President Obama’s 2008 campaign helped light a fire under the government transparency movement that still burns. However, the effort to produce transparent government has flagged. This is essentially because of poor awareness of exactly what practices produce transparent government.

Confusion between “open government” and “open government data” illustrates this. They are often treated as interchangeable, but the first is about revealing the deliberations, management, and results of government, and the second is general availability of data that the government has produced, covering any subject matter.

More importantly, the transparency community has failed to articulate what it wants. A quartet of data practices would foster government transparency: authoritative sourcing, availability, machine-discoverability, and machine-readability. The quality of government data publication by these measures is low.

We are not waiting for the government to produce good data. At the Cato Institute, we have begun producing data ourselves, starting with legislation that we are marking up with enhanced, more revealing XML code.

Our efforts are hampered by the unavailability of fundamental building blocks of transparency, such as unique identifiers for all the organizational units of the federal government. There is today no machine-readable organization chart for the federal government.

Well-published data, such as what the DATA Act requires, would allow the transparency community to propagate information about the government in widely varying forms to a public that very much wants to understand what happens in Washington, D.C.

Chairman Issa, Ranking Member Cummings, and members of the committee:

Thank you for the opportunity to testify before you today. I am keenly interested in the subject matter of your hearing, and I hope that my testimony will shed some light on your oversight of federal government transparency and assist you in your deliberations on how to promote this widely agreed-upon goal.

My name is Jim Harper, and I am director of information policy studies at the Cato Institute. Cato is a non-profit research foundation dedicated to preserving the traditional American principles of limited government, individual liberty, free markets, and peace. In my role there, I study the unique problems in adapting law and policy to the information age, issues such as privacy, intellectual property, telecommunications, cybersecurity, counterterrorism, and government transparency.

For more than four years, I have been researching, writing on, and promoting government transparency at Cato. For more than a dozen years, I have labored to provide transparency directly through a Web site I run called

WashingtonWatch.com. Other transparency related work of mine includes serving on the Board of Directors of the National Priorities Project, serving on the Board of Advisors of the Data Transparency Coalition, and serving on the Advisory Committee on Transparency, a project of the Sunlight Foundation run by my co-panelist today Daniel Schuman. WashingtonWatch.com is still quite rudimentary and poorly trafficked compared to sites like Govtrack.us, OpenCongress, and many others, but collectively the community of private, non-profit and for-profit sites have more traffic and almost certainly provide more information to the public about the legislative process than the THOMAS Web site operated by the Library of Congress and other government sites.

There is nothing discreditable about THOMAS, of course, and we appreciate and eagerly anticipate the improvements forthcoming on Congress.gov. But the many actors and interests in the American public will be best served by looking at the federal government through many lenses—more and different lenses than any of us can anticipate or predict. Thus, I recommend that you focus your transparency efforts not on Web sites or other projects that interpret government data for the public. Rather, your task should be to make data about the government’s deliberations, management, and results available in the structures and formats that facilitate experimentation. There are dozens—maybe hundreds—of ways the public might examine the federal government’s manifold activities.

Delivering good data to the public is no simple task, but the barriers are institutional and not technical. Your leadership, if well-focused, can produce genuine progress.

I will try to illustrate how to think about transparency by sharing a short recent history of transparency, a few reasons why the transparency effort has flagged, the publication practices that will foster transparency, our work at the Cato Institute to show the way, the need for a machine-readable government organization chart, and finally the salutary results that the DATA Act could have for transparency.

A Short Recent History of Federal Government Transparency

President Obama deserves credit for lighting a fire under the government transparency movement in his first campaign and in the first half of his first term. To roars of approval in 2008, he sought the presidency making various promises that cluster around more open, accessible government. Within minutes of his taking office on January 20, 2009, the Whitehouse.gov website declared: “President Obama has committed to making his administration the most open and transparent in history.“1 And his first presidential memorandum, entitled “Transparency and Open Government,” touted transparency, public participation, and collaboration as hallmarks of his forthcoming presidential administration.2

In retrospect, the prediction of unparalleled transparency was incautiously optimistic. But at the time, the Obama campaign and the administration’s early actions sent strong signals that energized many communities interested in greater government transparency.

My own case illustrates. In December 2009, between the time of President Obama’s election and his inauguration, I hosted a policy forum at Cato entitled: “Just Give Us the Data! Prospects for Putting Government Information to Revolutionary New Uses.“3 Along with beginning to explore how transparency could be implemented, the choice of panelists at the event was meant to signal that agreement on transparency would cross ideologies and parties, regardless of differences over substantive policies. That agreement has held.

In May 2009, White House officials announced on the new Open Government Initiative blog that they would elicit the public’s input into the formulation of its transparency policies.4 The public was invited to join in with the brainstorming, discussion, and drafting of the government’s policies.

The conspicuously transparent, participatory, and collaborative process contributed to an “Open Government Directive,” issued in December 2009 by Office of Management and Budget head Peter Orszag.5 Its clear focus was to give the public access to data. The directive ordered agencies to publish within 45 days at least three previously unavailable “high-value data sets” online in an open format and to register them with the federal government’s data portal, data.gov. Each agency was to create an “Open Government Webpage” as a gateway to agency activities related to the Open Government Directive.

They did so with greater or lesser alacrity.

But while pan-ideological agreement about transparency has held up well, the effort to produce transparent government has flagged. The data.gov effort did not produce great strides in government transparency or public engagement. And many of President Obama’s transparency promises went by the wayside.

His guarantee that health care legislation would be negotiated “around a big table” and televised on C‑SPAN was quite nearly the opposite of what occurred.6 His promise to post all bills sent him by Congress online for five days was nearly ignored in the first year.7 His promise to put tax breaks online in an easily searchable format was not fulfilled. Various other programs and projects have not produced the hoped-for transparency, public participation, and collaboration. And the Special Counsel to the President for Ethics and Government Reform, who handled the White House’s transparency portfolio, decamped for an ambassadorial post in Eastern Europe at the midpoint of President Obama’s first term.

It’s easy (and cheap) for critics of the president to chalk his transparency failures up to campaign disingenuousness or political calculation. It is true that the Obama administration has not shone as brightly on transparency as the president promised it would. But my belief is that transparency did not materialize in President Obama’s first term because nobody knew what exactly produces transparent government. The transparency community had not put forward clearly enough what it wanted from the government, and the transparency effort got sidetracked in a subtle but important way from “open government” to “open government data.”

Open Government vs. Open Government Data

When the White House instructed agencies to produce data for data.gov, it gave them a very broad instruction: produce three “high-value data sets” per agency. According to the open government memorandum:

High-value information is information that can be used to increase agency accountability and responsiveness; improve public knowledge of the agency and its operations; further the core mission of the agency; create economic opportunity; or respond to need and demand as identified through public consultation.8

That’s a very broad definition. Without more restraint than that, public choice economics predicts that the agencies will choose the data feeds with the greatest likelihood of increasing their discretionary budgets or the least likelihood of shrinking them. That’s data that “further[s] the core mission of the agency” and not data that “increase[s] agency accountability and responsiveness.”

“It’s the Ag Department’s calorie counts,” as I wrote before the release of data.gov data sets, “not the Ag Department’s check register.“9 And indeed that’s what the agencies produced.

In a grading of the data sets, I found that most failed to expose the deliberations, management, and results of the agencies. Instead, they provided data about the things they did or oversaw. The Agriculture Department produced data feeds about the race, ethnicity, and gender of farm operators; feed grains, “foreign coarse grains,” hay, and related commodities; and the nutrients in over 7,500 food items.

“That’s plenty to chew on,” I wrote in my review of all agency data sets, “but none of it fits our definition of high-value.“10

The agencies, and the transparency project, were diverting from open government to open government data. David Robinson and Harlan Yu identified this shift in policy focus in their paper: “The New Ambiguity of ‘Open Government.’ ” They wrote:

Recent public policies have stretched the label “open government” to reach any public sector use of [open] technologies. Thus, “open government data” might refer to data that makes the government as a whole more open (that is, more transparent), but might equally well refer to politically neutral public sector disclosures that are easy to reuse, but that may have nothing to do with public accountability.11

There’s nothing wrong with open government data, but the heart of the government transparency effort is getting information about the functioning of government. I think in terms of a subject-matter trio that I have mentioned once or twice already—deliberations, management, and results.

Data about these things are what will make for a more open, more transparent government. That is what President Obama campaigned on in 2008, it is what I believe you are interested in producing through your efforts, and it is what I believe will satisfy the American public’s demand for transparency. Everything else, while entirely welcome, is just open government data.

Publication Practices for Transparent Government

Deliberations, management, and results are complex processes, so it is important to be aware of another, more technical level on which the transparency project got bogged down. The transparency community did not meet public demand for, and political offer of, government transparency with a clear articulation of what produces it. We failed to communicate our desire for well-published, well-organized data, making clear also what that is.

Believing this to be the problem, I embarked in 2010 on a mission to learn what data publication practices will produce government transparency. A surprisingly intense, at times philosophical, series of discussions with propeller-heads of various types— information scientists, librarians, data geeks, and so on—allowed me to meld their way of seeing the world with what I knew of public policy processes.

In the Cato report, “Publication Practices for Transparent Government” (attached to my testimony as Appendix I), I sought to capture four categories of data practice that can produce transparency: authoritative sourcing, availability, machine-discoverability, and machine-readability. I summarized them briefly as follows:

The first, authoritative sourcing, means producing data as near to its origination as possible—and promptly—so that the public uniformly comes to rely on the best sources of data. The second, availability, is another set of practices that ensure consistency and confidence in data.

The third transparent data practice, machine-discoverability, occurs when information is arranged so that a computer can discover the data and follow linkages among it. Machine-discoverability is produced when data is presented consistent with a host of customs about how data is identified and referenced, the naming of documents and files, the protocols for communicating data, and the organization of data within files.

The fourth transparent data practice, machine-readability, is the heart of transparency, because it allows the many meanings of data to be discovered. Machine-readable data is logically structured so that computers can automatically generate the myriad stories that the data has to tell and put it to the hundreds of uses the public would make of it in government oversight.12

Following these data practices does not produce instant transparency. Users of data throughout the society would have to learn to rely on governmental data sources. Transparency, I wrote,

turns on the capacity of the society to interact with the data and make use of it. American society will take some time to make use of more transparent data once better practices are in place. There are already thriving communities of researchers, journalists, and software developers using unofficial repositories of government data. If they can do good work with incomplete and imperfect data, they will do even better work with rich, complete data issued promptly by authoritative sources.13

Our efforts have not ceased with describing how the government can publish data to foster transparency. Starting in January 2011, the Cato Institute began working with a wide variety of groups and advisers to "model" governmental processes as data and then to prescribe how this data should be published.

Our November 2012 report, "Grading the Government's Data Publication Practices"14 (part of which is attached to my testimony as Appendix II) examined how well the government publishes data reflecting legislative process and the budgeting, appropriating, and spending processes. Having broken down each element of these processes, we polled the community of government data users to determine how well that data is produced, and we issued letter grades.

The grades were generally poor, and my assessment (mine alone, not endorsed by other participants in our process) was that the House has taken a slight lead on government transparency, showing good progress with the small part of government it directly controls. The Obama administration, having made extravagant promises, lags the House by comparison. Since the release of the report, more signs of progress have come from the House, including forthcoming publication of committee votes, for example.15 This gap could easily be closed, however, if the administration gives focused attention to data transparency.

We Are Extending and Enriching Government Data Publication

Having assessed the publication practices that we believe will foster transparency, and having graded the government's publication practices in key areas, we are not waiting for good data to materialize. We have begun producing the data ourselves.

The low-hanging fruit for government transparency is the legislative process. In Congress, the long existence of the THOMAS Web site and the practice of publishing bills in a data format called XML (eXtensible Markup Language) make it easier to track what is happening than it is in other areas. But it is not easy enough, and we are working to make it even easier.

At the Cato Institute, we have acquired and modified software that allows us to extend the XML markup in existing bills. While most of the code embedded in the bills that Congress produces deals with the appearance of the bills when printed, we are adding code that fleshes out what the bills mean.

Using the data modeling we have done, we are tagging references to existing law in an organized, machine-readable way, so that people can learn instantly when a provision of law they care about is the subject of a bill. We are tagging budget authorities—both authorizations of appropriations and appropriations themselves—so that proposals to expend taxpayer funds are instantly and automatically available to the public and to you in Congress.

This being Sunshine Week, we are holding sessions tomorrow and Friday to examine how our enhanced bill XML can be a tool for Wikipedians. People across the country go to Wikipedia for information, including information about public affairs, and we would like to see that they are met there by good information about prominent pieces of legislation and our laws.

We plan to take our experience with marking up bills to other types of government documents and other processes. But it is difficult work. In the bills you write, you in Congress refer to existing law in varied, sometimes anachronistic ways. The varying ways your bills denote budget authorities sometimes make it very hard to represent clearly how many dollars are being made available for how many years.

But one of the problems we really should not be having is identifying the organizational units of government referred to in bills. In addition to tagging existing law and proposed spending, we tag agencies, bureaus, and such. But we are essentially unable to tag entities below the agency and bureau level, and the tagging we are doing uses identifiers we cannot be sure are reliable.

We are doing what we can to make bills available for computer interpretation—and we should be able to do wonders when appropriation season comes around—but we are hindered by the lack of a machine-readable federal government organization chart. We need this basic government data, which is essential to transparency.

Needed: A Machine-Readable Federal Government

Organization Chart Data is a collection of abstract representations of things in the world. We use the number "3," for example, to reduce a quantity of things to an abstract, useful form—an item of data. Because clerks can use numbers to list the quantities of fruits and vegetables on hand using numbers like "3," for example, store managers can effectively carry out their purchasing, pricing, and selling instead of spending all of their time checking for themselves how much of everything there is. Data makes everything in life a little easier and more efficient for everyone

Legislative and budgetary processes are not a grocery store's produce department, of course. They are complex activities involving many actors, organizations, and steps. The Cato Institute's modeling of these processes reduced everything to "entities," each having various "properties." The entities and their properties describe the things in legislative and budgetary processes and the logical relationships among them, like members of Congress, the bills they introduce, hearings on the bills, amendments, votes, and so on.

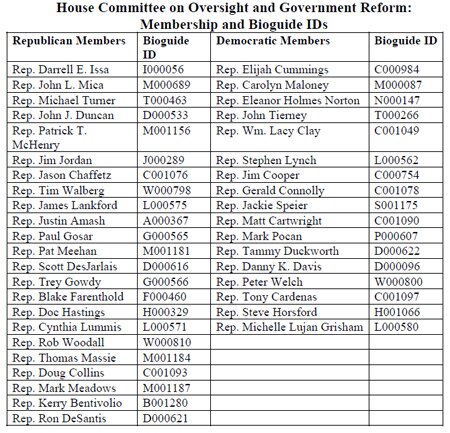

A member of Congress is an important entity in legislative process, as you might imagine. And happily, there are already systems in place to identify them accurately to computers. The "Biographical Directory of the United States Congress" is a compendium of information about all present and former members of the U.S. Congress (as well as the Continental Congress), including delegates and resident commissioners. The "Bioguide" website at bioguide.congress.gov is a great resource for searching out historical information about members.

Bioguide does a brilliant thing in particular for making the actions of Members of Congress machine-readable. It assigns a unique ID to each of the people in its database.

To illustrate how Bioguide works, I've copied the Bioguide IDs for each member of this committee into a table. The Bioguide IDs you see in this table are used across machinereadable documents and government Web sites to make crystal clear to computers exactly whom is being referred to when the name of a member of Congress is used, no matter what variation there is in the way the member is referred to in the resource.

This simple idea, of providing unique IDs for important components of governmental processes, is a basic building block of government transparency. Having Bioguide IDs has vastly improved the public's ability to oversee Congress, and the Congress's ability to track its own actions.

But unique identification has not been applied to many other parts of government. The most glaring example is the lack of authoritative and unique IDs for the organizational units of government. The agencies, bureaus, programs, and projects that make up the executive branch of government are not uniquely identified to the public in a similar way, and the relationships among all the federal government's organizational units is not authoritatively published anywhere.

In short, there is no machine-readable federal government organization chart. This is a glaring problem and a serious impediment to government transparency.

Were there a machine-readable federal government organization chart, the unique identifiers for organizational units could appear in all manner of document: budgets, authorization bills, appropriation bills, regulations, budget requests, and so on. Then we could use computing to help knit together stories about all the different agencies in our federal government, what they do, and how they use national resources. Internal management and congressional oversight would both strengthen. The DATA Act holds out the possibility of all this happening.

The DATA Act: That Organization Chart and More

The DATA Act essentially requires there to be a machine-readable government organization chart and much more. Building on widely lauded experience of the Recovery Accountability and Transparency Board, the DATA Act calls for data reporting standards that are "widely accepted, non-proprietary, searchable, platform-independent [and] computer-readable."16 This is the centerpiece of the DATA Act, from my perspective, and it is true of versions of the bill in both the House and the Senate last Congress.

To be a success, such standards must not only uniquely identify all the organizational units that carry out Congress's instructions in the executive branch. They must also identify budget documents; legislation; budget authorities; warrants, apportionments, and allocations; obligations; non-federal parties; and outlays.

Having unique identifiers for each of these things, and attributes that signal their relationships to one another, will allow vast stores of information to emerge from the data. "Seeing" the relationship between a given budget, a given appropriations bill, the obligation it funded, and an outlay of funds will make available the "story" of what Congress does year in and year out with taxpayers' money.

This data will make internal and congressional oversight far stronger. And it may help knit together the entire budget and spending process, so that expenditures can be matched to the results that Congress sought when it created programs and funded them. You in Congress and your constituents in the public will have better awareness of what happens in Washington, D.C. and in government offices around the country.

All this serves goals that span partisan and ideological lines. Organizing the spending process will reduce waste, fraud, and abuse in the first instance, as the likelihood of discovery will rise. Debates about programs may base themselves less on ideology and more on actual statistics about what spending achieved what results. In my "Publication Practices" paper, I wrote:

Transparency is likely to produce a virtuous cycle in which public oversight of government is easier, in which the public has better access to factual information, in which people have less need to rely on ideology, and in which artifice and spin have less effectiveness. The use of good data in some areas will draw demands for more good data in other areas, and many elements of governance and public debate will improve.17

I do believe this is true, though these ideal outcomes will not be reached automatically. Indeed, they will require a lot of effort to achieve.

Essential to producing the standards that foster these benefits is the existence of one authority positioned to require them. It seems natural for spending data standardization to be handled by the Office of Management and Budget, but that office has so far proven unwilling to move forward. Thus, the creation of a Federal Accountability and Spending Transparency board or commission may be warranted. My preference, of course, would be for economy in the creation of more federal entities to track…

I was surprised in September of 2011 to see the Congressional Budget Office estimate for the version of the DATA Act this committee reported to the House. The estimate of $575 million in outlays to implement the DATA Act over five years was quite nearly unbelievable. The thing that may make it believable is if waste, fraud, and abuse infects implementation of the DATA Act.

I believe that it will cost less than the CBO predicts to implement the DATA Act should it become law. Modifying federal data systems may have costs in the short term, but complying with standards should have essentially no cost after the initial retooling. If it does take as much to fully implement the Act as the CBO estimates, that is proof of a sort that we need oversight systems like this that can hold costs down.

The GRANT Act, FOIA Reform, and More

Our transparency research and work has not extended to federal grant-making, which is a significant subset of all federal spending. It seems obvious that bringing transparency and organizational rigor to grant administration would have similar salutary effects to what we can expect in government spending generally.

Outright waste would be curtailed. The results of grant-making for public policy goals would be clearer. And participants in the grant-making process would be more sure of fair treatment.

I understand there are concerns with the version of the GRANT Act introduced in the last Congress, such as with the potential that anonymous peer review might be undercut by transparency. This is a genuine issue, which can almost certainly be overcome with some careful thinking and planning. If it cannot, my belief is that the interest of the taxpayer in accountable grant administration is generally superior to the interests of peer reviewers in privacy or anonymity.

Of course, Freedom of Information Act reforms are an important part of the transparency agenda. I am not expert in FOIA, and it is my hope that proactive and thorough data transparency may partially diminish the need for FOIA requests because transparency policy has made clear what deliberative processes agencies have used, for example.

Even in a world with the fullest data transparency, there will be a public need for access to key government documents and information on request. I support the FOIA reforms that will get the most important information disseminated the most broadly so that American democracy functions better and so that public oversight of the government is strong.

Conclusion

It is a pleasure to work on an issue like transparency, widely supported as it is across partisan and ideological lines. Transparency is a means to various ends that can co-exist. I believe, for example, along with my conservative friends, that transparency will reduce the demand for government and increase the demand for private authority over decisions and spending that the government currently controls. If transparency produces this result, it will be a product of democratic processes that I think my liberal and progressive friends would be hard-pressed to reject. If, on the other hand, transparency wrings waste, fraud, and abuse out of government programs, validating them and increasing their support, I will enjoy the gain of having a better-managed government.

If there is division in the transparency issue, it is between the outsiders and the insiders. Information is power, and non-transparent practices are a way of preserving power for the few who have attained it.

The enjoyment of power by the few is inconsistent with the underlying theory of democracy, of course, and with our shared American commitment to the idea that power springs from the people. The moral high-ground in debates about transparency is always with those who want to know more about what their government is doing with their money and their rights. While there may be some narrow exceptions to the rule that the people have a right to know, the transparency status quo is far from that line.

Anything this committee can do to improve the quality and quantity of data about the government’s deliberations, management, and results will bring credit to the committee and this Congress.

Notes

1Macon Phillips, “Change Has Come to Whitehouse.gov,” The White House Blog, January 20, 2009 (12:01 p.m. EDT), http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/change_has_come_to_whitehouse-gov.

2 Barack Obama, “Transparency and Open Government,” Presidential Memorandum (January 21, 2012),http://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/transparency-and-open-govern….

3 Cato Institute, “Just Give Us the Data! Prospects for Putting Government Information to Revolutionary New Uses,” Policy Forum, December 10, 2008, https://www.cato.org/event.php?eventid=5475.

4 Jesse Lee, “Transparency and Open Government,” May 21, 2009,http://www.whitehouse.gov/blog/2009/05/21/transparency-and-open-governm….

5Peter R. Orszag, “Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies, Subject: Open Government Directive,” M 10–06, December 8, 2009, http://whitehouse.gov/open/documents/opengovernment-directive [hereinafter “Open Government Directive”].

6 “Negotiate Health Care Reform in Public Sessions Televised on C‑SPAN,” Politifact.com,http://www.politifact.com/truth-o-meter/promises/obameter/promise/517/h….

7 Jim Harper, “Sunlight Before Signing in Obama’s First Term,” Cato blog, February 12, 2013, https://www.cato.org/blog/sunlight-signing-obamas-first-term.

8 Open Government Directive.

9 Jim Harper, “Is Government Transparency Headed for a Detour?” Cato blog, January 15, 2010,https://www.cato.org/blog/government-transparency-headed-detour.

10 Jim Harper, “Grading Agencies’ High-Value Data Sets,” Cato blog, February 5, 2010,https://www.cato.org/blog/grading-agencies-high-value-data-sets.

11 Harlan Yu and David G. Robinson, “The New Ambiguity of ‘Open Government,’ ” UCLA Law Review 59, no. 6 (August 2012): 178.

12 Jim Harper, “Publication Practices for Transparent Government,” Cato Institute Briefing Paper no. 121,September 23, 2011, https://www.cato.org/publications/briefing-paper/publication-practices-… “Publication Practices”].

13 Id.

14 Jim Harper, “Grading the Government’s Data Publication Practices,” Cato Policy Analysis no. 711,November 5, 2012, https://www.cato.org/publications/policy-analysis/grading-governments‑d….

15 See Jim Harper, “Sunlight Before Signing in Obama’s First Term,” Cato blog, February 12, 2013,https://www.cato.org/blog/sunlight-signing-obamas-first-term.

16 H.R. 2146 (112 Cong., 2nd Sess.).

17 Publication Practices.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.