President Donald Trump and Republicans in Congress are considering major tax reforms. The House Republican tax plan would cut business and individual income tax rates, and make other reforms to reduce taxes on savings and investment.1

For individuals, the House plan suggests creating Universal Savings Accounts (USAs), based on legislation introduced by Sen. Jeff Flake (R‑AZ) and Rep. Dave Brat (R‑VA).2 The accounts would simplify and reduce taxes on personal savings, thus encouraging individuals to save more and build greater financial security.

Both the United Kingdom and Canada have created USA-style accounts. The accounts are popular, and a large share of people in every age and income group use them.

This bulletin discusses the taxation of savings, the British and Canadian reforms, and the opportunity to simplify the tax code and increase savings with USAs.

Tax Treatment of Personal Savings

Saving is a root source of economic growth because it provides businesses with the investment funds they need to expand and modernize. Saving also supports personal financial stability, allowing people to cover large or unplanned expenses in the short term while building a comfortable retirement in the long term.

However, broad-based income taxation penalizes saving compared with current consumption because the return to saving is taxed but consumption is not. Income taxes therefore encourage people to spend their earnings now, rather than save for future needs.

This anti-saving bias is widely recognized, and most countries with income taxes mitigate the problem with special rules for the returns to savings. Our federal tax code includes, for example, 401(k)s, Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs), and other vehicles designed to reduce taxes on retirement savings.

However, all savings are beneficial, not just retirement savings. Additional savings would allow families to cover health care, education, and other large and sometimesunexpected costs more easily. If Americans had larger pools of savings, they would be more self-sufficient and less in need of government aid programs.

As a complement to existing retirement savings provisions, the U.K. and Canada created vehicles designed to encourage all types of saving. These are called Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs) in the U.K. and Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs) in Canada.

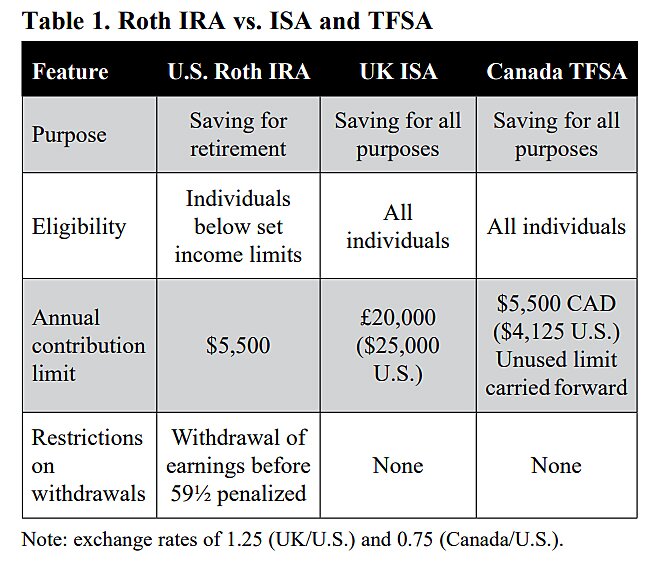

The tax treatment of ISAs and TFSAs is similar to that of American Roth IRAs. Individuals deposit after-tax earnings into the accounts, then earnings and qualified withdrawals are tax-free. However, the British and Canadian accounts are much more flexible than Roth IRAs and are far more popular, as discussed in the following sections. Table 1 shows the basic rules for the accounts.

British Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs)

The U.K. has taken large steps to reduce the tax bias against saving under its income tax. Dividends and capital gains benefit from reduced individual tax rates and substantial tax-free exemption amounts. The tax code also includes generous provisions for retirement saving. British pension taxation is similar to U.S. taxation of 401(k)s — contributions are deducted, then pension income is taxed when received in retirement. British pension saving is further favored with a tax exclusion on a one-time withdrawal of up to 25 percent of pension assets.3

The U.K. government has also created favorable rules for nonretirement savings. Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government introduced Personal Equity Plans in 1986 and Tax-Exempt Special Savings Accounts in 1990, both of which allowed for after-tax contributions to tax-free savings vehicles.

Tony Blair’s Labour government replaced those accounts in 1999 with Individual Savings Accounts (ISAs). The rules on these accounts have been liberalized over time, and 21.7 million people hold an ISA today, or 43 percent of all British adults.4

The tax treatment of ISAs is simple. Individuals contribute from after-tax earnings, but then pay no taxes on interest, dividends, or capital gains on the earnings. Savers can withdraw their funds at any time, for any reason, without any taxes or penalties. Savers can transfer their money between ISA fund managers easily. There are no income limits for ISA eligibility and no lifetime limits on deposits or tax-free earnings.

The annual contribution limit for ISAs is remarkably high. The government recently increased it to £20,000, or about $25,000.5 With this limit, ISAs have ended the tax penalty on savings for all but the highest earners in the U.K.

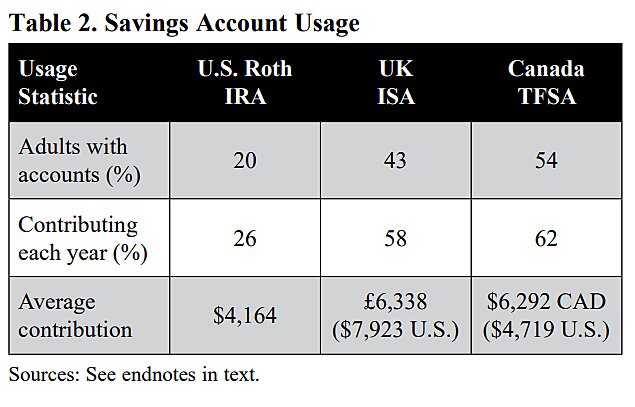

The liberal rules on ISAs have made them popular, as shown in Table 2.6 The ISA ownership rate of 43 percent of adults compares with about 20 percent for Roth IRAs.7 The ISA contribution rate is higher as well. About 58 percent of ISA owners contribute to their accounts each year, compared with just 26 percent of Roth IRA owners.8

Furthermore, the British contribute more to ISAs than Americans do to Roth IRAs. The average annual ISA contribution is about £6,338 ($7,923), which compares to the average for Roth IRAs of $4,164.9 The British experience with ISAs indicates that the public has a strong demand for a general-purpose tax-free savings account.

ISAs are popular with people at all income levels. About 55 percent of all ISA holders have incomes of less than £20,000 ($25,000).10 Relative to their incomes, lower earners hold more in their ISAs than higher earners. For example, the average account value for people earning between £10,000 and £19,999 was £19,538 in 2014, while the average for those earning more than £150,000 was £64,148.11

The popularity of ISAs is not surprising. The accounts are more liquid than retirement accounts because funds can be withdrawn at any time without taxes or penalties. Liquidity is important to people with moderate incomes because they are more likely than others to face short-term contingencies that strain their resources.

ISAs are a successful policy innovation, but the government has added unnecessary complexities. A single ISA would be sufficient, but the government created separate“cash” and“stocks and shares” ISAs as well as a separate“junior” ISA for those under age 18.

In 2015 the government added a“Help to Buy ISA,” which includes subsidies for home buying.12 In 2016, the government created a“Lifetime ISA” for people under age 40 with an annual contribution limit of £4,000. The government tops up Lifetime contributions with a 25 percent bonus, thus adding a subsidy of up to £1,000.13 Funds in Lifetime accounts can be withdrawn tax-free after age 60 or for a home purchase, but other withdrawals face a charge.14

The basic ISA is an excellent vehicle, but these other ISAs are misguided. Governments should strive to create neutral treatment of saving and consumption, but they should not subsidize saving or favor some types of saving over others.

In sum, both Labour and Conservative governments have recognized the importance of personal savings and supported the expansion of ISAs. The basic ISA has an annual contribution limit more than four times higher than the Roth IRA limit. Despite the unneeded complexity, ISAs have been a success — as evidenced by their widespread popularity.

Canadian Tax-Free Savings Accounts (TFSAs)

Like the U.K., Canada has taken major steps to reduce the tax bias against savings under its income tax. It imposes reduced tax rates on dividends and capital gains. It also has an employer-based pension system as well as a popular individual pension vehicle, the Registered Retirement Savings Plan (RRSP).15 The tax treatment of RRSPs is similar to that of U.S. 401(k)s.

The government added TFSAs in 2009 to encourage savings for all purposes, as a complement to RRSPs. The government envisioned a typical user in different phases of her life: saving for a car in her 20s, saving for a home in her 30s, saving for home renovations in her 40s, saving for her child’s wedding in her 50s, saving for a recreational vehicle in her 60s, and using the remaining account balance for retirement income.16

Individuals can deposit up to $5,500 after-tax each year into TFSAs. However, unused portions of the annual limits can be carried forward if not used. If you contribute $2,000 this year, you will be able to add $9,000 next year ($3,500 + $5,500). Beginning at age 18, all unused contribution amounts can be carried forward indefinitely and used later.

All TFSA earnings and withdrawals are tax-free, and withdrawals can be made at any time for any reason with no penalties. TFSAs have no income limits. All adults can contribute and withdraw at any time during their lives. TFSAs can be opened at any bank branch or online. They can hold bank deposits, stocks, bonds, mutual funds, and other types of assets.

TFSAs are hugely popular, with 54 percent of Canadian adults now owning them.17 That is a much higher ownership rate than the 20 percent for Roth IRAs — even though Roths have been around longer. In 2014, 62 percent of TFSA holders contributed to their accounts, compared with just 26 percent of Roth IRA holders.18

As with the British ISA, TFSAs are heavily used by moderate-income individuals. In 2014, 55 per cent of TFSA holders earned less than $50,000 Canadian ($37,500 U.S.).19

A spokesman for a major Canadian bank said,“The magic behind the TFSA is in its versatility. It is not simply a tax measure designed to help low-income Canadians, but rather a vehicle that can fit almost every Canadian, regardless of income or stage of life.”20

Taking advantage of the TFSA’s ease of use and universal nature, Canadian news media and financial institutions have extensively marketed the accounts, which has helped promote a culture of saving. An article in the Globe and Mail said,“TFSAs have already become a great Canadian institution. It’s simplicity that sells the TFSA.”21

Universal Savings Accounts (USAs)

Canadian- and British-style savings accounts may be coming to America. Sen. Jeff Flake (R‑AZ) and Rep. Dave Brat (R‑VA) have introduced companion bills — S. 323 and H.R. 937 — to create Universal Savings Accounts (USAs).22

Under the legislation, anyone 18 years of age or older could open a USA and contribute up to $5,500 in cash per year after-tax. Account holders could make withdrawals tax- and penalty-free at any time for any reason.

USA funds would be invested in bonds or equities, and would grow tax-free. USAs would allow individuals to decide what to use their savings for and when, without Congress micromanaging their choices, as it does with current tax-preferred savings accounts.

The Flake-Brat legislation proposes USAs as an additional vehicle alongside existing saving plans. However, a goal of current Republican tax reform efforts is simplification. As such, policymakers should consider replacing a number of savings vehicles with large USAs. We suggest creating USAs with an annual contribution limit of $10,000 or more, combined with the elimination of traditional IRAs, Roth IRAs, and Coverdell Education Savings Accounts (ESAs).23

Traditional IRAs generally allow a tax deduction for contributions and then taxation of withdrawals in retirement.24 The bulk of assets in traditional IRAs come from rollovers, mainly from 401(k)s.25 Roth IRAs allow for after-tax contributions and tax-free withdrawals during retirement. The combined annual contribution limit for IRAs is $5,500.26 ESAs have an annual contribution limit of $2,000 per child, tax treatment similar to Roth IRAs, and complex rules on withdrawals. All three types of accounts have income limits, penalties for nonqualified withdrawals, and myriad other rules.27

For savers, USAs are superior to these accounts because they are simpler and more flexible. USAs could be used for retirement, education, or saving for any other purpose.

The following sections discuss the advantages of creating large USAs.

Simplify Financial Planning. The federal government micromanages personal finances by favoring some types of saving over others. The result is a mess of separate vehicles for retirement, education, and other purposes. Financial planning would be simpler if people did not have to navigate the rules and restrictions related to numerous separate accounts.

Large USAs would reduce complexity because they would hold all savings other than employer-based retirement savings for many families. Owning a USA would be as simple as owning a bank account, which would encourage young people, people with moderate incomes, and others to save.

Promote Personal Savings. The overall U.S. personal saving rate was fairly high in the mid-20th century, but it has fallen substantially since the 1980s.28 That statistic and numerous surveys reveal that many Americans are not saving very much. A triennial Federal Reserve survey, for example, asks families whether they saved on net during the prior year, and only about half answer affirmatively.29

Many people have not accumulated adequate savings for short-term contingencies. A National Bureau of Economic Research study found that about half of Americans could not come up with $2,000 in 30 days other than by pawning possessions or taking out costly loans.30 One problem, the authors said, is that although retirement savings are tax-preferred,“income earned from emergency savings accounts receives no special treatment. To the contrary, asset limits on many social programs actively discourage low-income families from building up savings.”31

However, it is not just low-income families who are not saving. The study’s authors found that“a sizable fraction” of seemingly middle class people do not have adequate savings for short-term contingencies either.

Other surveys have similar results. An Employee Benefits Research Institute survey found that 47 percent of workers had less than $25,000 in overall savings and 24 percent had less than $1,000.32 A poll reported in USA Today found that 34 percent of adults had no money set aside for an emergency, while 47 percent said their savings would cover their living expenses for 90 days or less.33

There are likely many causes contributing to today’s often low levels of saving.34 Changes in demographics and consumer culture may have played a role, as well as the increased availability of debt financing for purchases.

Government policy has also had an effect. The expansion of the welfare state has reduced the perceived need for personal savings.35 Also, the income tax is biased against saving, as noted, and it encourages debt finance, as with the provision of the mortgage interest deduction.36

In pursuing tax reform, policymakers should aim for neutrality between saving and current consumption, while also removing the advantages that debt receives. USAs would modestly help right the balance. They might, for example, encourage more people to save for purchases, rather than maximizing debt financing.

Increased savings would improve the ability of people to deal with economic shocks, such as the loss of a job, health expenses, or the cost of a major car repair. Savings can also increase economic opportunity by providing funds to support further education or start a business.

Many people currently get funds to cover short-term expenses by withdrawing from, and borrowing from, their retirement accounts.37 A blue ribbon commission on personal savings reported last year,“Insufficient short-term savings can lead workers to draw down their retirement accounts, incurring taxes and (often) penalties. This ‘leakage’ of retirement savings … jeopardizes many Americans’ long-term retirement security.”38

Pension experts Alicia Munnell and Anthony Webb studied the leakage, and found that it reduced aggregate retirement wealth in 401(k)s and IRAs by more than 20 percent.39 The leakage happens within an array of complex rules on retirement accounts that govern which sorts of withdrawals are allowed and which are penalized.

Munnell and Webb would impose tougher rules to reduce leakage, but that approach would make retirement accounts less attractive. Leakage happens because people need their money now rather than later. A solution would be to create a savings vehicle with tax benefits similar to retirement accounts, but one that would allow withdrawals without a mess of rules, penalties, and paperwork.

That was part of the thinking behind TFSAs. A Canadian bank economist noted that TFSAs“can be accessed multiple times during one’s lifetime to serve as emergency funds, and to bridge periods of income volatility. This liquidity feature of the TFSA plan is of great importance as it will probably work to limit or even eliminate uneconomical behavior such as RRSP withdrawal.”40

Today, IRAs allow early withdrawals for hardship reasons, education expenses, first-time home purchases, and some medical expenses. But why should politicians be favoring some uses of our personal savings over others? Why not have an account that allows people to save and withdraw as they please?

As Munnell and Webb noted,“studies show that employees who know that they can get access to their funds are more likely to participate and to contribute more once they join the plan.”41 That is exactly right — and it is a big advantage of USAs. By providing maximum liquidity, USAs would encourage more people to save and contribute as much as they could to build their wealth.

Benefit People at All Income Levels. Use of USAs would likely be more equal across income groups than usage of current savings vehicles. Data for IRAs and ESAs show that use is tilted toward higher earners. For example, 26 percent of households with earnings of more than $50,000 have Roth IRAs, whereas just 7 percent of families earning less than $50,000 do.42

Of course, lower earners have a tougher time saving because their core expenses are high compared with their incomes. In addition, lower earners face lower income tax rates, so they are typically less interested in the tax-shielding benefits of savings vehicles.

However, another issue is that low- and middle-income earners avoid special-purpose savings accounts because of concerns about liquidity. A Congressional Research Service study described this issue with respect to ESAs:“the penalties for using educational savings for non-educational purposes may discourage lower-income families from having these accounts.”43 Since children from lower-income families are less likely to attend college than other children, the study notes, it is more risky for them to use ESAs, and so fewer do.

USAs would solve this problem. They would allow moderate-income families to save with no chance of being hit with penalties. Discussing similar accounts proposed in 2003, former chair of the Council of Economic Advisors Glenn Hubbard noted,“With no withdrawal penalties, the account’s greater liquidity will encourage individuals to save, particularly moderate-income households worried about tying up funds for a long period of time.”44

Indeed, the British and Canadian experiences show large participation by people of modest means. In the U.K., 55 percent of all ISA holders have incomes of less than £20,000 ($25,000).45 In Canada, 55 per cent of TFSA holders earn less than $50,000 (U.S. $37,500).46 The average TFSA holder earning $50,000 had an account worth $13,600 in 2014, while the average TFSA holder earning $100,000 had an account worth about $15,000.47 As in the U.K., lower earners in Canada save more in their accounts relative to income than do higher earners.

Benefit People of All Ages. The main savings vehicles in the U.S. tax code — defined-benefit pension plans, 401(k)s, and IRAs — encourage retirement savings. But to young people, retirement seems a long way off, and their financial goals are more likely to include saving for college, for a home, or for starting a business.

The Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances shows that“retirement” becomes the primary purpose people give for saving only for age groups 40 and over.48 Younger people give a range of other reasons, so USAs should be particularly attractive to them.

USAs would also fill a void with the elderly, since the tax code currently discourages their saving. Traditional IRAs and 401(k)s require minimum distributions after age 70½ and do not allow contributions. But why should frugal retirees be discouraged from saving? They should have the option of keeping funds invested without added taxes. Roth IRAs address this issue by allowing deposits at any age, and USA accounts would expand on that capability.

In the U.K., people of all ages use ISAs. In 2014, 21 percent of young adults (age 18–34) made new ISA contributions, as did 27 percent of people in middle age (age 35–64), and 27 percent of people of retirement age (65+).49

It is similar in Canada with TFSAs. In 2014, 23 percent of young adults, 24 percent of people in middle age, and 33 percent of people of retirement age made contributions.50

Complement Entitlement Reforms. In coming decades, spending on Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid is expected to soar. If these programs are not reformed, the growing costs will impose large burdens on future taxpayers. Policymakers should overhaul the programs to reduce costs and limit the economic damage.

In parallel, policymakers should pursue reforms to increase the self-sufficiency of Americans and reduce the overreliance on federal benefits. Reforms should include reducing barriers to personal savings with USAs so that individuals can cover more of their own costs for unemployment, retirement, and other life events.

Looked at another way, projections show that revenues will be insufficient to pay promised entitlement benefits. Social Security benefits, for example, are scheduled to be cut about 20 percent in the 2030s when the program’s trust fund is exhausted. Actually, benefits are likely to be cut before then as rising entitlement spending pushes up federal deficits to crisis levels.

Thus, it is prudent for young people to increase their savings so that they will be able to weather future entitlement cuts, and so that they will be better prepared for negative shocks such as recessions. Some people are more prudent planners than others, of course, but USAs would provide a modest nudge to all Americans to adopt a more frugal approach to their finances.

Conclusions

Current federal policies favor saving for some purposes over others. But all saving is beneficial because it improves personal financial security and provides funds for capital investment in the economy. USAs would reduce the tax bias against saving in an across-the-board manner for all individuals. The accounts would encourage people to save for future expenses rather than relying on debt and government aid.

British and Canadian experiences show that people of all ages and income levels would use a general-purpose savings vehicle. Those experiences also indicate that the financial industry would embrace and promote USAs, thus helping support a broader savings culture.

The Flake–Brat legislation to create USAs is on the right track. However, the annual contribution limit should be increased to $10,000 or more so that the accounts could cover all the nonretirement savings that most people need. We think that the tax, simplification, and liquidity benefits of USAs would generate their widespread use across the USA.

Notes:

1 House Republicans,“A Better Way: Our Vision for a Confident America,” June 2016, http://abetterway.speaker.gov.

2 The bills are S. 323 in the Senate and H.R. 937 in the House.

3 This framework benefits people whose marginal tax rate falls during retirement, which is often the case in a graduated tax system. The feature allows lifetime income smoothing. See Philip Booth and Ryan Bourne,“Pensions Tax Reform: A Briefing,” Institute of Economic Affairs, February 6, 2016.

4 HM Revenue and Customs, Individual Savings Account (ISA) Statistics (London: National Statistics, August 2016), p. 27. Data for 2013–14.

5 HM Treasury,“Tax and Tax Credit Rates and Thresholds for 2017–18,” November 23, 2016. We use a pound–dollar exchange rate of 1.25.

6 Table 2 data for the United States are from Investment Company Institute,“The Role of IRAs in U.S. Households’ Saving for Retirement, 2016,” ICI Research Perspective 23, no. 1 (January 2017); and Craig Copeland,“Individual Retirement Account Balances, Contributions, Withdrawals, and Asset Allocation Longitudinal Results 2010–2014,” Employee Benefits Research Institute Issue Brief no. 429, January 17, 2017. Data for the U.K. are from HM Revenue and Customs, Individual Savings Account (ISA) Statistics. Data for Canada are from Canada Revenue Agency,“Tax-Free Savings Account Statistics 2016 Edition (2014 Tax Year),” October 13, 2016; and Bank of Montreal,“BMO Annual TFSA Study,” February 23, 2017.

7 U.S. ownership for 2016, U.K. for 2013–14, and Canada for 2016. The Investment Company Institute reports that Roth IRAs were owned by 17.4 percent of U.S. households in 2016. We estimate that equals about 20 percent of U.S. adults based on ICI data on the share of IRA and non‐IRA holders who are married.

8 U.S. contribution rate for 2014, U.K. for 2013–14, and Canada for 2014. Note that only 7 percent of traditional IRA owners contribute each year, per data in Copeland.

9 U.S. average contribution for 2014, U.K. for 2015–16, and Canada for 2014.

10 HM Revenue and Customs, Individual Savings Account (ISA) Statistics, p. 25. Data for 2013–14.

11 Ibid.

12 HM Treasury,“Help to Buy: ISA. Scheme Outline,” March 2015.

13 HM Revenues and Customs,“What You Need to Know about the New Lifetime ISA,” February 17, 2017.

14 Some people want to integrate all ISAs into Lifetime ISAs and harness them for retirement saving. See Michael Johnson,“Introducing the Lifetime ISA,” Centre for Policy Studies, August 2014. But that would eliminate the flexibility of ISAs and would likely mean the end of the pensions tax relief system, which allows income smoothing for those with fluctuating incomes. See Booth and Bourne.

15 RRSPs can be either individual or group vehicles, with the latter offered through employers.

16 Government of Canada, Department of Finance,“The Budget Plan 2008: Responsible Leadership,” February 26, 2008, p. 79.

17 Bank of Montreal figure for 2016. The last government data were for 2014 and indicated 41 percent ownership. Thus, the bank figure may be high, although TFSA ownership has been increasing.

18 Canada figure for 2014. Canada Revenue Agency, Table 1.

19 Ibid., Table 1C. We use a Canada–U.S. exchange rate in this bulletin of 0.75.

20 CIBC,“New Tax‐Free Savings Accounts Will Jumpstart Canadian Savings Rate after Years of Decline,” News Release, September 11, 2008.

21 Rob Carrick,“How to Build a $1‑million TFSA,” Globe and Mail, April 17, 2016.

22 Chris Edwards and Ernest Christian proposed Universal Savings Accounts in a 2002 Cato Institute bulletin. The George W. Bush administration proposed similar Lifetime Savings Accounts in 2003.

23 There are numerous other tax‐preferred savings accounts, including SIMPLEs, SEPs, and 529 education plans. Congress should aim to consolidate as many vehicles as possible to simplify financial planning.

24 For traditional IRAs, the deductibility of contributions depends on a person’s income and access to an employer plan.

25 Investment Company Institute,“The Role of IRAs,” p. 14. See also Victoria L. Bryant and Jon Gober,“Accumulation and Distribution of Individual Retirement Arrangements 2010,” Internal Revenue Service, Statistics of Income Bulletin, Fall 2013.

26 The limit is $6,500 for people age 50 and over.

27 For ESAs and Roth IRAs, withdrawals of contributions can be made any time, but withdrawals of earnings may be subject to taxes and a penalty. For Roth withdrawals of earnings, individuals must generally be 59½ and accounts must have been held five years.

28 The personal savings rate bottomed out about a decade ago, but has a risen a bit since then. Measures of the personal savings rate from both the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Federal Reserve show a drop over the decades. However, those indicators have shortcomings. The Bureau figure does not include capital gains and the Fed figure does not include unrealized capital gains, so both miss a large share of personal wealth accumulation.

29 Jesse Bricker et al.,“Changes in U.S. Family Finances from 2010 to 2013: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances,” Federal Reserve Bulletin 100, no. 4 (September 2014), p. 13.

30 Annamaria Lusardi, Daniel J. Schneider, Peter Tufano,“Financially Fragile Households,” National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper no. 17072, May 2011.

31 Ibid.

32 Lisa Greenwald, Craig Copeland, and Jack VanDerhei,“The 2017 Retirement Confidence Survey,” Employee Benefit Research Institute, Issue Brief no. 431, March 21, 2017, p. 12. Does not include the value of homes or defined benefit pension plans.

33 Charisse Jones,“Millions of Americans Have Little to No Money Saved,” USA Today, March 31, 2015.

34 Factors affecting the savings rate are explored in Thomas L. Hungerford,“Savings Incentives: What May Work, What May Not,” Congressional Research Service, June 20, 2006.

35 Solid evidence suggests, for example, that individuals reduce their private retirement savings when government retirement benefits increase. See Andrew G. Biggs,“An Agenda for Retirement Security,” National Affairs 31 (Spring 2017): 21–40.

36 With regard to income taxes, empirical studies looking at the relationship between savings vehicles and savings rates have generated a wide range of results. For a summary, see Bradley T. Heim and Ithai Z. Lurie,“The Effect of Recent Tax Changes on Tax‐Preferred Saving Behavior,” National Tax Journal, June 2012.

37 About one‐fifth of eligible 401(k) holders have had a loan outstanding in recent years.

38 Bipartisan Policy Center,“Securing Our Financial Future: Report of the Commission on Retirement Security and Personal Savings,” June 2016.

39 Alicia H. Munnell and Anthony Webb,“The Impact of Leakages from 401(k)s and IRAs,” Center for Retirement Research at Boston College, Working Paper no. 2015–2, February 2015. See also Anne Tergesen,“Firms Curb Raids on 401(k)s,” Wall Street Journal, April 3, 2017.

40 CIBC,“New Tax‐Free Savings Accounts.”

41 Munnell and Webb, p. 17.

42 Investment Company Institute,“Appendix: Additional Data on IRA Ownership in 2016,” January 2017, p. 5.

43 Hungerford, p. 12.

44 Hubbard was talking about Lifetime Savings Accounts proposed by the George W. Bush administration in 2003. Like USAs, those accounts would have been funded with after‐tax contributions, and allowed for tax‐free withdrawals at any time for any reason. Quoted in Tyler Cowen,“The Case for Lifetime Savings Accounts,” Marginal Revolution, January 20, 2004.

45 HM Revenue and Customs, Individual Savings Account (ISA) Statistics, p. 25. Data for 2013–14.

46 Canada Revenue Agency, Table 1C.

47 Ibid., Table 3C.

48 Cited in Investment Company Institute, Fact Book, 2016, p. 134.

49 Authors’ calculations based on HM Revenue and Customs data.

50 Authors’ calculations based on Canada Revenue Agency data.