In a perfect world, tax policy would be neutral toward health expenditures. Consumers would make medical and health insurance decisions based on the value of different alternatives, free from tax distortions. Some analysts are proposing limiting tax distortions by capping the tax benefits for employer-sponsored insurance. Others advocate giving deductions or credits to individuals to purchase insurance and medical care directly. These ideas have merit, but a better route to health care reform would be to expand health savings accounts.

HSAs were created by Congress in the Medicare Modernization Act of 2003. They combine high-deductible health insurance with a personal savings account for medical expenses. Money deposited into HSAs by employers or employees is untaxed. HSA funds may be withdrawn tax-free for medical purchases, and any unused balances grow tax-free indefinitely.

As they exist today, HSAs make consumers more costconscious users of routine care, but they still encourage excessive coverage and do not give consumers full control over their health care dollars. HSAs do reduce the tax bias toward excess coverage, but Congress requires HSA holders to purchase insurance, and it imposes coinsurance limits that require some to buy more coverage than they want. Also, HSAs only marginally offset the bias in favor of employer-provided coverage. Those who obtain HSAs on their own can make pre-tax deposits, but they must purchase the mandated insurance with after-tax dollars. Thus, current HSAs only modestly reduce the tax code’s distortion of health care markets.

Expanding HSAs into larger, more flexible accounts, however, can bring more equity to the tax code, and more choice and competition to the health care sector. Three changes are necessary to create large HSAs:

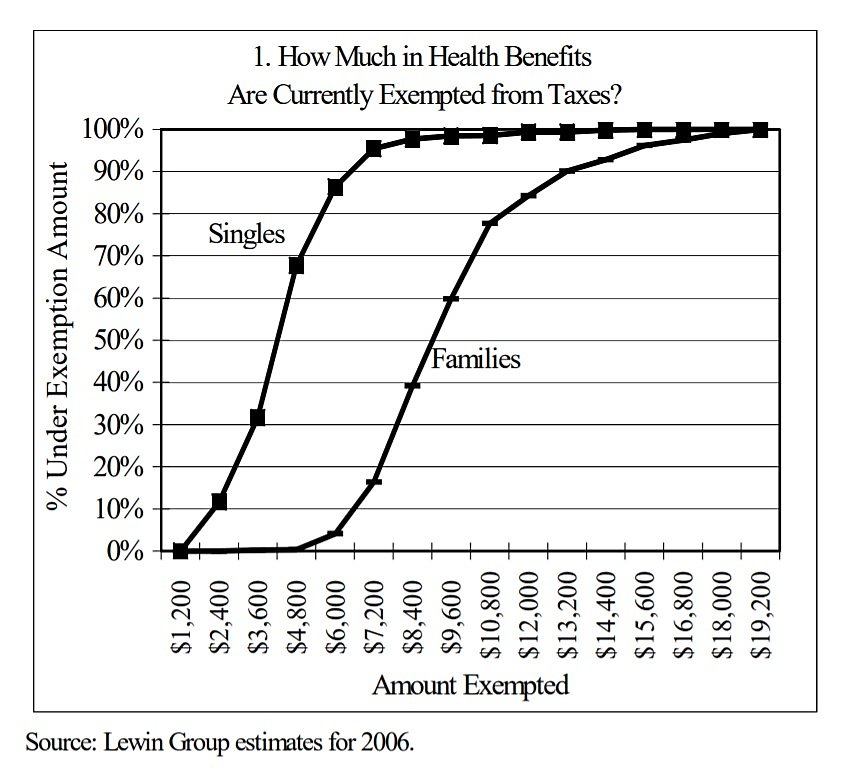

- Increase HSA contribution limits to $8,000 for singles and $16,000 for families;

- Eliminate the requirement that HSA holders obtain health insurance; and

- Allow tax-free HSA withdrawals for health insurance premiums as well as health care.

These changes would give workers full ownership and control over all their health care dollars, and would vastly expand choice and competition in health care markets.