Let me first commend the Chairman, and the Committee staff, for their efforts in crafting the "Protecting American Taxpayers and Homeowners (PATH) Act." Rarely does Congress so directly, clearly and accurately identify a problem and craft a solution actually addressing the problem.

Need for Reform

It should be beyond dispute that our nation's system of residential mortgage finance is badly broken. A few tweaks here and there will not suffice. Major structural reform is needed. Never again should the taxpayer be forced to pay tens of billions to bail-out the mortgage finance industry. It is well worth remembering that the most recent bailout is not the first. The Savings and Loan crisis of the 1980s was essentially a taxpayer financed bailout of the mortgage-finance and housing sectors. We cannot leave the taxpayer holding the bag the next time the housing market goes boom and bust, which it will. We have not ended either the business cycle or the related housing cycle. If anything, our current system has made those booms and busts worse.

Let us also make no mistake. The recent recession, from which we are still recovering, was a direct result of the boom and bust in our housing market. This boom and bust was caused by, among other policy mistakes, our current system of mortgage finance. Eight and half million workers lost their jobs in the recent recovery. We are still 2.5 million jobs below the peak, and that excludes population growth. Housing starts fell around 1.7 million units on an annual basis. I could go on, but we are all aware of how painful the recent recession has been. Perhaps the most painful part was that the recession was avoidable. Had we a different system of mortgage finance, we could have avoided much of the pain of the recent years. If we choose to retain the current system or make only cosmetic changes, we guarantee a repeat of the recent recession. I believe such would be the height of irresponsibility.

This summer sadly marks the tenth anniversary of the discovery of Freddie Mac's accounting scandal, which led to the recognition of widespread regulatory failings at Freddie, Fannie and at their previous regulator OFHEO. Unfortunately, efforts to reform the regulatory structure of Fannie and Freddie failed until 2008, which by then was too little, too late. Even what was passed in the Housing and Economic Recovery Act of 2008 (HERA) has been, in part, ignored. HERA established a receivership mechanism that, if used, could have protected the taxpayer from loss. As we all know, it was not used.

While the eventual failure of Fannie and Freddie seemed a foregone conclusion to me by 2004, perhaps others can be forgiven for believing we had defeated the business cycle and that housing prices would soar forever. It is hard to either understand or forgive such a position today. Those who argue for the status quo, or only cosmetic changes to it, would take us back down the painful path of financial crisis and recession.

We should also remember Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were two of the largest corporate financial restatements in history. These were not innocent companies sunk by a hundred year storm. Both companies were deeply corrupt—a depth of corruption that can only result from their protected, entrenched status. Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers, and Countrywide are all gone. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac merit the same fate. In so many ways, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have been and continue to be emblematic of what is broken in both Washington and corporate America. If we cannot end entities so obviously broken as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, then we have almost no hope in addressing other pressing issues that face our country.

There's no "need" for a guarantee

Objections to the elimination of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac often assert that such would be "dangerous" because our mortgage market needs a government guarantee to function. Such an assertion is false on a variety of fronts. First, our mortgage market is characterized by several government backstops besides Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The Federal Reserve has purchased trillions of dollars in mortgage-backed securities. The Fed's 13-3 powers were also used to support asset-backed commercial paper funding non-mortgage debt during the crisis. In addition, we have the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), Government National Mortgage Association (GNMA), and the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs). One could argue that deposit insurance for banks and thrifts also serves as a backstop for the mortgage market. While I would eliminate or roll back most of these interventions, that does not change the fact they are indeed there. Even in the absence of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, our mortgage market maintains considerable governmental support.

Further proof of the mortgage market's ability to function without Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac is the existence of the jumbo mortgage market. Thirty-year fixed-rate financing is readily available at affordable rates in the United States without the backing of a government sponsored enterprise. A handful of lenders today offer jumbo rates that do not differ from conventional mortgage rates. If a government guarantee was essential, we would expect the jumbo market to be relatively small compared to the relevant portion of the housing market. It is not. Homes valued above the current FHA high-cost limit are about 4 percent of the overall housing market, whereas the jumbo market is currently around 5 percent of the mortgage market. Homeowners in the jumbo market are actually more likely to have a mortgage than those whose homes fall under the conforming limit. Families with incomes placing them in the likely category of jumbo borrower are also more likely to be homeowners than other families. The notion that without Fannie Mae and Freddie Mae we would be a nation of renters is simply pure fiction.

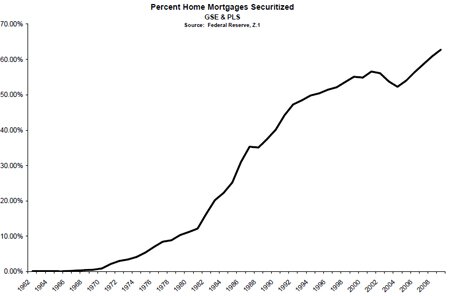

Homeownership rates, with the exception of the recent boom, had stabilized in the low 60 percents in the beginning of the 1960s. By 1969, the national homeownership rate reached 64.3 percent. At this time, the percent of mortgages securitized was in the low single-digits and the secondary market was irrelevant. Over 70 percent of mortgages were held on the balance sheets of depositories, with the remainder largely held by insurance companies. From 1982 to 1992, securitized mortgages increased from around 10 percent to just over 50 percent of the mortgage market. This, however, was a time of stagnating—even declining—homeownership. Even during the temporary boom in homeownership, from 1995 to 2004, the percentage increase of mortgages securitized was relatively modest. It is impossible to objectively examine the last 50 years of data and conclude that the creation of the U.S. secondary mortgage market has any noticeable long-run impact on homeownership rates.

Nor does the data support the notion that the growth of Fannie and Freddie actually lowered mortgage rates relative to Treasuries. In the decade before the growth in securitization, between 1971 and 1981, the spread of the 30 year fixed over the 10 year Treasury was 1.56. From 1982 until the financial crisis in 2008, that spread averaged 1.72.

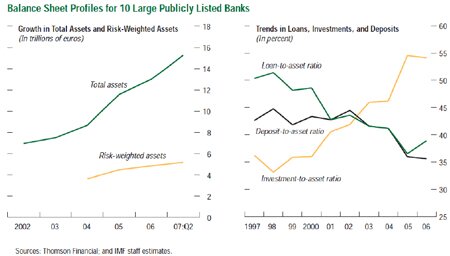

One thing that the growth of Fannie, Freddie, and the secondary mortgage market has achieved is a massive increase in the leverage of our mortgage finance system. As illustrated below (from IMF), the growth of securitization , along with development of the Basel capital standards has greatly reduced the amount of corporate equity standing behind our mortgage market.

The combination of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Basel capital accords resulted in a mortgage market that in 2006 was leveraged almost 60 to 1 on the part of financial institutions. Even a mortgage market consisting solely of prime, high-quality mortgages would have resulted in losses given that excessive leverage. Had all mortgages been held as whole loans on the balance sheets of depositories, the system would have included an additional $214 billion in capital in 2006.

An important lesson gleaned from the financial crisis is that risk will flow to the leastcapitalized segment of the market. The fact that Bear Stearns was leveraged over 30 to 1 has received considerable notice by both academic and journalist commentators. Sadly, that the Fannie and Freddie guarantee business was leveraged over 200 to 1 receives far too little attention. This was a system destined to fail, and fail it did.

Another rationale given for the continued existence of Fannie and Freddie is the 30 year fixed-rate mortgage. Let me be very clear: the 30-year mortgage exists in the jumbo market. It would exist without Fannie or Freddie. Borrowers choose mortgages based upon their relative costs. In much of Europe, adjustable-rate mortgages are priced more attractively than fixed rate mortgages. This is due, in considerable part, to the worse record of European central banks on the issue of inflation. For instance, in Italy from 1969 until the adoption of the Euro, inflation averaged nine percent per year with wide fluctuations year to year. With such an erratic macroeconomic environment, lenders will only offer fixed-rate financing at considerable cost. As bad a record as the Federal Reserve has, by the standards of Europe, it has done relatively well. The future of the 30-year mortgage in the United States depends less on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and more on the behavior of the Federal Reserve.

One should also recognize that long-term fixed financing is readily available for the auto loan market. Seven year auto loans are readily available at affordable rates without the support of a government sponsored enterprise. They are even available at loan-to-value ratios that mirror those found in the mortgage market. The notion that such financing would not be made available in the mortgage market absent a government sponsored enterprise is, again, a pure fiction.

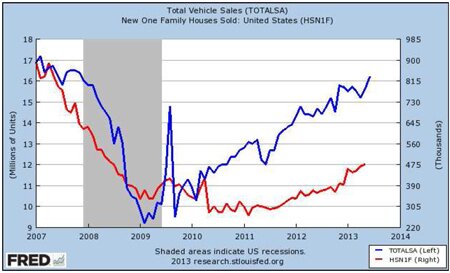

It is also worth noting that the auto market, without a government sponsored enterprise, recovered more quickly than the housing market. As the chart below illustrates, vehicle sales followed a similar path to that of home sales. Not surprising, since the decision to purchase a car is made with similar concerns as that of purchasing a home. But where the auto market began recovering in 2009 and 2010, the housing market continued to limp along. While any comparison is imperfect, the performance of the auto market suggests that a government guarantee is not needed, even during a recession.

On other occasions, the Committee has heard how other countries manage to provide long-term fixed-rate affordable mortgage financing without government sponsored enterprises and do so with homeownership rates often above that of the United States. As those facts are clear, I will not repeat them here, only to note many other countries have far better functioning mortgage markets with similar or better results than the U.S. without such an extensive cost to the taxpayer and to the economy.

Of course, that might be the most important point to remember. Despite all the massive subsidies and distortions, the truth is we have very little to show for it. We know one must break some eggs to make an omelet, but at some point it becomes to reasonable to ask "Where's the omelet?" Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have delivered almost nothing in terms of increasing the long-run homeownership rate. They haven't even narrowed the homeownership gap between white and African-American households. At the height of the bubble in 2007, homeownership rate for whites was 76.5 percent, while that for African-Americans was 54 percent, leaving a gap of 22.5 percent. In 1910, before the creation of FHA, Fannie Mae, or Freddie Mac, that gap was 23.5 percent. In more than one hundred years, the difference in white and African-American homeownership rates has decline a whole 1 percent. I must note that the gap had narrowed to 18.8 percent by 1980—before the massive growth of our agency-driven secondary mortgage market. The simple fact is that the growth in Fannie Mae's and Freddie Mac's market share has been associated with a growing (worsening) gap between the homeownership rates of whites and African-Americans. Only if the purpose of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was to worsen existing economic inequalities could you even try to call these companies "successes".

Nor has the homeownership gap improved by income. In 1994, the gap in homeownership rates for families with incomes above the median, compared to families below, was 30.4 percentage points. In the first quarter of 2013, that gap is 30.0 percentage points. That gap actually worsens during the boom to a high of 32.3 in the first quarter of 2004. Again, our current mortgage-finance policies have, if anything, increased economic inequality in America, not reduced it. Fannie and Freddie have managed to be both inefficient and unjust.

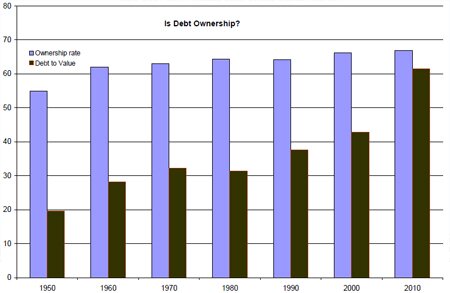

Ultimately what our current mortgage finance polices have wrought is a massive increase in household debt with little to show for it. As the following graph illustrates, the homeownership rate has stagnated since 1960, yet the average mortgage debt to home value has dramatically increased. In 1960, our housing market was one of equity, rather than debt. In fact, before 1960, a majority of owners owned their homes free and clear with no mortgage at all. Today, owners have less than 30 percent equity, on average.

Rather than producing a nation of homeowners saving wealth to pass along to their children, we have created a nation of families drowning in debt. While most families dream of becoming homeowners, I suspect few dream of becoming highly leveraged. The primary result has simply been to push up home prices beyond the reach of many families.

Ending Too-Big-To-Fail

As the Committee is well aware, the problem of too-big-to-fail financial institutions continues to distort our capital markets. Fannie and Freddie are the poster-children for TBTF. Freddie is close in size to both Citibank and JP Morgan. If we are not willing to resolve Freddie, which is far less complex than either Citibank or JP Morgan, then I believe market participants will continue to view our largest banks as TBTF. In order add credibility to efforts to end TBTF, the place to start is Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

PATH Act

Given the urgent need to eliminate Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, I want to commend the Chairman for putting forth legislation that does so. First a few general comments. Even if the PATH Act were enacted, our mortgage market would still be characterized by considerable and excessive government intervention. A freer mortgage market, yes. A free mortgage market, no. As someone who has closely studied our housing and mortgage markets for almost two decades, I believe that the long-run impact on homeownership and mortgage rates would be insignificant. That said, there is considerable potential to protect the taxpayer and increase financial stability.

First, the elimination of Fannie and Freddie is essential. Given the ability to "run" the companies while in receivership, I would suggest to the Committee that an additional five years of conservatorship is unnecessary. A two-year lead would give FHFA more than sufficient time to prepare for a receivership.

The reduction in GSE/FHA loan limits should also be accelerated. According to the Census Bureau's American Community Survey, the U.S. median home value (2011) was $173,600. The Census Bureau reports that only about 25 percent of homes are valued more than $300,000. To be blunt, the loan limit reductions in PATH are modest, at best, and would continue to leave the vast majority of the housing market at the backing of the government. A loan limit of $525,500, as ultimately envisioned by the PATH Act, still covers around 90 percent of the U.S. housing market. A more reasonable number would be closer to $200,000.

I especially want to commend the Chair's inclusion of reforms to stop attempted abuses of eminent domain. While I would like to see such provisions extended beyond the mortgage space and protect all homeowners, the included prohibitions are an important step. According to the Census Bureau's American Housing Survey, between 30,000 and 40,000 families are displaced from their homes every year due to some governmental action. Around a quarter of these families live below the poverty level, and about half are African-American families. When the government takes someone's home, it is disproportionately the home of someone lacking the political power to fight back. I would urge the Committee to consider the issue of eminent domain more broadly in its future deliberations.

FHA Reform

Fannie and Freddie may be the weakest links in our mortgage finance system, but they are not the only weak links. The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) poses a considerable risk to the taxpayer. Eliminating Fannie and Freddie without FHA reform runs the very real risk that shoddy lending flows from the GSEs into FHA. We already witnessed a migration of subprime from GSEs and private label into FHA after the onset of the financial crisis. Additional FHA reforms are essential. Over two years ago (May 25, 2011), I made a number of suggestions to the Subcommittee on Insurance, Housing & Community Opportunity regarding FHA reform. I refer the Committee to that testimony for my views on FHA reform. I would add only two comments to that testimony. First, it is encouraging to see a few of my suggestions on FHA reform surface in the Chairman's bill. Second, there are a handful of issues on FHA where I believe the Chairman's draft should go further. Foremost among these is the need for greater down-payments in FHA. Under PATH, first-time buyers will still be able to get an FHA loan with only 3.5 percent down. I recognize a number of other needed reforms have been included in the bill, but I would urge the Committee to consider increasing FHA's down-payment requirements beyond those already in the bill. Again, I want to commend the many needed and important changes to FHA contained in the PATH Act.

One must also recognize that our mortgage finance system is a "house of cards"—the GSEs were the largest distortion in this market but certainly not the only one. While the Basel capital changes and other reforms in Title IV are helpful, I believe we would achieve greater financial stability by abandoning the Basel process altogether and adopting flat, but high, capital standards for banks.

Conclusions

I thank the Committee for inviting me to offer my thoughts on mortgage finance reform. As the Committee will note from my biography, I have spent most of the last two decades involved in various aspects of housing and mortgage finance policy. Without a doubt, I believe housing is a critical component of our economy. Moreover, I believe that housing is one of thebasic necessities of life, if not the most important. Without stable, decent, and affordablehousing, many other goals in life become quite difficult, if not impossible, to achieve.

With that in mind, our current system of mortgage finance has not helped facilitate the dream of affordable, accessible homeownership. Our current system has largely encouraged families to become highly leveraged, leaving both themselves and our overall economy at greater risk. Our current system has not resulted in longer term gains in homeownership. It is far past time we recognize the failures of our current system and move toward a better system that effectively serves homeowners and taxpayers.

Examples of stable reliable long term funding can be found in many contexts, including our jumbo mortgage market. Long-term affordable financing is also found in our auto market, as well as in the mortgage market of other developed countries. This funding is and can be provided without a government backstop. The subsidies provided via Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac were largely captured by the companies themselves and various service providers in the real estate and mortgage industries. I have zero doubt that the existence of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac has made us considerably poorer as a country. We would have been better off if they had never existed. While it is unfortunate that Washington lacked the foresight to correct that error in the past, we now have the opportunity to chart a path forward that is more efficient, effective and just.