Chairman Kelly, Ranking Member Thompson, and Members of the Subcommittee: Thank you for inviting me to testify today.1

I will make two main points in my remarks and conclude with thoughts on how U.S. policy should respond to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) Two Pillar proposal:

First, the OECD once served an important role in coordinating international tax systems to reduce the double taxation of income, which facilitated trade and investment. In recent decades, the OECD’s mission has shifted towards protecting a government-centric economic model, perverting the principles on which it was founded. This has manifested in the OECD’s Two Pillar proposal to seize sovereignty over tax law away from elected governments around the world, increase corporate tax rates, raise new revenues, and redistribute taxing rights from productive economies to consumer economies.

Second, the Two Pillar proposal is particularly costly for the United States. Estimates indicate that the OECD tax increases will likely reduce U.S. revenue, primarily target American firms, and shrink domestic investment and jobs. By working with the OECD and signing on to the plan, the Biden administration is actively circumventing Congress’ constitutional authority over tax rules and giving away Congress’ ability to set pro-growth tax policy independently.

Congress should withdraw from the OECD and reclaim its constitutional power to set U.S. tax policy. The most powerful message and economically beneficial response would include cutting the corporate tax rate to 15 percent or lower, making full expensing permanent, and finishing the 2017 conversion to an entirely territorial system.

The OECD Two Pillar Approach

In October 2020, the OECD released an outline for a “Two-Pillar” approach to remaking the international tax system—nearly 140 countries have signed on, or at least their executive branches have, including the Biden administration.2 The proposals are intended to change the taxation of multinational businesses by raising effective tax rates, allowing certain kinds of corporate welfare, and reallocating taxing rights away from some countries to others. Pillar One aims to change where some companies pay taxes, very selectively moving toward a system based on customer location instead of business activities. Pillar Two includes a series of new rules that enforce a global minimum tax of 15 percent.

Pillar One would reallocate an estimated $130 billion to $200 billion of large multinational corporate profits to countries where customers are located and from where the firms have a physical and productive presence.3 This is done with a complicated formula based on a company’s sales, marketing, and distribution in each jurisdiction. Amount A of Pillar One, applies to companies with more than €20 billion in revenues (falling to €10 billion after seven years) and a global profit margin above 10 percent. Amount A is intended to replace a patchwork of digital services taxes, which some countries have begun charging to large technology firms based on revenue and users in their country.

Pillar One also includes Amount B, which could provide a more formulaic transfer pricing method for marketing and distribution. On July 12, 2023, the OECD announced an agreement on an outcome statement indicating additional progress on finalizing details of Amount A and further work on Amount B. However, the full agreement on Pillar One is still being negotiated, and many specifics remain subject to disagreements between countries.4 As Members of Congress, you should request the Administration share the existing drafts of these documents.

Pillar Two comprises five primary new rules that work together to enforce a global minimum tax rate of 15 percent on businesses with more than €750 million in revenues. Pillar Two is estimated to raise about $220 billion in global tax revenue.

The qualified domestic minimum top-up tax (QDMTT) is an alternative minimum tax to allow countries first right to tax their domestic entities at a 15 percent rate on a novel tax base defined by the OECD. The income inclusion rule (IIR) requires parent companies to include in their taxable income the profits of their foreign subsidiaries that have not been taxed at the minimum 15 percent rate.

The under-taxed profits rule (UTPR) allows countries to increase taxes on a business if a related entity in another jurisdiction pays a tax rate below 15 percent. The UTPR creates a backstop for the QDMTT by allowing foreign countries to tax firm profits in other countries if tax rates are lower than the OECD minimum rate. Taxing rights are distributed using a formula if multiple countries make assessments under the UTPR.

The final two components include the denial of tax treaty benefits to companies in non-compliant jurisdictions (called the subject to tax rule (STTR)) and anti-base erosion reporting rules on corporate structure, county-by-county income, taxes paid, and around 150 other similar data points.5 The agreement mandates that tax authorities automatically exchange this private corporate financial data, including in the technology and defense sectors, with governments worldwide, many corrupt and hostile to Western countries.

The in-scope firms are largely U.S.-based businesses. By one estimate, U.S. companies make up 46 percent of in-scope Pillar One firms, representing 58 percent of profits redistributed under Amount A.6 The rules proposed by the OECD are a dramatic departure from both the agreed-upon current international tax system and the principle that countries have sole sovereignty over domestic activities. For policymakers and businesses alike, they pose more questions than answers.7 Ultimately, these rules are primarily intended to undermine national sovereignty over tax law, grab revenue from the United States, and reduce the competitiveness of American workers and companies.

Myth of Race to the Bottom: Tax Rates Down, Revenue Up

The OECD aims to remake the international corporate tax system in response to what it terms base erosion and profit shifting (BEPS) by multinational businesses. The reforms are based on the premise that tax competition between countries has resulted in a “race to the bottom” that will “ultimately drive applicable tax rates on certain mobile sources of income to zero for all countries, whether or not this was the tax policy a country wished to pursue.”8 The OECD overstates this dynamic, but tax competition for global businesses and talent benefits free trade and free movement. It often leads to more business investment and employment and better overall economic policies by constraining the government’s ability to pursue policies that drive people and businesses from their borders.9

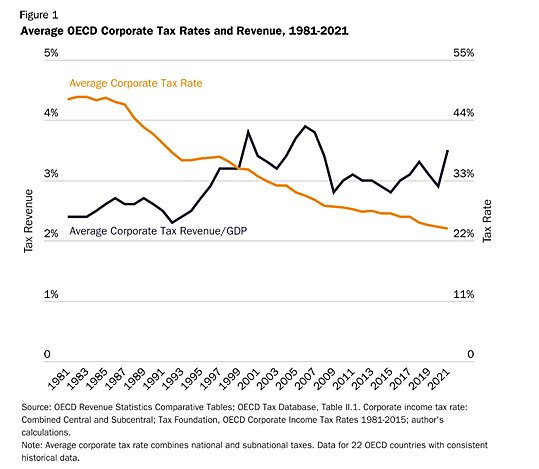

So, has the dreaded race to the bottom resulted in starving governments of corporate tax revenue? Data from the OECD shows that tax revenue has trended up, not down, over time. Figure 1 shows that corporate tax revenue as a share of the economy has increased from 2.4 percent in 1981 to 3.5 percent in 2021 across 22 OECD countries, for which we have consistent data. Similarly, corporate tax revenue as a share of all revenue has also trended up since the 1980s.

The solid corporate tax receipts during this period are even more impressive given that the average corporate income tax rate across the same OECD countries was cut in half, falling from about 48 percent in the early-1980s to 24 percent in 2021. Tax competition has not yet eroded tax revenue in the United States or the OECD. With base-broadening in some countries, lower rates have resulted in higher corporate revenue.

The OECD Shifts From Growth to Redistribution

The myth of race to the bottom and tax harmonization to stop it has been the elusive task of the OECD since the early 1980s, but fundamentally changing the international tax system and advocating for “whole-of-government strategies” to meet ever-changing economic, environmental, and social goals was not always its focus. The OECD was established in 1961 to preserve individual liberty and increase general well-being through expanded trade and international investment.10

As global trade increased through the 1950s, multiple countries claimed the same corporate profits, leading to double taxation and creating obstacles to international trade. In 1963, the OECD published its Draft Model Convention on Income and Capital, an ambitious model treaty to resolve the problem of double taxation.11 Coordinating tax systems to address double taxation was the primary tax mission of the OECD for its first three decades.

Every country’s tax system is unique. Given different tax codes across countries, businesses should be expected to use these differences to lower their tax burdens. In the late 1970s and 1980s, the growth of global trade and more sophisticated financial products allowed firms to more efficiently plan their taxes, increasing tax competition between governments. Firms that successfully minimize their tax burden across two or more countries often find a way to exempt some portion of their profits from taxation. This has been termed “double non-taxation” or “nowhere income.” This income—and the connected economic activity—is often not actually stateless but actively courted by governments with low or no corporate income tax.

Competition for investments, business activity, and jobs is a foundational characteristic of jurisdictional diversity. Countries compete on innumerable margins, including resources, workforce characteristics, infrastructure, regulatory costs, rule of law, and state subsidies. Whether a business moves between tax jurisdictions for a better-educated labor force or a more friendly tax code, the effect on the tax base is the same, shrinking in one place and expanding in another. Given the myriad margins on which countries compete for global investment, it is peculiar to single out tax rates as a margin on which governments should not compete. However, stopping the legal means of lowering tax burdens has been the increasing focus of the OECD through various projects on tax havens, tax competition, and base erosion and profit shifting.

A 1981 Carter Administration’s U.S. Treasury report on Tax Havens and Their Use by United States Taxpayers (the Gordon Report) launched what has metastasized at the OECD as successive projects to increase taxes on international business.12For example, in 1998, the OECD released a report on international tax competition that marked a distinct shift from the OECD’s previous work.13 The report, titled Harmful Tax Competition, concludes that taxes should not be used to attract business investments and that tax competition “may hamper the application of progressive tax rates and the achievement of redistributive goals.”14

The OECD’s tax work shifted from primarily working to coordinate tax systems to eliminate double taxation to proposing ever more complicated new tax systems and reporting requirements to ensure every dollar is taxed equally. In a 2012 tax law journal article, Andrew Morriss and Lotta Moberg characterize the OECD’s campaign against tax competition as the organization’s effort to form an international tax cartel run by a special interest group of tax collectors.15 Recent events make Morriss and Moberg’s argument quite prescient—the OECD’s Two-Pillar proposal allows the organization to decide the global tax rate and redistribute taxing rights from one country to another.

It is worth noting that U.S. policymakers are not without blame. Often the OECD builds and encourages other countries to adopt the worst tax ideas that originate in the United States. For example, the United States was the first mover in expanding Controlled Foreign Corporation rules to unrealized foreign income in the 1960s and again through Global Intangible Low Tax Income (GILTI) in 2017. The U.S. Foreign Accounts Tax Compliance Act (FATCA), a law that coerces the sharing of international taxpayer information, also spawned the OECD’s Multilateral Competent Authority Agreement on Automatic Exchange of Financial Account Information, which has been called the “treaty to end financial privacy.”16

OECD shifts the goalposts, again

In the early-2010s, the OECD primarily worked to eliminate double non-taxation to ensure higher global effective tax rates on corporate income. The OECD’s most recent proposals add a new dimension: centralized reallocation of taxing rights. Pillar One and UTPR are primarily about redistributing existing taxing rights from the countries where the productive activity occurs to countries where goods and services are sold.

Most countries already have consumption-based value-added and sales taxes. If governments want to raise revenue based on consumption, they already have purpose-built tools to meet that goal. Turning part of the corporate income tax into a type of sales-apportioned gross receipts tax betrays the political motives of the project. OECD research from 2008 concludes that “corporate taxes are found to be most harmful for growth,” compared to value-added taxes and income taxes—a result that should lead to policies that reduce rather than raise the burden of business taxes.17 As is clear from the politics of digital services taxes or GAFA taxes (Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon), which Pillar One is designed to effectively replicate, domestic European politics incentivizes taxing the most profitable American companies simply because they are American and successful.

OECD mission creep

The OECD’s work has served a valuable role in facilitating greater trade and access to capital markets among market-oriented democratic member states and non-member developing countries. This politically neutral work has been unambiguously good for individual liberty and increased general well-being, meeting the OECD’s founding mission. However, as I’ve written before with colleagues, “today’s OECD has largely devolved into a taxpayer-funded advocacy group for higher taxes, more intrusive government, burdensome regulation, and climate activism.”18 The OECD’s recent work spans numerous projects that recommend very progressive, primarily government-centric interventions in labor markets, housing markets, and private associations.19 Similarly, their work on inequality and mobility suggests higher inheritance and wealth taxes as an important way to “affect social mobility,” advancing the politics of tearing successful people down rather than creating opportunities for the poor.20 The OECD has indicated that worldwide rules on the taxation of individuals are the next step in order to prevent high-income individuals from escaping high tax rates by moving to countries with low tax rates.21

The OECD has also expanded its work on climate policy. In 2016, it created the Centre on Green Finance and Investment to support the transition to a “green, low-emissions and climate-resilient economy.22 The OECD’s Environment Directorate recently launched a new Inclusive Forum on Carbon Mitigation Approaches (IFCMA) based on the inclusive framework model used in the Two Pillar process. The OECD sees carbon leakage—the incentive carbon emitters have to move production to jurisdictions with fewer limits on emissions—as similar to the problem of double non-taxation.23 Its solution is a centralized multilateral tool to ensure that every country meets the OECD’s climate goals. The problem is not the transition to cleaner energy and manufacturing; the problem is OECD’s anti-market tools that require “broader whole-of-government strategies” to achieve their one-size-fits-all climate goals.24

American Workers and the Economy

It is widely acknowledged, including by the OECD, that higher taxes under the Two Pillar proposal will reduce investment and shrink global GDP.25 Because a significant share of the businesses targeted are U.S. firms, domestic investment and American works will face non-trivial economic costs.

Ernst and Young estimates that widespread adoption of Pillar Two outside of the United States could increase the effective tax rate on U.S. multinationals by 2.6 percentage points. The tax rate on foreign income rises by 4.5 percentage points, and the domestic income tax rate increases by 1.4 percentage points. These higher tax rates are estimated to reduce U.S. jobs by about 370,000 (a 1.5 percentage point reduction) and cut annual investment by roughly $22 billion (a 2.4 percentage point reduction). The estimates show that job and investment reductions could be as high as 5 percentage points, representing a significant risk to the American economy.26 The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development similarly estimates that Pillar Two will reduce foreign direct investment flows by about 2 percent, giving a range of 1.2 percent to 4 percent.27

These estimates reflect the complementarity of foreign and domestic investment. Research consistently finds that when multinational businesses invest abroad, they also increase investment at home. For example, Mihir Desai, C. Fritz Foley, and James Hines find that “one dollar of additional foreign capital spending is associated with 3.5 dollars of additional domestic capital spending.”28 The same is true for investments in low-tax countries. Increasing effective tax rates on multinational investments in tax havens reduces both local investment and the connected and complementary investments elsewhere in the world.29

Following an effective tax rate increase on income originating in U.S. territories similar in magnitude to the EY estimated increases in effective tax rates on foreign income, Juan Carlos Suárez Serrato finds firms operating in Puerto Rico and exposed to the tax increase “reduced their US employment by 6.7%.” Areas of the United States that had more firms affected by the change “experienced relative decreases in income, wages, and home values, and these areas also became more reliant on government transfers.”30 Cutting off access to low-tax foreign investments by implementing the OECD’s international tax increases will likely reduce affiliated domestic economic activity, harming U.S. workers.

Sovereignty and the U.S. Tax Base

The Biden Administration has used the OECD as an extra-legislative venue to advance policies that do not have congressional support. By working with the OECD to develop their Two-Pillar approach and agreeing to the proposed outline for the new rules, the Administration has effectively sidelined Congress to upend decades of international tax norms. Even more problematic, the OECD plan does not have buy-in among members of the President’s own party. In direct refutation of the OECD process, Congress passed an OECD non-compliant U.S. 15 percent corporate alternative minimum tax (CAMT) as part of the Inflation Reduction Act in 2022.

We cannot know the true goals of the Treasury’s negotiators. Still, the outcomes of the OECD process certainly indicate that little consideration was given to Congress, the U.S. tax base, U.S. employers, or American workers. The negotiators have undermined the U.S. constitutional order by colluding with foreign powers and non-governmental organizations to tax Americans because Congress does not want to enact the Administration’s preferred tax policies. Two significant results in the OECD proposal indicate that U.S. interests were poorly represented.

First, the Pillar Two minimum tax is conceptually similar to components of the 2017 tax reform’s international rules, most notably GILTI. There could have been a path by which GILTI was included as Pillar Two compliant, likely as a QDMTT or IIR. However, GILTI is disfavored in the OECD ordering rules, leaving U.S. firms with additional complexity and giving other countries first right to tax U.S. firms’ low-tax foreign income. Without U.S. legislative reforms, Treasury has two bad options, recognize foreign taxes paid on top-up taxes (undermining U.S. revenue from GILTI) or deny related foreign tax credits and open U.S. firms up to widespread double taxation.

Second, UTPR’s 15 percent effective tax rate calculation disfavors U.S.-style non-refundable tax credits compared to refundable credits and direct subsidies. Non-refundable credits lower taxes paid, lowering effective tax rates. Direct subsidies also lower effective tax rates but much less because they show up as income. For example, if a firm makes $100 in profit, pays $16 in taxes, and receives a $5 government subsidy, the firm’s post-subsidy effective tax rate is 11 percent if the subsidy is provided as a non-refundable credit, but the effective tax rate is just above 15 percent if the subsidy is a direct payment. In this scenario, the firms are economically identical. However, using the U.S.-style credit will push the effective tax rate below the OECD minimum, triggering additional taxes, while the direct subsidy does not.

These two outcomes partly drive recent Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) estimates which show the United States could lose more than $122 billion in tax revenue if other countries implement Pillar Two and the U.S. does not. Under the scenario in which Congress concedes to the OECD and implements its international tax rules, the U.S. still collects about $57 billion less over nine years. JCT explains that their estimates are highly uncertain because other countries’ adoption of the new rules is unclear and behavioral responses of multinationals are hard-to-estimate.31 Tax reporter Alex Parker also notes that “the OECD allows for a lot of leeway in how the domestic minimum taxes can be designed and implemented. Countries will surely want to look for new ways to grab foreign income, especially if it’s coming from U.S. companies.”32 Redistributing taxing rights creates winners and losers, and the U.S. will likely lose.

This tension is even more significant in Pillar One, which would explicitly reallocate about $130 billion in corporate profits each year under Amount A, according to OECD estimates.33 Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has written, without evidence, that Pillar One “will be largely revenue neutral for the United States.”34 However, if more than half of in-scope profits are from U.S. companies, it stands to reason that a significant share of the $130 billion in redistributed profits will be redistributed away from the U.S. tax base, further eroding Treasury’s revenue collections.

Competition on the wrong margin

The OECD’s project will likely not reduce governments’ incentive to attract new businesses and expand their tax bases. It will simply shift the margins on which this competition will take place. By setting the tax rate at 15 percent and defining a tax base that denies certain types of tax credits, competition will shift to other kinds of subsidies.

Compared to many other countries, the United States provides comparatively few direct cash or cash-equivalent subsidies to private businesses. When Congress or U.S. states subsidize companies, they tend to do so with non-refundable tax credits, reduced tax rates, and deductions. These incentives offset tax liabilities but do not constitute direct payments from the Treasury. For example, the research and development tax credit subsidizes targeted activity by reducing federal corporate income tax payments by $32 billion annually, but it does not constitute direct payments to U.S. firms.

Pillar Two will not eliminate state-subsidized corporations, it will simply shift competition from the economically more neutral competition over tax rates, to competition over tax subsidies and other corporate welfare. Some countries have already begun reforming their fiscal system in response to the OECD’s proposal. For example, Reuters reports that Vietnam is considering ways to directly compensate Samsung and other foreign companies for the higher taxes they will be forced to pay under the new 15 percent minimum rate.35 A similar dynamic is at play in Switzerland.36 Other tax havens are also likely to impose the new taxes to raise enough revenue to fund other fiscal subsidies to continue attracting businesses. The only substantive change for many countries will be a shift to a less efficient and more corruption-prone system of government favoritism.

The U.S. Response

The OECD has proven it no longer serves the interests of the United States and has abandoned its founding mission to promote international economic growth. Therefore, Congress should withdraw from and stop financially supporting the OECD and reform our domestic tax laws.

First, Congress should instruct the President to immediately notify the depository government (the government of France) under Article 17 of the Convention on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development that the United States will terminate the application of the Convention and the Convention’s Protocols. Withdrawal from the OECD should be paired with a prohibition on any U.S. funding for the OECD in future budgets. The House and the Senate should adopt the House Appropriations Committee’s recent spending bill, which zeroed out OECD funding following the recommendation of 10 House Republicans on the Ways and Means Committee.37 The United States currently funds 19.1 percent of the OECD’s general Part 1 budget, more than double the next largest contributor.38 U.S. should work to advance the OECD’s original mission of free trade, international investment, and individual liberty.

Second, Congress should make America the most attractive place to do business in the world. The Tax Foundation ranks the United States 22nd out of 38 countries on international corporate tax competitiveness.39 Even after the 2017 tax cut, the United States still has an above-average corporate income tax rate, and full expensing for domestic investments is in the process of expiring.40

To benefit American workers and undercut the OECD project by making the United States a more attractive place to do business, Congress should lower the corporate tax to the OECD and Biden Administration’s agreed-upon rate of 15 percent and make full expensing for all new U.S. investments permanent, including structures. Rather than adopting the OECD foreign tax rules, Congress should finish converting the U.S. corporate tax to a full territorial system that entirely disregards both foreign profits and foreign taxes. Short of eliminating the corporate income tax—also a worthy goal—this would allow the U.S. to decouple from the OECD tax cartel.

Congress should also increase financial privacy protections, prohibit the automatic exchange of taxpayer information with other countries, further limit the deduction for interest expense, and cut the capital gains tax rate.41 These reforms would ensure that more multinational firms shift their low-tax profits to the United States. Compared to the status quo, in which the United States is set to lose as much as $122 billion in tax revenue, a true territorial system is not necessarily a significant revenue loss.

The most powerful message Congress could send is to play the game the OECD is trying to stop. Making the United States an international tax haven is better than engaging in retaliatory measures. The United States is big enough and powerful enough to stand up and reject the plan Secretary Yellen and President Biden are trying to force on Congress.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.