I will try to make my comments broadly applicable to any recent year, but it is impossible to ignore how the past year has seen the meager legal immigration system become more closed than at any point since the end of the Great Depression.1

“Why Don’t They Just Get in Line?” Barriers to Legal Immigration

[I]t is impossible to ignore how the past year has seen the meager legal immigration system become more closed than at any point since the end of the Great Depression.

Subcommittee on Immigration and Border Security

Committee on the Judiciary

United States House of Representatives

Chair Lofgren, Ranking Member McClintock, and distinguished members of the subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to testify.

My name is David Bier. I am the research fellow for immigration studies at the Cato Institute, a nonpartisan public policy research organization here in Washington, D.C. Having worked for a then-member and vice chair and later the chairman of this important subcommittee, it is an honor to be invited back to share my perspective on the challenges that America’s legal immigration system faces. My perspective is informed, in part, by the multi-year effort we made to study and propose bipartisan reforms during that time. Unfortunately, the failure to act then has only further exposed the underlying flaws in our broken immigration system.

The Framework of U.S. Immigration Law

The simple answer to the question that this hearing poses — why don’t immigrants get in line? — is that immigrants cannot legally get into “the line” — that is, apply for legal permanent residence on their own. To the extent that the U.S. government allows legal immigration, it is based almost exclusively on selection or sponsorship by the U.S. government or U.S. families, employers, or other sponsors. Thus, the question could be restated: why can’t Americans let immigrants get into “the line”? The answer to this question is that the government effectively bans them from doing so.

It is important to start with the basic legal framework for U.S. immigration. Unlike most other areas of law familiar to Americans, all immigration is presumptively illegal unless immigrants prove that they fall within a few narrow exceptions based on U.S. sponsorship or selection, and most exceptions have hard numerical limits.2 This legal state is most similar to the status of alcohol sales under Prohibition where sales were generally illegal with certain allowances for industrial, religious, or medicinal purposes.

Prior to the 1920s, the legal framework was reversed: nearly all immigration was presumptively legal unless the government found that an immigrant fell within a category specifically barred.3 Today, the only immigrants who can immigrate permanently from abroad without numerical limits are the spouses, minor children, and parents of adult U.S. citizens,4 and even they have more potential bars to obtaining legal permanent residence than ever.5

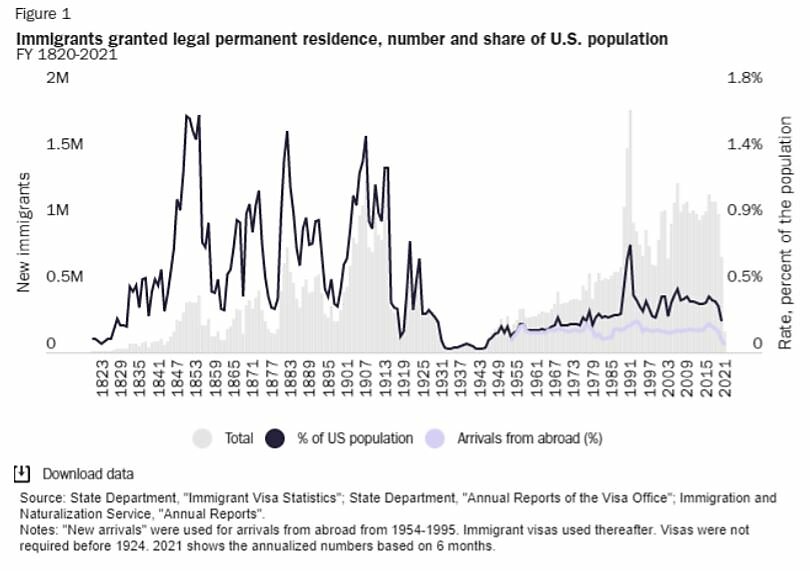

The result is that the United States has allowed a much lower rate of permanent legal immigration as a percentage of its population than in the years before the Immigration Act of 1924 (Figure 1).6 On average, from 1820 — when the records begin — to 1924, the country allowed an average annual rate of immigration equal to about 2/3 of a percent of its population. This would be the equivalent of nearly 2.2 million people today, triple the number of new legal permanent residents in 2020, and more than double any year in the last decade.

In several years before 1925, the rate hit 1.5 percent of the population, which today would be nearly 5 million immigrants. In 2019, the rate had fallen 80 percent from those peaks, and it has plummeted even lower since the pandemic. Moreover, more than half of new immigrants in recent years have adjusted to permanent residence after they had already entered the United States either illegally or with temporary statuses, meaning that the rate of new immigrants from abroad is lower still.7

Controlling for the size of the country, the United States also allows comparatively few immigrants to come — legally or illegally. The United States ranks in the bottom third of wealthy countries for the share of its population that is foreign-born as well as in the bottom third for net per capita increase in foreign-born residents.8 This is despite the fact that no country has such a large share of its population in the country illegally. For refugee intake per capita, the United States is outside of the top 50 countries in the world,9 and for per-capita employment-based immigration, the United States lags behind nearly all the developed countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).10

Documented Immigration

Today’s highly restrictive system leads to violations of the law by immigrants whom it disqualifies, lengthy wait times for those who do qualify, and lost benefits to Americans who wish to associate with both.

Consider the only current options to immigrate to the United States permanently from abroad for someone without a parent, spouse, or adult child who is a U.S. citizen — the only uncapped immigration categories:

1. The diversity visa lottery: The diversity lottery program is the only immigration category under which people apply directly and, in theory, don’t need a sponsor and don’t need a college degree, though in practice the rules make it very difficult to qualify without a college degree or an employer lined up.11 In recent years, the program averaged more than 20 million applicants, and an average of just 50,000 received a visa, which is just a 0.2 percent annual chance — a chance that has actually fallen by more than 80 percent since the lottery started in 1994.12 As importantly, only people born in countries from which few immigrants have come in recent years can participate, meaning that immigrants from the top four origin countries for undocumented immigration — Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, and El Salvador — are all currently excluded.13

2. The U.S. refugee program: Since it started in 1980, the U.S. refugee admissions program has allowed a narrow class of people with a well-founded fear of persecution based on certain protected grounds to immigrate.14 Over the last decade, refugees had about a 0.4 percent annual chance of being selected for the refugee program — a rate which has also declined by more than 80 percent since 1980 — and there is also generally no way to apply directly.15 Refugees must generally obtain a referral from the United Nations, a U.S. agency, or designated nonprofits, and usually they must have already left their home country.16 So far in 2021, the program has resettled six refugees born in the top four origin countries for undocumented migration.17

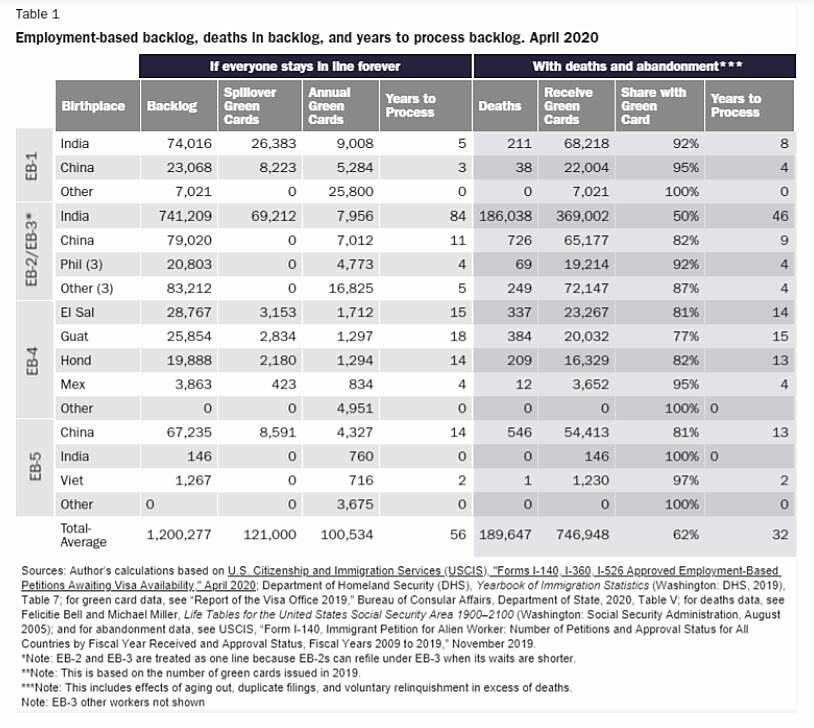

3. Employer sponsorship: Employers may sponsor their employees, but their employees have a hard annual numerical limit of 130,000 green cards — half of which go to the spouses and minor children of the workers.18 This limit was last updated in 1990. Immigrants from a single birthplace can obtain no more than 7 percent of the green cards in a single year unless they would otherwise not be used.19 Since India-born immigrants make up about half of all the employer-sponsored immigrants, a massive backlog of about 800,000 applicants from India has developed.20

Before the pandemic, this backlog was growing at a rate of more than 10,000 applicants per month. Indians who are receiving green cards right now typically waited 10 years, but assuming no change in the rate of issuances, it will take — for anyone applying tomorrow with a master’s degree or less — at least 84 years for them to receive an employersponsored green card.21 Even if they could theoretically stay in line for that long, nearly 200,000 Indians in the backlog will certainly die before they could even theoretically become permanent residents (Table 1).22 In addition, roughly 100,000 of the minor children of the workers currently in line will age out and lose eligibility for permanent residence under their parent’s employer sponsorship when they turn 21 — nearly 10,000 this year.23

The only reason that some employers are willing to suffer through even the current 10 years for Indians is that nearly all the college-educated workers receiving permanent residence through the employer-sponsored system are already in the United States working for them on renewable work visas like the H‑1B visa.24 But for workers without a college degree — like nearly all workers crossing the border illegally — it is virtually impossible to obtain an employer sponsor for a green card because there is no work visa for year-round jobs that would allow them to enter and go through the permanent residence process in the United States. Employers generally have to rely on one of the meager 10,000 permanent immigrant visas allowed for workers without a college degree.25

Even if the worker is not from India and could theoretically immediately receive a visa under the caps, the bureaucratic process for obtaining one of these 10,000 immigrant visas makes them entirely unusable for employers. The Department of Labor, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, and Department of State collectively take more than 2 years to process an employer-sponsored immigrant visa.26 Employers cannot justify expending the time and money over the course of two years for workers who aren’t already working for them. Each one of these agencies during the two years could deny the employer or worker, and all the costs would be for nothing. Even if approved, the worker might end up leaving as soon as they come, requiring the employer to duplicate the 2‑year procedure.

Meanwhile, these exact same agencies take as little as 60 days to process seasonal farm workers under the H‑2A guest worker program, despite effectively the same requirements in the law.27 For this reason, these temporary worker programs have become virtually the only way for non-college educated workers to come to the United States legally, but when they are here, employers cannot sponsor them for permanent residence because the regulations require that the job be permanent, not temporary or seasonal.28 This leaves effectively no option for immigrants without college degrees to be sponsored for permanent residence by their employers.

The only other employment-based option to immigrate permanently is for 10,000 investors and their families who can afford to invest between $900,000 and $1.9 million in a U.S. business that creates 10 new jobs.29

4. Other family sponsorship: Aside from spouses, minor children, and parents of adult U.S. citizens who are exempt from the caps, U.S. citizens and legal permanent residents can theoretically sponsor certain other immediate family members (and their spouses and minor children). But except for spouses and minor children of legal permanent residents, the wait times have effectively closed certain categories to new applicants. For instance, the minimum wait for a U.S. citizen applying now for their brother or adult married child is 23- 25 years, but as a result of the 7 percent per country caps, the wait for Mexicans will be nearly a century during which time nearly 400,000 applicants will likely die.30 A nonMexican adult child of a U.S. citizen has a bizarre incentive not to marry their spouse until after they receive a green card because the wait time for unmarried adult children is “just” 7 years, and once they receive a green card, they can sponsor their spouse in just over two more years, compared to 23 years if they married beforehand.

The exceptions to the presumptive ban on legal immigration ultimately provide very few options for immigrants to immigrate permanently. The options that do exist are so constrained that they provide hardly anyone considering migrating illegally a legal chance to come.

Undocumented Migration

Undocumented immigration is a black market in human movement. Black markets are the inevitable and predictable result of government prohibition. For this reason, the earliest undocumented immigration in the 1920s was often called “bootlegging in people,” making a rhetorical tie to the then-pervasive black market in alcohol.31 People at the time immediately understood that border crossers, boat jumpers, and visa overstays were all outcomes from the government’s effort to drastically restrict legal immigration.

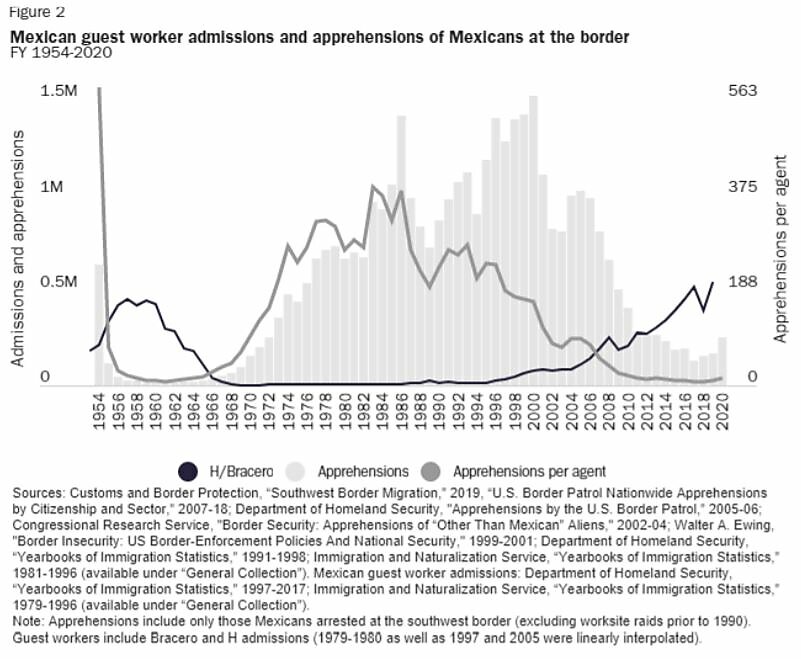

Black markets can be greatly reduced when the costs of following the law fall below the likely costs of violating it. In the 1950s and 1960s, the government largely controlled undocumented immigration from Mexico by directing border crossers into the Bracero guest worker program, which allowed workers to obtain legal contracts with U.S. farmers.32 While the program failed to protect the rights of workers as well as it could have, it lowered the costs of following the law below the expected costs of crossing illegally for most Mexican workers, greatly reducing the size of the black market. Unfortunately, Congress simply ended the program in 1965. Once it became that no legal channels were going to replace it, undocumented immigration surged to unprecedented highs in the 1970s and remained high for nearly three decades.

In the late 1990s, however, as Border Patrol made crossings more difficult, employers turned to Mexican guest workers again under the H‑2A and H‑2B visa programs, which corresponded with a sustained drop in apprehensions of Mexicans at the border (Figure 2). One of the first Mexicans to be hired as an H‑2A worker, José Vásquez Cabrera, told the New York Times that he jumped at the opportunity because, he said, with a visa, “I no longer have to risk my life to support my family. And when I’m here, I don’t have to live in hiding.“33

Based on the number of arrests for the average Border Patrol agent,1 each agent averaged nearly 97 percent fewer apprehensions of Mexicans at the border since 2010 than during the 1980s — 11 per year versus 299 per year (Figure 2). Mexican undocumented immigration fell further and faster than the increase in guest worker admissions. Jose Bacilio, a former-H-2A worker, explained why to the Washington Post in April 2019.34 He said, even though he had not yet received a visa that year, he wouldn’t risk all of his future chances by crossing illegally.

From 2000 to 2018, a statistical analysis conducted by my colleagues estimates that 3 additional guestworker visas from Mexican workers reduced the number of Mexicans apprehended at the border by 2.35 More research needs to be done on this topic, but there is a clear relationship whereby more legal visas for Mexicans reduces unauthorized Mexican entries. While highly successful in preventing illegal crossings, the H‑2B program for nonagricultural seasonal workers is not as effective as it could be because — unlike the H‑2A program for farms — it has an arbitrary cap that was last permanently updated in 1990.36

Even as border crossings were declining in the late 1990s and early 2000s, however, the undocumented population from Mexico continued to grow until 2007. The primary cause of this continued increase was that H‑2 visas were still not yet prevalent enough to deter most undocumented crossers, and increased border security had increased the cost of crossing illegally to such an extent that it made departures and reentries every growing season too expensive to justify. Prior to the hardened border, the vast majority of undocumented immigrants left within a year. By 2009, nearly none did.37 The end of this circular migration meant that workers who entered ended up staying permanently and spreading across the country, increasing the undocumented population.

Congress exacerbated the growing problem of permanent undocumented settlement in 1996. For many years, undocumented immigrants have generally been barred from adjusting to permanent residence if they crossed the border illegally, requiring them to go home, obtain a visa, and return. In 1996, however, Congress barred anyone with at least 180 days of illegal presence from leaving and reentering legally for 3 years and anyone with at least a year of illegal presence for 10 years.38

Known as the three- and ten-year bars, these barriers to illegal immigration make it impossible even for the 1.2 million undocumented immigrants who would immediately qualify for permanent residence to leave and reenter legally — effectively cutting them off from the “line.“39 Similarly, those deported from the United States face a permanent bar on returning legally, once again cutting untold thousands of parents of U.S. citizens off from their children north of the border.40 Inevitably, tens of thousands of Border Patrol’s apprehensions each year come from stopping parents of U.S. citizens seeking to reunite with their families.41

In recent years, as Mexican migration has declined, Central American migration has risen to constitute the majority of Border Patrol arrests since 2014.42 But Central Americans have not benefited from the boon in H‑2 visas because employers rarely have any economic incentive to hire from anywhere further away than Mexico. Instead, Central Americans come and work in occupations that are not eligible for an H‑2 visa: year-round positions in meat processing and packing, dairies, construction, and other industries. This situation helps highlight the most important fact about U.S. immigration law: immigrants cannot “get in line” to obtain work visas. Rather, U.S. sponsors must first request that they receive visas. If Congress wants Central Americans to receive work visas, it must create entirely new programs or specifically require H‑2 employers to hire Central Americans.43

Consequences

The consequences of the highly constrained legal immigration system are too numerous to list. The government’s enforcement efforts against undocumented immigrants impose a significant cost on taxpayers and U.S. citizens wrongly caught up in those efforts. American families are separated, either through deportation or through exclusion. U.S. citizen children face the prospect of losing a parent or spouse who lacks legal status. The United States loses millions of potential citizens and legal residents who could contribute to keeping America the strongest and most influential country in the world.

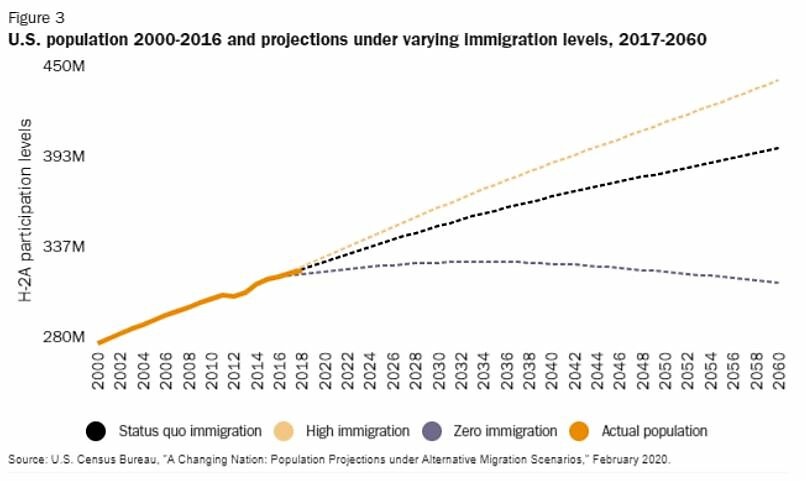

The economic consequences are severe. Without immigration, the U.S. population will age and decline (Figure 3), causing great strain on public resources.44 Population decline is already affecting three quarters of America’s rural counties.45 Research has shown that the limits on skilled immigration have pushed more companies to move offshore.46 Economist Charles Jones found that the increase in the share of scientists and engineers in the U.S. workforce can explain about half of U.S. growth in total factor productivity in recent decades,47 and about 80 percent of that increase came from immigrants.48

Skilled immigrants on H‑1B visas trapped in the green card backlog cannot start businesses or easily shift job categories. Currently, many H‑1B workers’ spouses and children cannot work, and even when they should be able to, in theory, the bureaucracy is currently making almost impossible to do so.49 Trapping workers in less productive positions or out of the workforce entirely means that the United States is passing on massive economic gains. Blocking workers from coming and sending workers back to India has allowed that country to surpass the United States in software exports.50

Immigrants are already twice as likely to start a new business as U.S.-born Americans.51 Yet the government has no way for entrepreneurs to enter the country for that purpose, and H1B workers are effectively barred from self-sponsoring for visas or green cards as entrepreneurs, making the lengthy waits for green cards particularly damaging to the economy. Of the patents at the top 10 patent producing universities in 2011, 76 percent had at least one foreign-born inventor or co-inventor, including 79 percent of pharmaceutical drugs or drug compounds.52 With visa restrictions, the United States is losing these inventors to other countries. From 2016 to 2019, the number of Indian immigrants going to Canada more than doubled, many coming straight from the United States.53

Despite advancements in automation and increasing demand for higher skilled workers, the Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts that in 2026, 73 percent of U.S. jobs will still not require a 4‑year college degree or equivalent training, including 62 percent of the job growth.54 These jobs include physical therapist assistants, home health aides, personal care aides, which will increase in importance in the next ten years as the population ages.55 In fact, nearly half of the fastest growing jobs do not require a 4‑year degree.56 Economists have generally found that the immigration of workers with less education has improved working conditions for similar U.S. workers.57 Because these immigrants work in complementary positions to workers with more education, they have also increased the demand for higher skilled workers and so increased the rewards to education, which has led a greater number of U.S.-born Americans to stay in school.58 Restrictions on lower skilled immigration will undermine Americans’ transition toward a skilled labor force.

Conclusion

The legal immigration system is effectively closed off for most potential immigrants to this country, and very difficult even for those few who do qualify. To address illegal immigration and to protect the U.S. economy, Congress should make legal immigration much easier than it is today. It should start by removing the per country limits for employment- and family-based immigration that discriminate based on birthplace, but ultimately, it should remove the worldwide limits on family- and employment-based immigration, which only serve to separate U.S. families and undermine economic growth. In lieu of this, it should cap wait times at no more than five years, and it should create a temporary work visa program for year-round jobs not requiring a college degree. It should remove the three- and ten-year bars and allow immigrants to correct their status by traveling abroad and applying for visas.

Until America returns to its historic practice of allowing immigrants to reside legally, it will suffer the economic and social penalties that come from illegal immigration.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.