Chairman Wyden, Ranking Member Crapo, and Members of the Committee: Thank you for inviting me to testify today.1

I always welcome testifying before Congress on issues of importance to me and the nation, but I must admit that my presence here today is bittersweet. U.S. preference programs, in particular the Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) and African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), have long been so uncontroversial and universally accepted in Congress that committee hearings like today’s were unnecessary. In 2018, for example, GSP renewal passed the House by lopsided vote of 400–2, and full committee hearings have long been unnecessary.2 That the program has now sat expired for more than three years, and that we’re here today as trade-watchers openly contemplate AGOA’s expiration too, is an unfortunate testament to the state of U.S. trade policy in 2024.

As I and my Cato Institute colleagues have long documented, U.S. trade preference programs are far from perfect.3 Product exclusions, import limits, eligibility criteria, and complex administrative and customs requirements all limit the programs’ usefulness for foreign exporters, American importers and consumers, and U.S. foreign policy. But the perfect should not be the enemy of the good, especially—as the last few years have unfortunately re-taught us—when the alternative is nothing at all. And, as I’ll explain, there are strong economic, geopolitical, and moral reasons to continue—if not expand—these programs, especially today.

The Economic Case

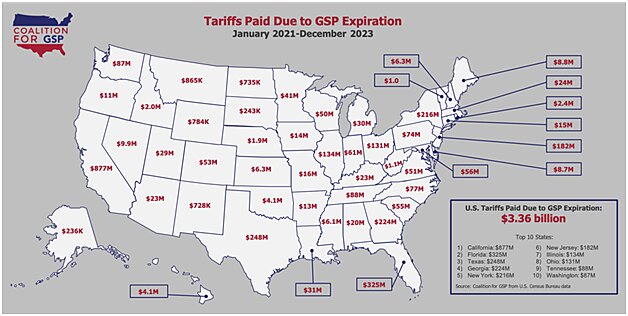

Preference programs have delivered important economic benefits for the people—here and in developing countries—participating in them. The recent expiration of GSP provides an unfortunate example: according to the Coalition for GSP, for example, American companies between 2021 and 2023 paid almost $3.4 billion in additional tariffs because the program was expired.4

Meanwhile, UNCTAD estimates that AGOA saves U.S. importers approximately $250–300 million per year in foregone tariffs (or $5–6 billion between 2001 and 2021)5—savings that these companies can use to expand their operations or simply pass on to their American customers.

A few billion dollars in tariff savings arguably means little to a $27 trillion U.S. economy that imported more than $3.8 trillion in goods and services last year alone, but it is critical to the people here and abroad whose livelihoods depend on these programs. Indeed, GSP beneficiaries in the United States are predominantly small businesses: According to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, for example, “The typical beneficiary [U.S.] company employs about 20 people, and GSP saves them between $100,000 and $200,000 in duties.”6 Supposedly “small” tariff savings for them can mean the difference between eking out a small profit and declaring bankruptcy—especially given that, as has been widely reported, many small businesses have been forced to take out high-interest loans or lines of credit to cover new tariff costs.

Consider the following examples:

- A 20-person business in California selling travel goods explained in 2021 that it was facing the risk of closure because GSP expiration forced the company to change suppliers multiple times and pay more than $800,000 in tariffs.7

- A Michigan company that sells Cambodian school supplies to local K–12 schools was forced to reduce its staff by almost half after GSP expired. According to the owner, the episode “nearly put us out of business.”

- A 55-person, employee-owned company in Wisconsin that imports food products from GSP beneficiary companies paid more than $20,000 in extra tariffs and has suffered lower sales because it was forced to pass on some of these costs to its American customers.8

- Also in California, a jewelry company owner has accumulated over $3 million in debt to pay for $4.5 million in extra tariffs since GSP has been expired.9 He’s slashed his company’s staff from 20 employees to just 5 and has finally stopped waiting for Congress to renew GSP, instead preparing to close the business completely.

- A Boise, Idaho curry company run by a husband and wife duo for 15 years now faces closure because they’ve paid more than $150,000 in additional tariffs and, unable to absorb these costs, have been removed from the shelves of their two biggest buyers, Whole Foods and Sprouts.

Larger American businesses have been affected too, but I highlight the smaller companies because the large ones have the resources to not only absorb or pass on higher tariff costs but also to adjust to their global supply chains—including, as we’ll discuss in a moment, by moving to Chinese suppliers. Often, the little guys have no such options.

People in developing countries have, of course, benefit from these programs too—and, being some of the poorest people on the planet, they disproportionately suffer when the benefits stop. Under AGOA, for example—

- Qualifying apparel exports from Kenya increased from $55 million to $603 million between 2001 and 2022, constituting almost 68 percent of Kenya’s total exports to the United States.10

- In Lesotho, eligible apparel exports accounted for 89 percent of country’s total exports from 2001 to 2020, around $6.2 billion during the period.11

- AGOA has proven essential for jumpstarting Namibia’s nascent and growing beef industry, which in 2019 “became the first country in Africa to export beef to the United States after 15 years of working to satisfy safety regulations and logistics.”12

- Automotive goods from South Africa increased by 447.3 percent between 2001 and 2022.13

- AGOA has also helped chocolate and basket-weaving materials from Mauritius; buckwheat, travel goods, and musical instruments from Mali; sugar, nuts, and tobacco from Mozambique; and wheat, legume, and fruit juices from Togo.14

This increased trade has produced tangible economic benefits for people in Africa. For example, the Brookings Institution estimates that AGOA-covered apparel exports alone have “led to the creation of tens of thousands of jobs” in Lesotho, Ethiopia, Mauritius, Madagascar, and Kenya.15

On the other hand, losing AGOA preferences can severely harm African nations—and their neighbors. Ethiopia’s 2022 suspension from the program, for example, threatens the nation’s textile- and apparel-focused industrial parks, which employ around 90,000 women aged 18–25 and have thrived because of duty-free and quota-free access to the U.S. market and hundreds of millions in foreign investment since 2014.16 Meanwhile, Madagascar’s recent removal from AGOA punished not only that country but “the five regional partners from whom they sourced their apparel inputs.”17

Aggregate data reiterate the importance of U.S. preference programs for developing countries. While GSP imports were a tiny share of all U.S. imports in 2021, they were almost 9 percent ($21.1 billion out of $235 billion) of all imports from GSP beneficiary countries that same year.18 The skew is even greater for AGOA imports: last year they were only 0.30 percent of all U.S. imports but accounted for a whopping 32.3 percent of eligible countries’ exports to the United States.19

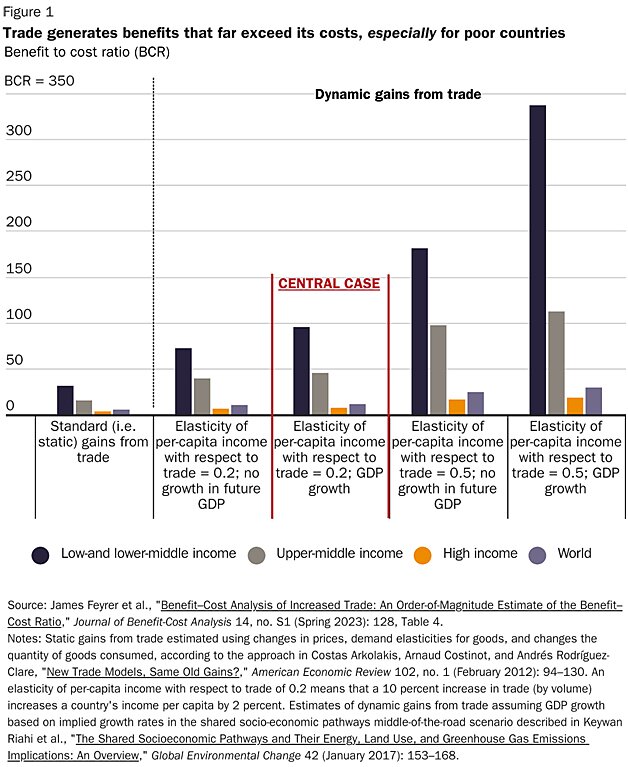

More broadly, a study in the Spring 2023 special issue of the Journal of Benefit-Cost Analysis finds that a liberalization-driven 5 percent increase in global trade, accounting for both benefits and costs to import-competing industries, would generate benefits “only” 7 times greater than costs for rich countries like the United States but an astounding 95 times greater ($1.4 trillion in benefits at a cost of $15 billion) for low- and lower-middle income countries, such as those benefiting from U.S. preference programs. The authors thus conclude that freer trade is “one of the top interventions” for global development: it “is modestly good for rich countries, very good for upper–middle-income countries, and amazingly good for the poorer half of the world.”20

Of course, the effects of U.S. preference programs are orders of magnitude smaller than the ones modeled here, but the data above nevertheless demonstrate the disproportionate benefits that GSP, AGOA, and other market-opening initiatives provide to people living in world’s poorest countries.

This also demonstrates why, as my colleague Johan Norberg documents in a new Cato Institute essay, U.S. trade with developing countries has not facilitated a “race to the bottom” for labor and environmental conditions in those places but in fact much the opposite. In particular, he offers reams of data showing that global capitalism—and the economic growth, rising living standards, and technological proliferation it foments—has benefited both the developed and developing world alike.

- On labor, for example, the International Labour Organization finds that countries more integrated the global economy had much larger declines in elementary and lesser-skilled jobs (a proxy for low incomes and bad working conditions) between 1994 to 2019.21 The share of workers living in extreme poverty has collapsed, with the biggest drops again occurring in more globalized Asia (and not just in China) than less-connected Africa. As the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) concluded a few years ago: “the worst of fears about a race to the bottom do not appear to have materialised systematically in the real world, though examples do arise. A large empirical literature seems to point, if anything, to the opposite conclusion.”22

- The story on the environment is more complicated, but eventually just as optimistic. Research shows that countries’ early-stage urbanization and industrialization tends to worsen pollution levels and other environmental conditions, but that this trend reverses (i.e., environmental conditions improve) as national wealth increases, industry advances, and citizens demand tighter regulation. As the Financial Times documented last year, the same “environmental Kuznets curve” applies to CO2 emissions23, which appear to be declining today even in China.24 Just as promising is the fact that less-developed nations are greening more quickly than their more-developed peers did, and trade again plays a big role in the process by helping to make poorer countries richer and by spreading technology developed by advanced countries. Thus, for example, economists Jeffrey Frankel and Andrew Rose have found that increased trade “correlates with reduced air pollution, independent of the effect wealth had on environmental progress.”25

Real-world cases disproving the race-to-the-bottom also abound. Bangladesh, for example, has long been one of the poorest places on the planet but has experienced several decades of expanded trade (especially in textiles and apparel), strong economic growth, and dramatic declines in poverty.26 In Cambodia, meanwhile, a manufacturer that once benefited from GSP reported paying between two to five times the Cambodian minimum wage, plus benefits.27 A maker of AGOA-covered skincare products in Togo “pay[s] four times the current wage in Togo” and is “seen as a model for advancing gender equality.”28 Another AGOA participant, an Ethiopian footwear company, offers salaries three times the industry average, along with health insurance, transportation, and investments in the education of workers’ children.29 These firms are certainly not alone.30

Of course, not all beneficiary companies are good actors, and more work needs to be done in poorer countries. But keeping them poor—including by blocking off trade or attaching even more conditions to U.S. preference program benefits—will delay (if not thwart) the real progress they’re making.

Finally, it is important to note that new tariffs imposed since GSP expired do not seem to have encouraged U.S. importers to Buy American instead of from GSP-eligible countries. For starters, GSP import levels are roughly at or above pre-expiration levels (depending on your data source).3132 For these imports, Americans are just eating the tariffs. As we’ll discuss next, moreover, there is mounting evidence that U.S. importers and multinational manufacturers have shifted from GSP countries to other foreign suppliers, most notably China. Thus, GSP expiration did not mean more American manufacturing; it just meant more Americans paying more taxes—an unsurprising result, given that the programs are designed to minimize competition with American producers and workers.

The Geopolitical Case

Even if the economics were not so ironclad, U.S. trade preference programs would probably be worth maintaining for their geopolitical effects alone.

First, beneficiary countries often provide a strategic alternative to imports from China. Beyond the AGOA apparel examples above (China represented about 24 percent of all U.S. textile and apparel imports last year33), GSP expiration provides an instructive, albeit frustrating, lesson in this regard. According to multiple businesses interviewed by the Coalition for GSP and the Wall Street Journal, tariff savings under the program allowed them to shift suppliers from China to non-China sources. However, when GSP expired, the Journal noted “119 developing countries and territories, including Thailand, Brazil, the Philippines, Indonesia and Cambodia, that had been eligible for duty-free import to the U.S. were hit with tariffs.”34 As a result, it has become more financially sensible for many companies to shift their sourcing back to China35—even though many of the Chinese products at issue are subject to U.S. tariffs, too. (Overall, 95 percent of the tariffs paid because of GSP expiration are for products that also subject to Section 301 tariffs.36)

Travel goods are the Journal’s indicative example: U.S. imports of bags, wallets, and related items from China declined by about 64 percent from January 2018 to December 2020 but then increased by 48 percent after GSP expired.37 Without GSP, the paper explains, “U.S. importers had to choose between hiking prices for consumers, absorbing the hit through lower profit or finding a cheaper place to manufacture.” That “cheaper place,” it turns out, was the very Chinese mainland that they recently left, thus “denting investment in countries that show promise as alternatives for manufacturing outside China’s vast factory floor.” Indeed, some of the largest GSP beneficiary countries—Indonesia, Cambodia, Thailand, Brazil, and the Philippines—are locations the U.S. government has tried to promote as China manufacturing alternatives.

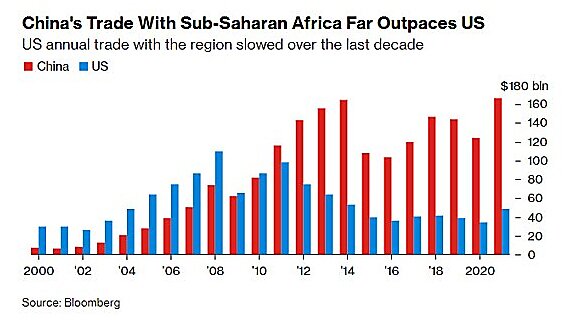

For this very reason, the House China Select Committee included GSP reauthorization among its 150 policy recommendations to “to fundamentally reset the United States’ economic and technological competition with the People’s Republic of China.” In particular, the Commission noted that reauthorization would “promote economic development in the roughly 120 developing countries covered by GSP,” and recommended that Congress update the program to, among other things, “accelerate supply chain shifts out of the PRC market” and “provide certainty for industry as they contemplate supply chain investment decisions outside of the PRC.”38 Second, U.S. preference programs are a cost-effective way to boost relations with key developing country allies around the world—nations that, whether due to investment ties, diplomacy, or economic gravity—have been increasingly pulled into China’s geopolitical orbit. As I wrote last year, leaders in Latin America, Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East have recently expanded economic ties with Beijing, while clamoring for—and often not receiving—similar levels of engagement from the United States.39 Just last week, for example, former GSP beneficiary Cambodia renamed a major road in its capital “Xi Jinping Boulevard,” which the nation’s Prime Minister attributed to the nations’ “inseparable” relationship.40 In Sub-Saharan Africa, Bloomberg reports that annual trade since 2008 has declined substantially with the United States but done just the opposite with China41:

Between 2016 and 2020, moreover, Chinese investment in the region was far above that of all other countries and almost three times that of the third-place United States:

As I and others42 noted at that time, the economic data do not mean that the governments of these African nations—or of Brazil and other developing countries—have suddenly joined “Team China” and abandoned the United States. Howver, three important points remain true. First, these countries greatly value American investment and access to the U.S. market. Second, the United States government is not giving them either—especially as compared to the country that’s supposedly America’s top economic and geopolitical rival. Third, that foreign aid is an inadequate substitute for real bilateral economic engagement. On this last point, UNCTAD reports (emphasis mine): “During 2001–2021, total United States goods imports from the AGOA countries reached $791 billion… about five times larger than aid, with the total value of United States foreign economic assistance obligations to sub-Saharan African countries during fiscal years 2001 through 2019 being $145 billion.…”43

The United States still has many things going for it in any so-called “Great Power Competition” with China—including many non-economic factors and foreign countries’ strategic self-interest in playing both sides of the rivalry. Nevertheless, one of America’s longstanding geopolitical advantages has been our economic openness and engagement abroad, and, at a time when federal budgets are tight, China’s overseas influence is growing, and public distrust of foreign aid and overseas interventionism is rising, preference programs are a smart and easy way to boost global stability and U.S. foreign relations without spending a penny of taxpayer money.

The Moral Case

Finally, there is a strong moral case for unilaterally reducing barriers to trade with developing countries. In 2022, the median annual income of people in GSP-eligible and AGOA-eligible countries was a mere $6,507 and $4,017, respectively (adjusting for purchasing power). That same year, it was more than $76,000 in the United States.44 Program beneficiary countries are home to some of the poorest people on the planet, many of whom depend on duty-free access to the U.S. market, no matter how limited it may be. In the tiny Solomon Islands (724,000 people and PPP-adjusted GDP per capita of $2,66545), for example, GSP-eligible exports of around 400–500 tons of canned tuna per year constituted about 18 percent of the nation’s GDP and about 1 in every 30 formal-sector, wage-earning jobs.46 Since GSP expired, however, those same exports now face tariffs of 12.5 to 35 percent, and have essentially ceased, replaced by imports from larger countries in Southeast Asia and Latin America.

More broadly, a 2018 paper from Emanuel Ornelas and Marcos Ritel finds that least-developed countries (LDCs), defined by the United Nations as gross national income (GNI) per capita of less than around $1100 per year, see a significant increase in their exports as a result of trade preference programs in the United States and elsewhere.47 Thus, these “very poor” countries are the programs’ chief beneficiaries.

Conclusion

One of the best and easiest ways to help the world’s poorest people live better lives is to help them get rich, and trade is a key part of that enrichment. U.S. preference programs are far from perfect, nor are they alone a sufficient level of American economic engagement with the developing world. Nevertheless, they provide undeniable economic and geopolitical benefits, while helping to fight global poverty make the world a better, greener place. Maintaining them is the least we can do.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.