Dear Chair Waters, Ranking Member McHenry, and Members of the Committee,

My name is Nicholas Anthony. I am a policy analyst at the Cato Institute’s Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives. I appreciate the opportunity to provide input to assist the committee with its hearing titled, “Oversight of the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network.”1 The Cato Institute is a public policy research organization dedicated to the principles of individual liberty, limited government, free markets, and peace, and the Center for Monetary and Financial Alternatives focuses on identifying, studying, and promoting alternatives to centralized, bureaucratic, and discretionary monetary and financial regulatory systems. The opinions I express here are my own.

Measuring Effectiveness and Accountability

The Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) is charged with combatting financial crimes like money laundering and terrorist financing. In practice, that has resulted in FinCEN becoming a depository of financial information on Americans both large and small. FinCEN reported that it received more than 20 million Bank Secrecy Act (BSA) reports in 2019 alone.2 And it is estimated that complying with the BSA in 2019 cost the U.S. financial industry $26.4 billion––up from an estimated $4.8 billion to $8 billion in 2016.3 However, what is not known is what was done with those 20 million reports. FinCEN referred to the reports as providing “potentially useful information to agencies whose mission is to detect and prevent [financial crimes],” but it did not say if those reports were in fact useful to that mission.4

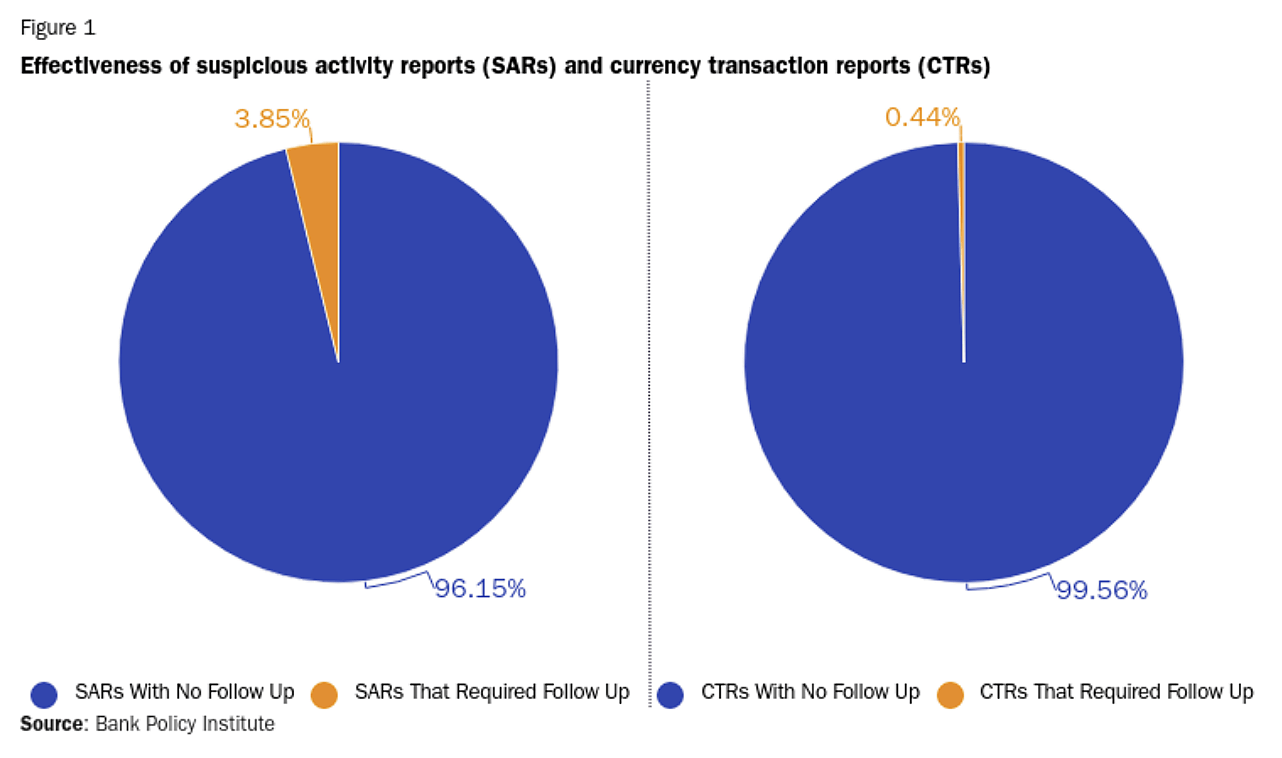

A 2018 study from the Bank Policy Institute (BPI) provides strong evidence that those reports were not useful.5 After surveying a sample of 19 financial institutions, BPI found that a median of 4% of suspicious activity reports (SARs) and an average of 0.44% of currency transaction reports (CTRs) required additional review from law enforcement (Figure 1). Even fewer reports likely resulted in stopping or apprehending criminals.

It’s time for FinCEN to begin reporting on its own activity.6 FinCEN should annually report, at the least, how many SARs and CTRs:

- Required a desk rejection

- Required secondary review

- Led to law enforcement action

- Led to a unique criminal conviction

- Led to a criminal conviction in conjunction with an existing investigation

While more information would be preferable, these surface-level statistics could greatly improve how Congress and the public evaluate the effectiveness of FinCEN and the anti-money laundering (AML) regime at large. Americans deserve to know how the government justifies enforcing this regulatory framework, but their elected representatives cannot properly judge the effectiveness of FinCEN without more information.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.