Chairmen Pfluger and Higgins, Ranking Members Magaziner and Correa, and distinguished members of the subcommittees, thank you for the opportunity to testify. My name is Alex Nowrasteh, and I am the Vice President for Economic and Social Policy Studies at the Cato Institute, a nonpartisan public policy research organization in Washington, D.C. It is an honor to be invited to speak with you today on the topic: “Beyond the Border: Terrorism and Homeland Security Consequences of Illegal Immigration.”

Over many decades, the Cato Institute has produced original research on the benefits of immigration to Americans, the problems of illegal immigration and chaos along the southwest border caused by the restrictive legal U.S. immigration system, and sober evaluations of the realistic hazard of foreign-born terrorism. In my research, I use a broad definition of terrorism: the threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by non-state actors to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation.1 Drug cartels and other criminal organizations are not terrorists even though they commit heinous crimes, murder many people, destroy much more property, and injure more innocent people. Terrorism is not synonymous with “bad crimes.” It is a specific type of crime based on the motivations of the criminal.

Foreign-born terrorists who seek to commit attacks on U.S. soil pose a hazard to the life, liberty, and private property of Americans and the lawful operation of the U.S. government. Reducing the risk of foreign-born terrorism is a legitimate function of the U.S. government. Nonetheless, terrorism committed by foreign-born attackers is a manageable hazard. The threat of terrorist entry through the southwest border is minuscule even when compared to the overall low hazard posed by foreign-born terrorism. This fact could always change because the future is unknowable, but available information indicates that foreign-born terrorists who seek to cross the U.S.-Mexico border and commit an attack here pose a very small and manageable threat.

Illegal Immigrants, Asylum Seekers, and Foreign-Born Terrorism on U.S. Soil

In my research, I have identified 230 foreign-born terrorists who committed attacks on U.S. soil, intended to commit attacks on U.S. soil, threatened attacks here, or tried to fund domestic terrorism.2 Those 230 foreign-born terrorists were responsible for 3,046 murders and 17,078 injuries in attacks on U.S. soil from 1975 through the end of 2023.3 The annual chance of being murdered in a terrorist attack committed by a foreign-born terrorist during that time is about 1 in 4.5 million per year.4 The annual chance of being injured in such an attack is about 1 in 793,561 per year. By comparison, the annual chance of being murdered in a criminal non-terrorist homicide in the United States was about 1 in 13,767 during the same period. The chance of being murdered in a normal homicide is about 323 times greater than being killed in an attack committed by a foreign-born terrorist.5 During that time, 97.8 percent (2,979) of all those murdered in terrorist attacks were murdered on 9/11, and 86.9 percent (14,842) percent of all people injured in foreign-born terrorist attacks were injured on 9/11.

Zero people were murdered in attacks on U.S. soil committed by a foreign-born terrorist who entered illegally during the 1975–2023 period. Zero people were injured in attacks on U.S. soil committed by a foreign-born terrorist who entered illegally during that time. Suffice it to say, the number of people killed or injured in a terrorist attack committed by an illegal immigrant who entered illegally across the U.S.-Mexico border is also zero.

However, nine foreign-born terrorists entered the United States illegally during the 1975–2023 period (Table 1). Three of the nine terrorists entered illegally by crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. They are Dritan Duka, Eljvir Duka, and Shain Duka, and they entered illegally in 1984 when they were aged 5, 3, and 1, respectively. They were arrested almost 23 years later, in 2007, while plotting to attack Fort Dix, New Jersey. The Duka’s plot was not serious. They were arrested after a video clerk saw a VHS recording that the brothers taped of themselves acting as terrorists.6 Of the other illegal immigrant terrorists, five illegally crossed the U.S.-Canada border (Kabbani, Thurston, Mezer, Ressam, and Abdi) and one was a stowaway on a ship (Meskini).

The Duka brothers were “gotaways,” which is defined as an unlawful border crosser who (1) is directly or indirectly observed making an unlawful entry into the United States; (2) is not apprehended; and (3) is not a turn back.7 There have been many gotaways in recent years, over 1.7 million since January 2021. There is little evidence that a larger population of illegal immigrants in the United States, a population augmented by more gotaways, poses an increased risk of terrorism. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) should be vigilant to the possibility, the situation could always change, and an illegal immigrant could commit an attack, but there is little reason to worry more than usual.8

Thirteen terrorists entered as asylum applicants, and they are responsible for 9 murders and about 669 injuries in attacks on U.S. soil during the 1975–2023 period. The annual chance of being murdered by a foreign-born terrorist who entered as an asylum applicant or who was granted asylum shortly after entering is about 1 in 1.5 billion per year. The annual chance of being injured in an attack committed by a foreign-born terrorist who was present as an asylum seeker is just over 1 in 20 million per year. None of the asylum seekers who became terrorists entered by crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. Only one was from the Western Hemisphere; Eduardo Arocena from Cuba, and he committed his last attack in 1980.9

Table 1

Name of Terrorist | Year | Fatalities | Injuries | Immigration Status Upon Entry | Country of Birth | Ideology |

Kabbani, Walid |

1987 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Illegal Immigrant |

Lebanon |

Foreign Nationalism |

Thurston, Darren |

1996 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Illegal Immigrant |

Canada |

Left |

Mezer, Gazi Ibrahim Abu |

1997 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Illegal Immigrant |

Palestine |

Islamism |

Meskini, Abdelghani |

1999 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Illegal Immigrant |

Algeria |

Islamism |

Ressam, Ahmed |

1999 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Illegal Immigrant |

Algeria |

Islamism |

Abdi, Nuradin M. |

2003 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Illegal Immigrant |

Somalia |

Islamism |

Duka, Dritan |

2007 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Illegal Immigrant |

Macedonia |

Islamism |

Duka, Eljvir |

2007 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Illegal Immigrant |

Macedonia |

Islamism |

Duka, Shain |

2007 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Illegal Immigrant |

Macedonia |

Islamism |

Arocena, Eduardo |

1980 |

2.00 |

0.00 |

Asylum |

Cuba |

Right |

Berberian, Dikran Sarkis |

1982 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Asylum |

Lebanon |

Foreign Nationalism |

Yousef, Ramzi |

1993 |

1.00 |

173.67 |

Asylum |

Pakistan |

Islamism |

Ajaj, Ahmed |

1993 |

1.00 |

173.67 |

Asylum |

Palestine |

Islamism |

Khan, Majid Shoukat |

2003 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Asylum |

Pakistan |

Islamism |

Siraj, Shahawar Matin |

2004 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Asylum |

Pakistan |

Islamism |

Ferhani, Ahmed |

2011 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Asylum |

Algeria |

Islamism |

Tsarnaev, Dzhokhar |

2013 |

2.50 |

140.00 |

Asylum |

Kyrgyzstan |

Islamism |

Tsarnaev, Tamerlan |

2013 |

2.50 |

140.00 |

Asylum |

Kyrgyzstan |

Islamism |

Fathi, El Mehdi Semlali |

2014 |

0.00 |

0.00 |

Asylum |

Morocco |

Islamism |

Rahimi, Ahmad Khan |

2016 |

0.0 |

29.0 |

Asylum |

Afghanistan |

Islamism |

Artan, Abdul Razak Ali |

2016 |

0.0 |

13.0 |

Asylum |

Somalia |

Islamism |

Shihab, Shihab Ahmed Shihab |

2022 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

Asylum |

Iraq |

Islamism |

Source: Alex Nowrasteh, Terrorism and Immigration A Risk Analysis, 1975–2023.

Abdulahi Hasan Sharif is the closest example of a possible asylum seeker or illegal immigrant having crossed the U.S.-Mexico border and then committing an attack. He crossed the U.S.-Mexico border in 2011 and was immediately apprehended by Border Patrol. He may have possibly applied for asylum, but an immigration judge ordered him to be removed, and Sharif never appealed that decision. Instead, he went to Canada and wounded five people years later in a vehicle attack in Edmonton in 2017.10

Note on Native-Born American Terrorism

Native-born Americans have also committed terrorist attacks on U.S. soil and I investigated these cases for the 1975–2017 period.11 During that shorter time, I identified 192 foreign-born terrorists who murdered 3,037 people in attacks on U.S. soil and 788 native-born terrorists who murdered 413 people in attacks. Of the attacks where the terrorists’ nativity was known, 80 percent of the attackers were native-born, and 88 percent of the victims were murdered by foreign-born terrorists. During the post‑9/11 period through the end of 2017, native-born terrorists murdered 149 people in attacks, and foreign-born terrorists murdered 41. My research did not cover native-born American terrorists during later periods because complex methodological problems emerged, the time cost was prohibitive, and there was virtually no interest in these findings.12

Recent Terrorist Scares in the Interior of the United States

Two Jordanian individuals were arrested at the Marine Corps Base Quantico on May 3, 2024. According to the police incident report, they attempted to enter at a 100 percent identification checkpoint while driving a delivery truck en route to the Quantico post office. Guards stopped the truck, and the drivers handed over a delivery itinerary, a Virginia operator’s license, and a Jordanian passport. The guards asked if the drivers had base access and they replied that they did not. The guards instructed the drivers to drive toward a vehicle inspection and visitor check areas. However, the truck was not stopping, so the guards activated the final denial barriers, and the vehicle stopped before the barrier. The two Jordanians were arrested for trespassing and one of them was initially flagged on a terrorist watchlist, but that was an erroneous match.13 There is no material or other evidence indicating a terrorist plot and the police incident report did not mention any ramming attack. Thus, the trespassing case in Quantico, Virginia, is not evidence of terrorism.14

Eight Tajik men who crossed the U.S.-Mexico border in 2023 and 2024 were arrested in early June 2024 on immigration charges after the government learned they may have had contacts with ISIS or contacts with people who had potential ties to ISIS.15 There was no evidence to suggest that a specific targeted attack was planned, no evidence of an imminent threat to the homeland, and there have been no terrorism charges filed against them.16

The ongoing war between Israel and Hamas has raised terrorism concerns in the United States. Canadian police arrested Pakistani citizen and Canadian resident Muhammad Shahzeb Khan in September in connection with a complaint filed in the Southern District of New York.17 The complaint alleged that he was planning a mass shooting, which was uncovered after Khan began communicating with two undercover officers online about his plot. Khan is only charged with attempting to supply material support and resources to a foreign terrorist organization. In March 2024, Lebanon-born Basel Bassel Ebbadi was arrested by Border Patrol crossing the U.S.-Mexico frontier and almost immediately said, “I’m going to try to make a bomb,” and shortly thereafter said he had been trying to flee Lebanon and Hezbollah because he “didn’t want to kill people” and “once you’re in, you can never get out.”18 Ebbadi will soon be deported without terrorism charges.

There are cases of similar apprehensions. Border Patrol should continue to be on the lookout and CBP should continue to improve its screening and vetting capabilities.19 However, it’s important to note that the border security challenges faced by Israel and the United States are incomparable.20 Most relevant here is that no terrorists have ever illegally crossed the U.S.-Mexico border and committed an attack on U.S. soil while approximately 3,000 crossed Israel’s border last October and murdered more than 1,200 Israelis.21

Terrorism Screening Dataset Encounters on the Southwest Border

Customs and Border Protection (CBP) publishes statistics on the number of encounters of non‑U.S. citizens encountered by Border Patrol between ports of entry (POE).22 People encountered by Border Patrol are screened through the Terrorism Screening Dataset (TSDS).i CBP updates the number of positive hits frequently as part of its data releases. Although the published data only go back to 2017, there is a long-term increase in the number of non‑U.S. citizens encountered by Border Patrol who return positive hits in the TSDS, rising from 2 in 2017 to 100 through the end of August 2024 (Table 2).

Table 2: Border Patrol Terrorism Screening Dataset Encounters, 2017–2024YTD

Fiscal Year | Southwest Border (SWB) | Northern Border | Total | Border Patrol Encounters, SWB |

2017 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

303,916 |

2018 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

396,579 |

2019 |

0 |

3 |

3 |

851,508 |

2020 |

3 |

0 |

3 |

458,088 |

2021 |

15 |

1 |

16 |

1,734,686 |

2022 |

98 |

0 |

98 |

2,378,944 |

2023 |

169 |

3 |

172 |

2,063,692 |

2024YTD |

100 |

2 |

102 |

1,293,375 |

Source: Customs and Border Protection as of August 2024.

There are several reasons why these data do not indicate a threat of increased terrorist attacks on U.S. soil. First, the data quality is suspect and includes many false positives. For instance, the Texas Department of Public Safety (DPS) arrested a 29-year-old Iranian national named Alireza Heidari at a traffic stop in Val Verde County, Texas, in late 2022 or early 2023 as he was being smuggled with other illegal immigrants.23 DPS handed Heidari over to Border Patrol, who then initially identified Heidari as a match for somebody on the TSDS, which the media reported as such.24 After further data analysis, DHS announced that Heidari was not a match and was a false positive.25 It is unclear whether Heidari’s false positive was reported in CBP’s published statistics on TSDS hits. Errors such as “[f]alse positives are an inevitable consequence of any screening program,” and have been known to exist in the TSDS, although there is not much recent research on this issue.26 Most government investigations of errors in the TSDS are primarily concerned with reducing false negatives and they pay less attention to reducing false positives.27

Second, few people in the TSDS are terrorists. TSDS includes known and suspected terrorists (KSTs), which is a group of people less dangerous than it sounds. According to the FBI, a known terrorist is “an individual whom the U.S. Government knows is engaged, has been engaged, or who intends to engage in terrorism and/or terrorist activity, including an individual (a) who has been charged, arrested, indicted, or convicted for a crime related to terrorism by U.S. Government or foreign government authorities; or (b) identified as a terrorist or member of a designated foreign terrorist organization pursuant to statute, Executive Order or international legal obligation pursuant to a United Nations Security Council Resolution.”28 A suspected terrorist is “an individual who is reasonably suspected to be, or has been, engaged in conduct constituting, in preparation for, in aid of, or related to terrorism and/or terrorist activities based on an articulable and reasonable suspicion [emphasis added].”29

The inclusion of individuals in the TSDS who have undertaken actions that are “related to terrorism and/or terrorist activities” leads to more people being added to the TSDS than is likely warranted. After all, “related to” is open ended and causes vague talk of “ties” or “links” between people being mistaken for actual evidence of terrorism. Even worse, the process of adding an individual to the TSDS inflates the numbers. Originators at federal agencies nominate individuals for inclusion as KSTs in the TSDS. Next, analysts at the National Counter Terrorism Center (NCTC) or the FBI vet the nominees. NCTC has access to another database known as the Terrorist Identities Datamart Environment (TIDE) which is the government’s “central repository of information on international terrorist identities.”30 Not all identities in TIDE are included in the TSDS. To make it into the TSDS, a nomination vetted by the NCTC or FBI must 1) meet the “reasonable suspicion watchlisting standard” and 2) have sufficient identifiers to distinguish between individuals. Those sufficient identifiers must include at least one piece of biographic information like a first name or birthdate.31 The Terrorism Screening Center (TSC) verifies whether the person should be included under some circumstances.

A recent overview of the government’s terrorist watchlisting process and procedures defined the reasonable suspicion standard as:

The reasonable suspicion standard has been met when, based on the totality of the circumstances, there is reasonable suspicion that the person is engaged, has been engaged, or intends to engage in conduct constituting, in preparation for, or in aid or in furtherance of terrorism and/or terrorist activities. This includes taking into consideration any aggravating or mitigating factors that may contextualize or attenuate an individual’s association to terrorism.32

The reasonable suspicion standard and its exceptions are well summed up by the Congressional Research Service:

Articulable facts form the building blocks of the reasonable suspicion standard undergirding the nomination of suspected terrorists. Sometimes the facts involved in identifying an individual as a possible terrorist are not enough on their own to develop a solid foundation for a nomination. In such cases, investigators and intelligence analysts make rational inferences regarding potential nominees. The TSC vets all nominations, and when it concludes that the facts, bound with rational inferences, hold together to form a reasonable determination that the person is suspected of having ties to terrorist activity, the person is included in the TSDB. In the nomination process, guesses or hunches alone are not supposed to lead to reasonable suspicion. Likewise, one is not supposed to be designated a known or suspected terrorist based solely on activity protected by the First Amendment or race, ethnicity, national origin, and religious affiliation.33

Christopher Piehota, the former director of the TSC, testified that individuals can be included in the TSDS without a reasonable suspicion. He said, “There are limited exceptions to the reasonable suspicion requirement, which exist to support immigration and border screening by the Department of State and Department of Homeland Security.”34 In other words, the TSDS includes individuals who did not meet even this flimsy reasonable suspicion standard. Of the 1,558,710 nominations to the TSDS from FY2009-FY2013, 14,183 (0.9 percent) were rejected.35 As of February 2017, TIDE contained about 1.6 million people and 99 percent were neither U.S. citizens nor permanent residents.36 From 2011 to 2017, NCTC deleted about 228,000 people from TIDE.37 The government’s April 2024 overview of terrorist wathchlist process and procedures confirms this lower standard for immigration enforcement.38

Third, many individuals who are in the TSDS are not affiliated with foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs) that pose a threat to the U.S. homeland. CBP does not disclose the nationalities of immigrants who were a match for the terror watchlist. However, data released to the Washington Examiner showed that 25 of the 27 KSTs arrested by Border Patrol in the first six months of 2022 were citizens of Colombia and likely members or former members of FARC (which was delisted as an FTO in 2021), Segunda Marquetalia, the United Self Defense Forces of Colombia (delisted as an FTO in 2021), or the National Liberation Army.39 For instance, Border Patrol apprehended Isnardo Garcia-Amado in Arizona in early 2022 and released him into the country on April 18, 2022.40 Three days later, Garcia-Amado was flagged by the TSC as a positive hit on the TSDS. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrested him on May 6, 2022.41 There is no indication that he intended or was involved in any terrorism.

There has never been a terrorist attack committed on U.S. soil by Colombian groups, there is no evidence that they have ever intended to target the U.S. homeland, and no foreign-born person from Colombia has ever committed, planned, attempted, or been convicted of attempting to commit terrorism on U.S. soil.

Fourth, prosecutors have not filed terrorism charges against anyone who entered between a POE and who was flagged by the TSDS. There have been no attacks committed or thwarted by an individual who was flagged by the TSDS and entered between a POE. That’s evidence of an overinclusive watchlist, a small terrorist threat, effective law enforcement, excellent deterrence, all four factors in combination, or others.

Special Interest Aliens

DHS defines special interest aliens (SIA) as:

[A] non‑U.S. person who, based on an analysis of travel patterns, potentially poses a national security risk to the United States or its interests. Often such individuals or groups are employing travel patterns known or evaluated to possibly have a nexus to terrorism. DHS analysis includes an examination of travel patterns, points of origin, and/or travel segments that are tied to current assessments of national and international threat environments.42

According to a recent Daily Caller News Foundation article, Border Patrol agents encountered 25,627 SIAs in FY2022, with 60 percent of them coming from Turkey.43 Every Turk encountered by Border Patrol in FY2022 was counted as an SIA if the Daily Caller report is to be believed—all 15,356 encountered along the U.S.-Mexico border or all 15,360 of them encountered nationwide. It is likely that every illegal border crosser from Uzbekistan, Bangladesh, Syria, Iraq, and perhaps other countries was counted as an SIA.44

Another Daily Caller article claimed that CBP flagged 74,904 illegal migrants nationwide for potentially posing risks to national security between October 2022 and August.45 That is almost the same number of illegal immigrants who are from specifically listed countries outside of the Western Hemisphere who were encountered nationwide by Border Patrol (75,549).46 The difference is likely a result of a rounding error by Daily Caller’s source or the reporter.

In practice, the SIA definition corresponds to illegal immigrants from specific countries of origin.47 In other words, the SIA designation is a fancy label for “illegal immigration from a country that could have terrorists” and nothing more. The SIA designation is not the result of serious analysis, an understanding of individual behavior being correlated with terrorist activity, or anything deeper. As a result, SIA is not a metric that should seriously be considered when analyzing terrorist threats along the border.

As DHS makes clear:

This does not mean that all SIAs are “terrorists,” but rather that the travel and behavior of such individuals indicates a possible nexus to nefarious activity (including terrorism) and, at a minimum, provides indicators that necessitate heightened screening and further investigation. The term SIA does not indicate any specific derogatory information about the individual – and DHS has never indicated that the SIA designation means more than that.48

No SIA apprehended by Border Patrol has committed an attack on U.S. soil, which means that nobody has been killed or wounded by an SIA terrorist.

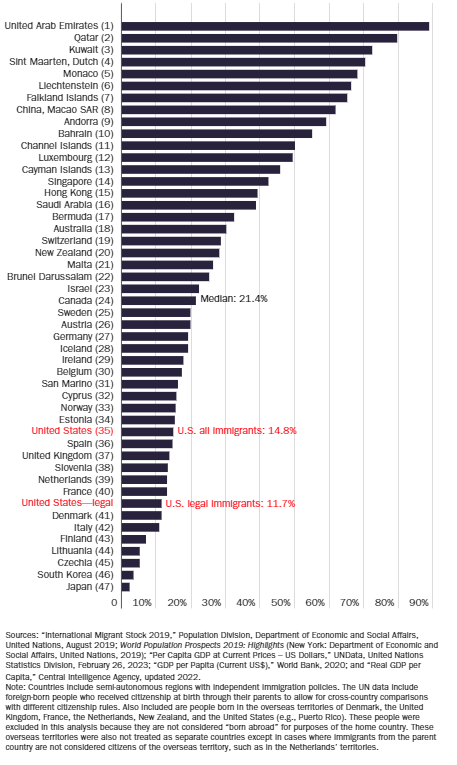

Reducing Illegal Immigration and Border Chaos

The chaos caused by illegal immigration is still a problem along the U.S.-Mexico border even if the terrorist threat is miniscule. The solution is to expand legal immigration for workers at every skill level for families, refugees, lawful permanent residents, temporary migrants, and other categories. The United States has a very restrictive legal immigration system.49 Compared to other developed countries, the foreign-born share of the U.S. population is 35th out of 47 (Table 3). The United States is in 40th place only counting legal admissions. The median foreign-born share of the population in rich countries is over 21 percent, but just 15 percent here. By increasing lawful immigration, the U.S. government would drive would-be illegal immigrants into the legal market. A shrunken black market would allow Border Patrol and other law enforcement agencies to focus on actual problems rather than trying to interrupt market forces. Furthermore, more legal immigration would allow the government to regulate and control the flow of immigrants to the United States. Congress can’t regulate an illegal market; it can only regulate a legal one.

We know expanding legal immigration works because of recent experiences with parole. The parole program Uniting for Ukraine, which was implemented in May 2022, reduced the total number of Ukrainians coming to the U.S.-Mexico border by 99.9 percent from April 2022 to July 2023. Almost the entirety of that collapse occurred in May 2022, the first month of the program. Similar parole programs for migrants fleeing Venezuela, Cuba, Nicaragua, and Haiti also reduced illegal entries. Venezuelan illegal entries fell 66 percent from September 2022 to July 2023. From December 2022 to July 2023, illegal entries from Haitians fell 77 percent, 98 percent from Cubans, and 99 percent from Nicaraguans.50 Parole is a great short-term stop-gap measure. Immigration liberalization is the only sustainable long-term fix to border chaos and illegal immigration.

Table 3: Immigrant Stock by Destination Country

Conclusion

Terrorism poses a risk to Americans’ lives, liberty, and private property. However, there is very little evidence that foreign-born terrorists have crossed or are crossing the U.S.-Mexico border. The evidence that terrorists are crossing the border is of such low quality that we can safely discount much of it. This fact could always change, and the future is unknowable, but available information indicates that foreign-born terrorists seeking to cross the U.S.-Mexico border is at most a very small and manageable threat. The scale of this small threat becomes especially obvious when compared to the myriad threats that face the United States internationally and domestically, or even the threat of normal homicide. The chaos along the U.S.-Mexico border is a travesty, but it will only be solved by expanding legal permanent immigration and temporary migration opportunities for families, humanitarian immigrants, and workers of every skill level. Only then will the flow of illegal border crossers diminish and allow Border Patrol to get control over the border, which will further reduce the already small chance of terrorists trying to cross the U.S.-Mexico border.

Appendix

Those 230 foreign-born terrorists include those who committed attacks on U.S. soil, those who planned or conspired to commit attacks and were thwarted by law enforcement before carrying out their attacks, those who committed violent crimes domestically to fund terrorism even if they never committed the actual terrorist attack or planned to do so, and threatened attacks if they made an actual effort to commit an attack, had bombmaking experience, or if they made it appear as if they committed the attack through a hoax.51 Their immigration status is determined by their initial immigration status when they first arrived on U.S. soil, a choice necessary because immigrants and migrants often adjust their statuses multiple times after arrival. I made this methodological choice because their initial immigration status is the first and most important point of potential security failure that could expose Americans to harm. For example, Faisal Shahzad is counted in my data as on a student visa because he initially entered on that visa and then obtained an H‑1B visa before his unsuccessful attempt at setting off a car bomb in Times Square in 2010.

The only exception to my methodological rule is for those seeking asylum in the United States—they are counted under the asylum visa if they applied for asylum shortly after entering the United States. That exception is important because those individuals usually make their asylum claim at the U.S. border or after they have entered on another visa, often with the intention of applying for asylum.

The number of murders and injuries committed by foreign-born terrorists includes those murdered or injured in the attacks, those who died afterward because of their injuries, and those accidentally killed or injured by police or security forces responding directly to the terrorist attack. The terrorists who died or who were injured in the attacks are not included as victims. If a foreign-born terrorist commits an attack with the aid of a native-born American, the foreign-born terrorist is credited with all the deaths and injuries committed in the attack. If multiple foreign-born terrorists commit an attack, I divide all the deaths and injuries equally among the foreign-born terrorists. Data on the identities of those terrorists, their visa status upon entry, countries or origin, ideology, the number of their victims, and other information comes from many different data sources.52

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.