA. Because those public goods would exist without any immigrants, and because the presence of the first generation does not increase defense budgets or interest payments, Scenarios 5 through 8 allocate all their costs to the second and third-plus generations, which significantly changes the estimates. Allocating the average cost of public goods across all generations lowers the receipts-to-outlays ratio for the first generation to be much closer to the ratios for the second and third-plus generations in Scenarios 1 through 4. Therefore, the marginal-cost versus average-cost assumptions in the scenarios in Table 3 are extremely important in driving estimates of the fiscal impact in different generations.48

The results vary in the other scenarios in Table 3, but the variations are small compared with the choice between marginal cost and average cost for public goods. Scenarios 3, 4, 7, and 8 adjust the first generation’s tax contribution downward in different ways on the basis of immigrant spending patterns and investment decisions. Those choices reduce receipts, but the reductions are small compared with the scenarios that differ on marginal-cost and average-cost allocations.

Comparing Immigrants with Natives, Controlling for Characteristics

The per capita net fiscal impacts and fiscal ratios reported previously are associated with broad groups of individuals with widely varying ages and other characteristics. Net fiscal impacts of the first-generation group are shaped largely by their disproportionate age distribution in the working-age and family-rearing portion of the life cycle. In the aggregate, they make lower per capita tax payments while consuming a moderate amount of per capita benefits compared with other generations (see Figures 14 and 16). As today’s immigrants age, their children continue to move out of their parents’ households, and as the immigrants retire, their fiscal profiles will dramatically change.

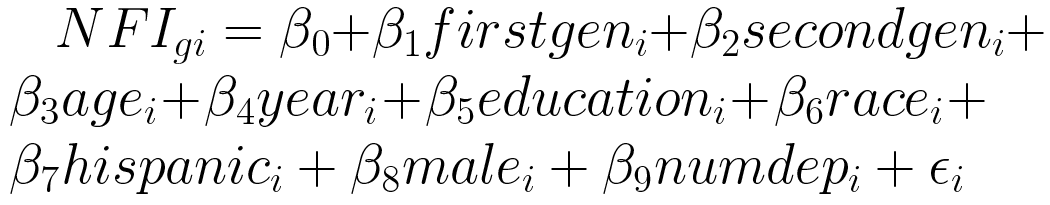

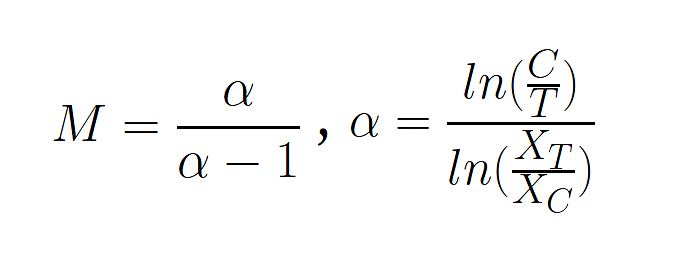

Table 4 shows how net fiscal impacts correlate with immigrant-native differences in characteristics of the pooled March CPS samples spanning 1994 to 2018. As in Table 2, each generation includes their dependent children, which pairs the taxpaying parents with their benefits-consuming children. Table 4 uses the estimated fiscal impacts for the third-plus generation as the benchmark group for a regression analysis of how the first- and second-generation groups differ from this benchmark. The unit of analysis in the regression in Table 4 is the independent individual, which shrinks the sample size significantly. In other words, the flow of benefit outlays and tax receipts for dependents is rolled into the flows of the independent person to whom they are linked in the data, allowing us to estimate the impact of independent persons depending upon various demographic variables. The basic regression equation is as follows:

NFI is the individual’s (i) net fiscal impact at the level of government (g); firstgen and secondgen are dummy variables indicating the individual’s immigrant generation; age, year, education, and race are fixed effects for each respective categorical variable; hispanic is a dummy variable indicating Hispanic ethnicity; male is a gender dummy; numdep is the number of dependents the individual has; and ε is an error term. The results are in Table 4.

Table 4 has five models that regress the first and second generations on the third-plus generation. Each has different controls with successively numbered models, including additional control variables that are bolded. The results of every regression are statistically significant.

Model 1 in Table 4 shows the differences in net fiscal impacts of the first and second generations relative to the third-plus generation without any controls. The first generation’s net fiscal impact is $909 less per independent person at the federal level and $1,920 less at the state/local level for a total of $2,829 less in net fiscal impact per independent person overall. The corresponding estimates for the second generation are $2,857 less per person at the federal level, $355 more per person at the state/local level, and $2,502 less in total. The big differences in Model 1 for the second generation compared with Figures 19 and 20 are likely due to age differences that are partly unaccounted for in the simple regression without controls.

Model 2 in Table 4 adds controls for age, calendar year, and sex to produce a more reasonable comparison. In Model 2, a negative coefficient means that the net fiscal impact is more negative for a member of that generation than for a member of the third-plus-generation reference group, controlling for age, year, and sex. A positive coefficient means that the net fiscal impact is more positive for a member of that generation than for a member of the third-plus-generation reference group with the same controls. Relative to Model 1, those controls in Model 2 produce positive coefficients for the second generation for every regression while making the coefficients for the first generation even more negative compared with the third-plus generation.

Models 3, 4, and 5 add more controls sequentially for education, race and ethnicity, and the number of dependents, respectively. Model 4 produces the most positive net fiscal estimates for the second generation. Each successive model produces lower negative estimates of the net fiscal impacts or more positive estimates for the first generation. An unsurprising finding is that controlling for education, race and ethnicity, and the number of dependents eliminates a significant portion of the net fiscal impact for the first generation because systematic differences in those demographic factors have a large impact on the net fiscal impacts. Taken together with the findings in Tables 2 and 3, the regression results from Table 4 show that the assignment of marginal or average fiscal costs to immigrants and demographic controls have an enormous impact on the final estimates.

Forecasts of Net Fiscal Impacts under the Updated Model

The previous section examined the fiscal impacts of immigrants and other generations over recent decades using current and historical data. The findings in that section revealed that recent fiscal impacts reflect the relative youth of today’s immigrants and thus may not indicate their future impact on U.S. budgets and taxpayers. The important questions to answer are as follows: If an immigrant arrives in the United States, receives benefits, and pays taxes over the course of his or her lifetime, will that immigrant’s net contribution to public finances be positive or negative?49 Will the children of the immigrant who consumes government benefits today pay enough taxes in future years to make up for today’s cost? What is the magnitude of the total new contributions or costs associated with the immigrant’s arrival and the life of their descendants? If the net fiscal impact is negative, how much would benefits need to be reduced to make the immigrant’s net fiscal impact neutral?

To answer those questions, this section projects the future impacts of immigrants using a method called generational accounting to predict the fiscal impact of immigrants on the budgets at the state/local and federal levels over the following 30 years. Generational accounting is the best method for estimating how immigrants, on average, affect government finances over the life cycles of the immigrants, which is important because government spending and taxpayer payments vary significantly over the life cycle of the individual. When young, individuals consume means-tested welfare benefits and public education. During their working years, they consume some means-tested welfare benefits but mostly pay taxes. In their elderly years, they primarily consume entitlement and means-tested benefits. This method assumes the condition and subsequent life experience of an average new immigrant on the basis of the characteristics of recent arrivals, projects that immigrant’s behavior into the future, adds tax payments and benefit receipts each year, and weights that amount by the probability of remaining in the United States and surviving. In addition, the model forecasts the fertility of and taxes paid by immigrant parents and benefits received by their children that are then weighted by their probability of emigration and survival.

Projections of net fiscal impacts require assumptions about future economic and fiscal developments that are uncertain. Thus, the predictions and estimates in this paper should be read with that fact in mind. The CBO routinely predicts government outlays and tax receipts—with a poor record of accuracy.50 Nevertheless, estimates of future fiscal outlays and taxes are essential to creating a generational accounting model to evaluate the net fiscal impact of immigrants and their descendants. We also included an array of different CBO budget projections that were also included by the NAS in its 2017 report. Those different budget scenarios can inform a broad range of fiscal impact projections.

The Future in Context

The demographics of immigrants and native-born Americans have changed since the NAS published its report in 2017. Similarly, government budgets on both the state/local level and the federal level have also changed since the NAS published its 2017 report. Those changes affect the estimates of the net fiscal impact of all immigrants and more-recent immigrants.

Recent Immigrants

Immigrants have characteristics that affect the amount of taxes they pay and the value of benefits they consume. The figures that follow focus on the levels of education, age of arrival, and time since arrival, as those factors have a bearing on the benefits they receive and the taxes they pay. Education level is correlated with current and future earnings, which in turn affects tax payments. For instance, more-educated workers typically have higher earnings that result in higher tax payments. Those earnings also determine eligibility for means-tested benefits, unemployment insurance, and entitlement benefits, all of which are based on past earnings. Age of arrival determines where an individual falls on the n‑shaped earnings curve and on the u‑shaped benefits-consumption curve. Time since arrival affects the net fiscal estimates in at least three ways. First, time in the United States affects legal eligibility for benefits. Second, time in the country correlates with the extent of wage assimilation.51 Third, age of arrival separates different arrival cohorts with different characteristics correlated with tax and benefit flows.

To accurately estimate how the fiscal impacts of today’s immigrants might continue to change over time, it is necessary to identify the characteristics of recent immigrants and of the overall immigrant stock. Table 5 shows recent arrivals and the stock of immigrants by their level of education. Recent arrivals are in the top panel of Table 5, and the stock of all immigrants is in the bottom panel. Table 5 shows standardized measures of those educational distributions that are obtained by applying age-specific education rates for different groups to the age profile of first-generation immigrants.

Recent immigrants who arrived in the 2016–2018 period are more highly educated than those who arrived in the 2011–2013 period. For instance, 17 percent of those who arrived in the later period have less than a high school degree, compared with 22 percent of those who arrived in the earlier period. Similarly, the percentage of new arrivals with a college degree and those with more than a college degree increased by about 3 percentage points and 4 percentage points, respectively, from the earlier to the later period. More of the recent immigrants in the 2016–2018 period are in the higher-earning and higher-taxpaying educational groups, whereas fewer are in the lower-earning and high-benefit-consuming educational groups, compared with the 2011–2013 period. By comparison, the second and third-plus generations also increased their levels of education but to a smaller degree.

The first generation has a u‑shaped education distribution, with more persons who have less than a high school degree and more with a college degree or higher. By comparison, the second and third-plus generations have n‑shaped educational distributions, with more people in the middle and fewer with lower and higher levels of education.

New Immigrant Current Tax Payments and Benefit Receipts

A key challenge in estimating the forward-looking fiscal net impacts of immigrants is dealing with the incomplete educational histories of young immigrants who have not yet completed their education. That fact is important because educational attainment has significant impacts on individuals’ tax payments and welfare receipts. To address that complication, we followed the NAS’s 2017 method of estimating the future educational levels of individuals as a function of their parents’ education and birthplace groups, as summarized in the methodology section.52

Our first step was examining age profiles of wage and salary earnings in Figure 23. A clear gradient in earnings by education emerged that is broadly similar for each generation.

Figure 24 shows the net fiscal impact by educational attainment and generation in 2017, with persons younger than 25 with incomplete educations coded as having the education of a parent or an average level of their parents’ education if they have two parents. We coded only the education of people younger than 25 that way to make our estimates comparable with the NAS report. That coding is different in the Cato Model. The net fiscal impact for persons in all generations and education groups starts out as sharply negative, largely due to consumption of public school, and then rises rapidly after age 18. The net fiscal impact of those who finish high school then rises sharply beginning around graduation age, relative to high school dropouts. Net fiscal impacts rise strongly and become positive during the prime working years except for third-plus-generation high school dropouts, who have hardly any years when they have been net taxpayers. In other words, high school dropouts in the first and second generations have a positive fiscal impact during their working years, whereas third-plus-generation dropouts contribute more in taxes for just a handful of years, if that. Third-plus-generation dropouts consume more benefits than either of the other groups. First-generation consumption of benefits is legally limited because access to benefits is determined by immigration status and time in the United States, resulting in many immigrants who do not have access to most benefits for several years, if ever.53 The most interesting finding is that the second generation has a net fiscal impact closer to that of the first generation than that of the third-plus generation even though the second generation has access to all benefits programs.

Immigrant tax contributions rise strongly with education. Figure 25 normalizes the high school dropout tax contribution to 1 for each year and for each level of government. Each successive level of education shows sharp increases in tax payment by education. For example, in 2017, total taxes paid by immigrants with more than a college degree are more than four times higher than total taxes paid by an immigrant who is a high school dropout. The changes are small from 2012 to 2017 for state/local governments, but the changes are larger for federal taxes, which show slight declines due to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017. The reduction in tax payments from the TCJA shows up here because the tax cuts went into effect on January 1, 2018, and the results in Figure 25 are pooled samples during the 2016–2018 period, which includes one year when the TCJA was in effect. The trends for immigrants in Figure 25 are very similar to the trends for the average person in the second and third-plus generations. The relative changes in benefit receipts are more similar across education groups than they are for tax payments, with slight relative changes since 2012. The largest change in benefit receipts recorded in Table 6 was for retirement-age individuals in the second generation, who experienced a 34.8 percent increase in benefits on the state/local level. Note that for ages 65 and older, the second generation’s state and local benefit values are sensitive to random generational assignment of the 2.5 generation,54 which is expected given how few elderly second-generation individuals are in our data.55 The second generation was randomized into the second and third generations and includes those who have one immigrant parent and one native-born parent.

Tax Payments and Benefit Receipts by Additional Immigrants and Their Descendants in the Future

Predicting the eventual taxes paid and benefits received for an average immigrant and their descendants requires forecasting the ultimate educational attainment of young immigrants and the future education level of offspring. As stated, we followed the 2017 NAS method for the Updated Model, whereby we predicted the education of offspring as a function of parental education using regression analysis based on CPS samples 15 years apart.56 The sample from 15 years ago gave the educational levels for immigrant parents from a given region of the world who have coresident children aged 10–16. The later sample gives education levels for people aged 25–31 whose parents were born in that region. We regressed adult education on parent education by birth region, with separate equations for native-born children versus foreign-born children. Following the 2017 NAS’s method, we then used the regression results and included a random error term to predict the child’s ultimate educational attainment. The random error term was used to obtain more-realistic variation in educational distributions for each generation. Again, following the 2017 NAS’s method, we used separate regressions to estimate the transmission of educational attainment from foreign-born parents to foreign-born children and, for comparative purposes, the educational transmission from U.S.-born parents to their U.S.-born children.