Over many decades, the Cato Institute has produced original research on the benefits of immigration to Americans, the problems of illegal immigration and chaos along the southwest border caused by the restrictive legal U.S. immigration system, and sober evaluations of the realistic hazard of foreign-born terrorism. In my research, I use a broad definition of terrorism: the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by non-state actors to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation.1 Drug cartels and other criminal organizations are not terrorists even though those other criminals engage in heinous crimes, commit far more murders, destroy much more property, and injure more innocent people. Terrorism is not synonymous with “bad crimes.” It is a specific type of crime based on the motivations of the criminal.

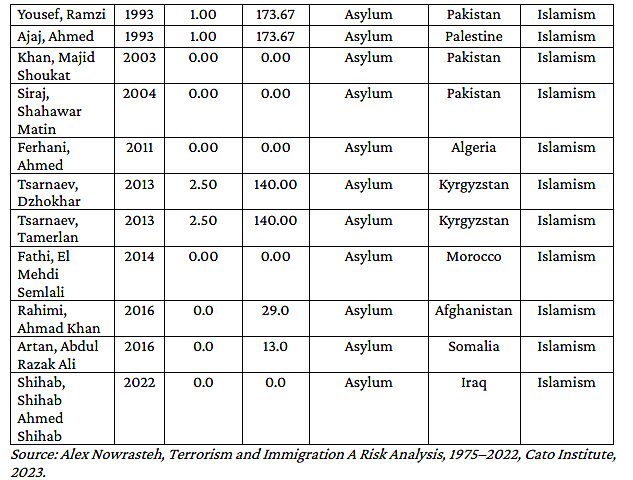

Foreign-born terrorists seeking to commit attacks on U.S. soil pose a hazard to the life, liberty, and private property of Americans and the lawful operation of the U.S. government. Reducing the risk of foreign-born terrorism is a legitimate function of the U.S. government. Nonetheless, terrorism committed by foreign-born attackers is a manageable hazard. The threat of terrorist entry through the southwest border is minuscule even when compared to the overall manageable hazard posed by foreign-born terrorism.

Illegal Immigrants, Asylum Seekers, and Foreign-Born Terrorism on U.S. Soil

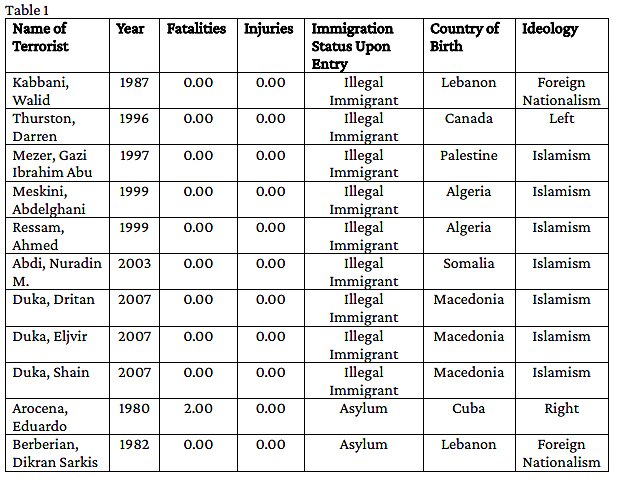

In my research, I have identified 219 foreign-born terrorists who committed attacks on U.S. soil, intended to commit attacks on U.S. soil, threatened attacks here, or tried to fund domestic terrorism.2 Those 219 foreign-born terrorists were responsible for 3,046 murders and 17,077 injuries in attacks on U.S. soil from 1975 through the end of 2022.3 The annual chance of being murdered in a terrorist attack committed by a foreign-born terrorist from 1975–2022 is about 1 in 4.3 million per year.4 The annual chance of being injured in such an attack is about 1 in 774,000 per year. By comparison, the annual chance of being murdered in a criminal non-terrorist homicide in the United States was about 1 in 20,134 during the 1975–2022 period. The chance of being murdered in a normal homicide is about 316 times greater than being killed in an attack committed by a foreign-born terrorist.5 During that time, 97.8 percent (2,979) of all those murdered in terrorist attacks were murdered on 9/11, and 86.9 percent (14,842) percent of all people injured in foreign-born terrorist attacks were injured on 9/11.

During that time, the number of people murdered in attacks on U.S. soil committed by a foreign-born terrorist who entered illegally was zero. The number of people injured in an attack committed by a foreign-born terrorist who entered illegally was zero. Suffice to say, the number of people killed or injured by an illegal immigrant who entered illegally across the U.S.-Mexico border is also zero.

However, nine foreign-born terrorists entered the United States illegally during the 1975–2022 period. Three of the nine convicted illegal immigrant terrorists entered illegally by crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. They are Dritan Duka, Eljvir Duka, and Shain Duka, and they entered illegally in 1984 when they were aged 5, 3, and 1, respectively. They were arrested almost 23 years later, in 2007, while plotting to attack Fort Dix, New Jersey. Of the other illegal immigrant terrorists, five illegally crossed the U.S.-Canada border (Kabbani, Thurston, Mezer, Ressam, and Abdi) and one was a stowaway on a ship (Meskini).

The Duka brothers were “got aways,” which is defined as an unlawful border crosser who (1) is directly or indirectly observed making an unlawful entry into the United States; (2) is not apprehended; and (3) is not a turn back.6 There have been many got aways in recent years, likely over 1.2 million in total.7 There is little evidence that a larger population of illegal immigrants in the United States, a population augmented by more got aways, poses an increased risk of terrorism. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) should be vigilant to the possibility, and the situation could always change, but there is little reason to worry more than usual.

Thirteen terrorists were allowed to enter as asylum applicants, and they are responsible for 9 murders and about 669 injuries in attacks on U.S. soil during the 1975–2022 period. The annual chance of being murdered by a foreign-born terrorist who entered as an asylum applicant or who was granted asylum shortly after entering is about 1 in 1.5 billion per year. The annual chance of being injured in an attack committed by a foreign-born terrorist who was present as an asylum seeker is about 1 in 20 million per year. None of the asylum seekers who became terrorists entered by crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Only one was from the Western Hemisphere; Eduardo Arocena from Cuba, and he committed his last attack in 1980.8