Chairman Wyden, Ranking Member Crapo, and members of the committee, thank you for inviting me to testify at today’s hearing, “House Republican Supplemental IRS Funding Cuts.”

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) included $79 billion of added funding for the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), which will help to double the agency’s budget in nominal dollars between 2023 and 2031.1 House Republicans would rescind most of the new funding in the recent Limit, Save, Grow Act.

The IRS has been the focus of attention because of its poor taxpayer services and outdated technologies. The agency recently issued a Strategic Operating Plan (SOP) that promised major improvements.2

Unbalanced Funding Increase

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) included $79 billion in mandatory spending for the IRS over the coming decade, with $45.6 billion for enforcement, $25.3 billion for operations support, $4.8 billion for business systems modernization (technology), and $3.2 billion for taxpayer services.

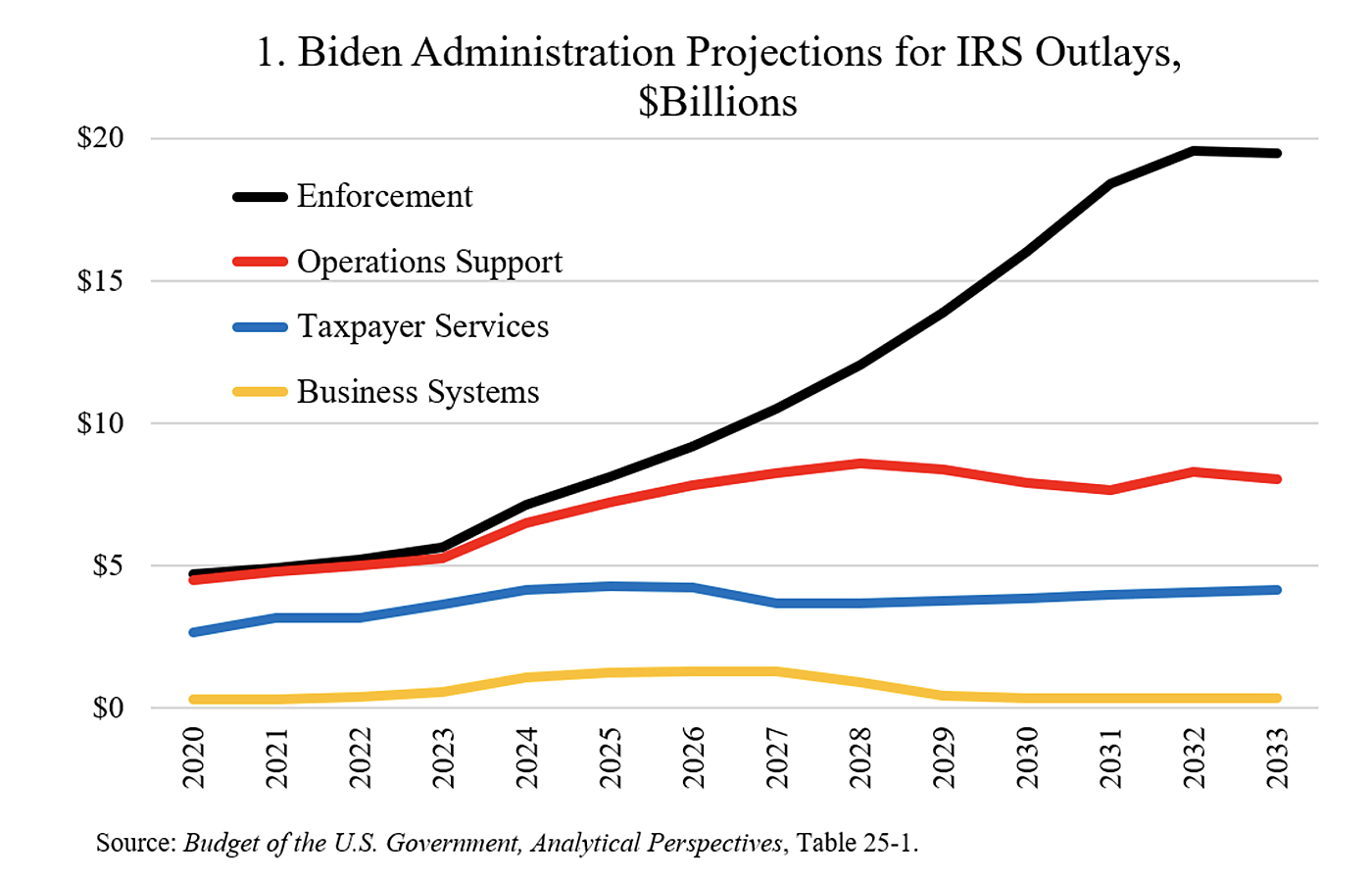

Figure 1 shows the Biden administration’s proposed spending increases for the four main budget components of the IRS.3 The figures include the IRA funding plus projected discretionary funding.

Outlays for taxpayer services and business systems are projected to rise for a few years and then fall, while enforcement outlays will grow rapidly and more than triple by 2031. Enforcement spending will rise from 38 percent of the total this year to 61 percent by 2033.

These funding priorities are off kilter. The Biden budget projects business systems outlays to be lower in 2033 than today, yet the needs for new technology will likely remain high. Also, taxpayer services need major improvements: one recent survey ranked the IRS last among 221 private companies and public agencies on customer service.4

The SOP says that added taxpayer services and technology funding will be needed above the IRA amounts.5 It discusses improvements to taxpayer services and business systems over 68 pages of text, but it discusses enforcement over just 17 pages.6 Despite this emphasis, enforcement received the lion’s share of IRA funding.

Congress should consider rebalancing IRS funding away from enforcement and toward taxpayer services and business systems.

Return on Investment

The Congressional Budget Office expects the $79 billion boost to IRS funding to raise $180 billion over 10 years.7 Supporters say this indicates a high “return on investment” from the funding, and thus a beneficial policy change.8 But that only considers the government’s gain. Instead, policymakers should consider the overall costs and benefits to society.

Consider the costs. They include the $79 billion for the IRS and possibly higher private-sector compliance costs, which may be about 10 percent of the revenues raised.9 Costs may also include deadweight losses from taxpayers changing their behavior in ways that undermined output, such as reducing work and investment. Increased enforcement can also generate hard-to-quantify costs such as taxpayer anguish, financial uncertainty, and losses of civil liberties.

Now consider the benefits. The government will raise a net $101 billion for added spending, but that will likely displace private-sector spending. Thus, policymakers need to consider whether the added spending they envision is worth more than the private spending displaced plus the costs of raising the revenue.

Improvements in taxpayer services and business systems could reduce taxpayer costs, increase IRS accuracy, and boost compliance with the law. Thus, the more funding going toward these activities, the more likely there will be a win-win for taxpayers and the government. The National Taxpayer Advocate argues that “the most efficient way to improve compliance is by encouraging and helping taxpayers to do the right thing on the front end. That is much cheaper and more effective than trying to audit our way out of the tax gap one taxpayer at a time on the back end.”10

By contrast, more aggressive IRS enforcement would increase taxpayer costs, as they would invest more time and energy defending themselves. The IRS would catch some additional tax cheats, but law-abiding taxpayers would face collateral damage.

Collateral damage would result because the IRS makes many errors, which is not surprising given the complexity of the tax code. The issues at dispute are often gray, as illustrated by litigation statistics, which show that the IRS wins only about half the time.11 For Tax Court and refund cases closed over the past five years, the IRS on decision gained just 48 percent of the dollars in dispute.

Similarly, IRS auditing imposes collateral damage because many audited taxpayers have paid the correct amount. For example, between 40 to 50 percent of partnership audits result in no recommended changes.12 For individuals earning more than $5 million, the audit no-change rate is just under 40 percent.13 Given that audits are often targeted by IRS algorithms and discrepancies, these percentages seem quite high. Recommended changes can be wrong and may be appealed. Tax litigation expert Daniel Pilla believes that more than half of IRS audit results are incorrect.14

The IRS and the Biden administration promise to focus increased enforcement on high-earning households. Interestingly, IRS data show that tax recommended on audits is higher relative to income for middle-income returns than for high-income returns. For audits with recommended changes, the changes average roughly 5 to 8 percent of income for middle-income taxpayers but just 1 to 3 percent of income for high earners.15 High-earning taxpayers are more likely to receive expert tax advice, and thus less likely to make errors.

Of course, the IRS needs to enforce the tax laws, as enforcement deters cheating. But there are downsides to increased enforcement, including higher compliance costs, higher deadweight losses, and added stress and uncertainty for families and businesses. With more aggressive enforcement, taxpayers who are already paying the correct amount will need to expend time and energy defending themselves. And because the IRS is such a powerful agency, aggressive tax enforcement can put civil liberties at risk.16

Federal Tax Gap Stable

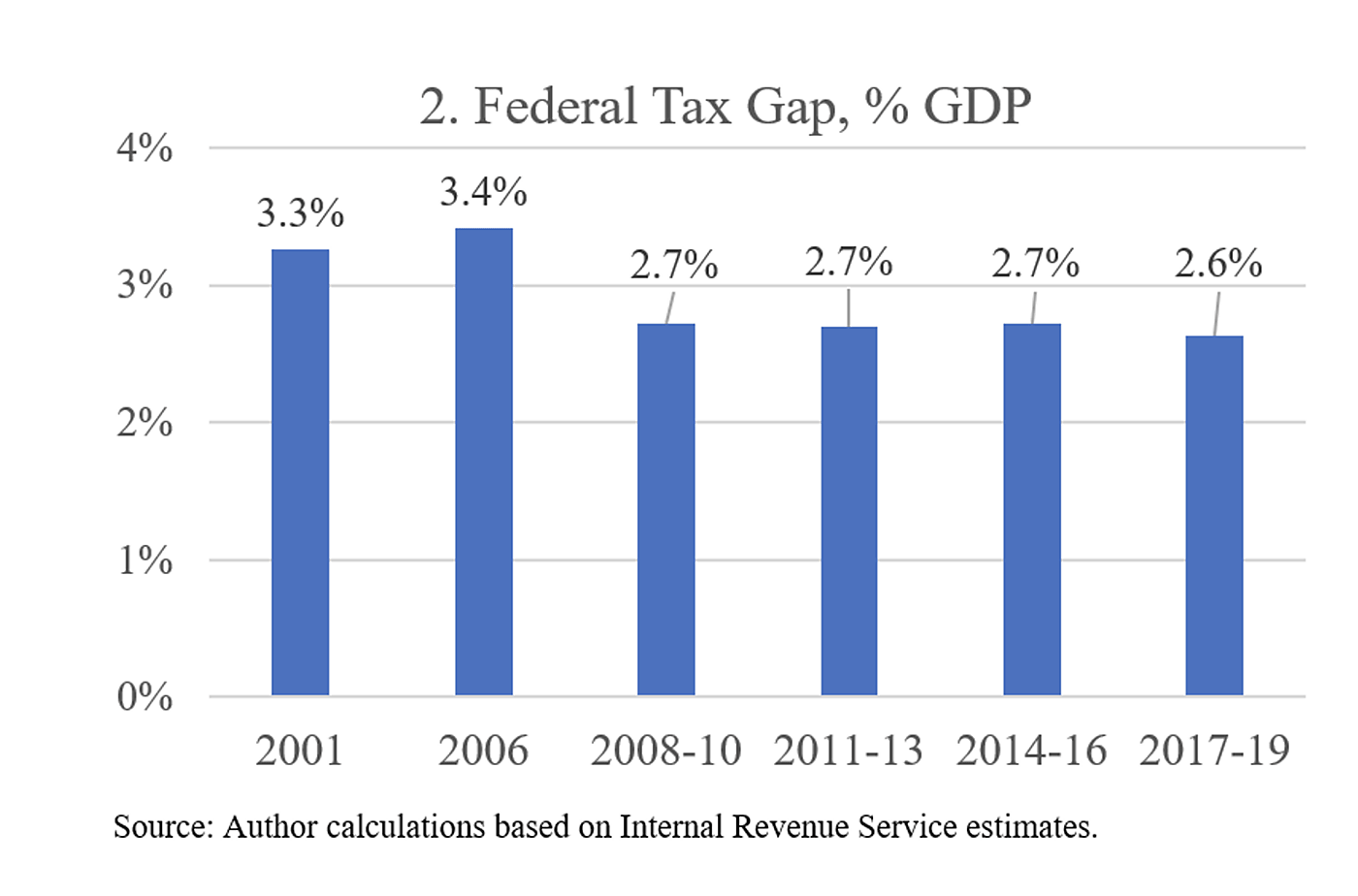

Last year, the IRS released a new estimate of the “tax gap,” which is the amount of federal taxes owed but not paid.17 The average gross tax gap for 2014–2016 was $496 billion, and after late payments and enforcement the net gap was $428 billion. The report includes tax gap estimates for prior years and a projection for 2017–2019.

The dollar value of the tax gap has increased over time, but the gap has not increased when compared to the nation’s gross domestic product (GDP), as shown in Figure 2.18 Despite the decline in audit rates, the tax gap dipped from 3.3 percent of GDP two decades ago to 2.6 percent more recently. The degree to which Americans are law-abiding on federal taxes does not appear to have changed much over time.

U.S. and Foreign Tax Gaps

International studies show that the U.S. tax gap is not high compared to other advanced economies. Our federal tax gap is 2.6 percent of GDP, and if we assume the same nonpayment rate for state-local taxes, the overall U.S. tax gap is about 4.0 percent of GDP.19 That figure may be compared to other countries.

- In a 2018 study, Konrad Raczkowski and Bogdan Mroz estimated that the tax gap for the United States was 3.8 percent of GDP and the gap for 28 European Union (EU) countries was 7.7 percent of GDP.20

- In a 2015 study, Konrad Raczkowski estimated that the tax gap for 28 EU countries was 10.7 percent of GDP.21

- In a 2019 study, Richard Murphy estimated that the tax gap for 28 EU countries was 5.6 percent of GDP.22

However, the overall EU tax burden is higher than the U.S. burden. If we adjust the EU gap estimates down using the ratio of U.S. to EU taxes, the EU gap estimates are 5.1 percent for Raczkowski‐Mroz, 7.1 percent for Raczkowski, and 3.7 percent for Murphy.23 These figures are still similar or higher than the U.S. gap. However, there are a few advanced economies that have published detailed gap estimates that are lower than the U.S. gap.24

The above bulleted studies are based on measures of shadow economies, which generally means otherwise legal activities that escape taxation. Here are two further studies:

- In a 2018 study across 158 countries, Leandro Medina and Friedrich Schneider found that the U.S. shadow economy is the second smallest as a percent of GDP.25 From 2010 to 2015, the U.S. shadow economy of 7.7 percent compared to the European average of 20.2 percent.

- In a 2016 study across 157 countries, Mai Hassan and Friedrich Schneider estimated that the U.S. shadow economy was 8.3 percent of GDP in 2013 and the EU’s was 23.1 percent.26

These sorts of estimates should be considered rough. Also, they overstate revenues that might be gained from enforcement if they do not account for behavioral responses.27 For example, if the IRS were to squeeze more money from businesses, some would cut hiring and investment, which would reduce the revenues raised.

Better Ways to Boost Tax Compliance

The IRA boosted enforcement spending to improve compliance, but there are three better ways to boost compliance that would benefit taxpayers and the economy.

First, keeping taxes low to reduce incentives for cheating. Discussing international studies, Hassan and Schneider note, “It is widely accepted in the literature that the most important cause leading to the proliferation of the shadow economy is the tax burden. The higher the overall tax burden, the stronger are the incentives to operate informally in order to avoid paying the taxes.”28

Second, improving taxpayer services, technologies, and employee training at the IRS, which would reduce filing and audit errors. The National Taxpayer Advocate said, “Tax compliance depends on prompt, high-quality customer service, and when compliance becomes unduly burdensome, the IRS runs the risk that taxpayers will simply quit trying.”29

Third, simplifying the tax code. Rising complexity is an invitation for errors and abuse. In a 2022 report on IRS audits, the Government Accountability Office found, “Since fiscal year 2010, average audit hours have more than doubled for returns with income of $200,000 and above.”30 That statistic likely reflects the rising complexity of the code.

In 2012, the National Taxpayer Advocate said that tax code complexity “facilitates tax avoidance by enabling sophisticated taxpayers to reduce their tax liabilities and by providing criminals with opportunities to commit tax fraud.”31 She concluded that tax reforms to simplify the code would “reduce the likelihood that sophisticated taxpayers can exploit arcane provisions to avoid paying their fair share of tax; enable taxpayers to understand how their tax liabilities are computed and prepare their own returns; improve taxpayer morale and tax compliance.”32

Unfortunately, Congress has not heeded the NTA’s advice. The IRA, for example, added 20 or so new and expanded energy tax breaks, many with complicated rules. The SOP says the energy provisions will cost $3.9 billion to administer, and they will surely generate enforcement problems. The new breaks will also boost costs for planning, compliance, and lobbying in the private sector since $1 trillion in benefits are at stake.33

The number of official tax expenditures has risen from 53 in 1970 to 205 today, making the IRS’s administration and enforcement job ever more difficult.34 We know from experience that complex tax expenditures, such as the low-income housing tax credit, generate substantial errors and abuse.35 So tax simplification to eliminate special breaks would reduce the tax gap and reduce IRS costs for administration and enforcement.

Conclusions

IRS estimates show that the tax gap is not rising relative to the size of the economy, and the U.S. tax gap appears to be modest by international standards. Nonetheless, policymakers can reduce the tax gap by reducing tax rates, improving IRS services and efficiencies, and simplifying the tax code. Those policies would be a win for taxpayers, the government, and the economy.

The National Taxpayer Advocate recently argued that IRA funding “is disproportionately allocated for enforcement activities, and I believe Congress should reallocate IRS funding to achieve a better balance with taxpayer service needs and IT modernization.”36 That seems right, and so a compromise between House and Senate may be to shift some of the enforcement increases to taxpayer services and business systems.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.