Introduction

Among the key animators of progressive politics are the mitigation of climate change, assisting the underprivileged, and a revived interest in antitrust measures to break perceived areas of corporate dominance. It’s a curiosity, then, that more progressives have not embraced the cause of dismantling the Jones Act. In fact, one would be hard-pressed to find a more clear-cut example of a law that privileges corporations while harming marginalized communities and the environment than this century-old law.

The Jones Act—more formally, Section 27 of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920—restricts the transportation of goods between U.S. ports to vessels that are mostly U.S.-crewed and owned, as well as U.S.-registered and U.S.-built. While a gift to U.S. shipping and shipbuilding firms, the law comes at a net cost to the broader economy. The combination of reduced competition and the mandated use of ships that are expensive to build—four to five times more costly than those constructed abroad—and expensive to operate makes for expensive domestic transport. That’s no small thing in a country as large as the United States, where the efficient movement of goods is key to enabling trade across its vast expanse.

Disproportionate Impact

Although harmful to all Americans, the law’s impact is disproportionately felt by those living in the country’s noncontiguous states and territories, where alternative forms of transport such as trucking and rail are either greatly limited, such as in Alaska, or nonexistent, such as in Puerto Rico. Home to more than three million people, the island has a larger population than Alaska, Hawaii, and all other U.S. territories combined. Already struggling economically, Puerto Rico was dealt a further blow when Hurricane Maria struck in 2017, leading to billions of dollars in damage and hundreds of lost lives. The island’s distress is perhaps most starkly evidenced by a stunning 43 percent poverty rate.

Although the sources of Puerto Rico’s travails are multifold, the Jones Act counts among them, as documented by numerous studies and analyses. As far back as 1930, economist Victor S. Clark noted the Jones Act’s handicapping role on Puerto Rico’s economy, while in 1966 a government commission called for modification of U.S. shipping laws to assist the island. Just last year the RAND Corporation cited the Jones Act as a leading impediment to the island’s economic growth. In addition, numerous progressive voices have identified the Jones Act as a source of harm to Puerto Rico, including Paul Krugman, Joseph Stiglitz, and Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D‑NY).

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@RepAOC), Twitter, September 20, 2020, 3:36 p.m., https://twitter.com/RepAOC/status/1307765560948727811.

We must also abolish PROMESA, whose extreme austerity measures have closed public schools and defunded other critical public services. We must lift the Jones Act, which has exploited Puerto Rican consumers and strangled the economy

Americans across the ideological spectrum may not fully agree on how best to bring prosperity to Puerto Rico, but there should be widespread consensus that federal policy should, at the very least, stop hurting the island’s economy by subjecting it to some of the world’s most expensive shipping.

This isn’t just a matter of economics, but equity and simple fairness. Supporters of the Jones Act claim that the law is necessary for national defense by providing ships, mariners, and a shipbuilding capability that can be mobilized in time of war. Even if one accepts this logic, the use of direct and transparent subsidies would be a superior approach to the Jones Act with its opaque and uneven costs. This burden should not be disproportionately borne by a poverty-wracked island that lacks voting representation in Congress or the ability to cast ballots in presidential elections.

Companies Win, Consumers Lose

In sharp contrast with the citizens of Puerto Rico, the shipping companies that transport goods between the island and the U.S. mainland benefit tremendously from the Jones Act. The law’s prohibition on foreign ships means that these companies don’t have to worry about lower-cost competitors. Perversely, these firms even benefit from the Jones Act’s mandate that they use expensive U.S.-built ships. The added costs are simply passed along to the consumers in the form of higher shipping rates, while the high cost of acquiring vessels serves as a barrier to market entry and potential competition. The result in Puerto Rico—like Alaska, Guam, and Hawaii—is an oligopoly, with just two firms controlling 85 percent of the container capacity for shipping with the U.S. mainland.

This limit on competition has enabled predatory corporate behavior. Freed from worries about new firms entering the market, companies serving Puerto Rico were found to have colluded on shipping rates from 2002–2008 in what the Department of Justice called “one of the largest domestic price-fixing conspiracies ever investigated by the United States.” Prosecution of the case resulted in several guilty pleas by shipping executives, who were given prison sentences and hefty fines. While thanks should be given for the government’s uncovering of this collusion, the anti-competitive environment that made it possible—which still persists—is a direct result of the Jones Act’s barriers to market entry.

Environmental Toll Adds to Harms

But consumers are far from the Jones Act’s only victims: the law inflicts a significant toll on the environment as well. By disincentivizing the use of water transport—by far, the most carbon-friendly means of transporting goods—the Jones Act serves to drive up the emission of greenhouse gases (Figure 1). Rather than transporting cargo by water, a portion is instead diverted to more carbon-intensive modes, such as trucking and rail.

While more than 36 percent of freight is transported by sea and inland waterways in the European Union (EU), ships and barges account for a mere 6 percent of freight transport in the United States. Geography no doubt explains a significant amount of the discrepancy, but the deadening hand of the Jones Act surely figures here as well. Although containers are regularly transported by water within the EU, the Congressional Research Service points out that essentially all such movements in the United States take place by truck or train.

Even when sea transport is used, the Jones Act also means that the ships used to transport goods themselves are less environmentally friendly than would otherwise be the case. By dramatically raising the cost of new ships, the Jones Act results in older—and less efficient—vessels being kept in service for much longer than is commonly found in other countries. Examining this and other harms caused by the law, economist Timothy Fitzgerald has calculated that the potential environmental gains of repealing the Jones Act would range from $109 million to $8.2 billion.

And the environmental costs rise further still when more indirect factors are considered. As Fitzgerald notes, the increased cost of domestic transport resulting from the Jones Act diverts industry to foreign soil, where environmental standards are less stringent.

Other examples of the law’s harm are more straightforward. In a bid to reduce carbon emissions, both state and federal policies have been encouraging the development of offshore wind power. Unsurprisingly, the Jones Act plays a deleterious role here, too. Constructing offshore wind farms requires the use of highly specialized vessels that transport turbine components from ports to offshore points and then install them. But no such vessels currently exist in the Jones Act fleet, so inefficient workarounds must be used.

Wind turbines installed near Block Island, for example, required the use of Jones Act–compliant feeder barges that transported the turbine components from a nearby port to a foreign installation ship to avoid violating the law. Installing turbines off the coast of Virginia, meanwhile, necessitated a foreign installation vessel transporting the components from Canada. By making the voyage international, the vessel was freed of the Jones Act’s constraints and could successfully perform the installation. But this came at a substantial cost: while constructing the turbines would have taken a matter of weeks in Europe, the Virginia project required a year thanks to the Jones Act.

Small wonder the New York Times described the law as the project manager’s biggest headache.

A Failed Law

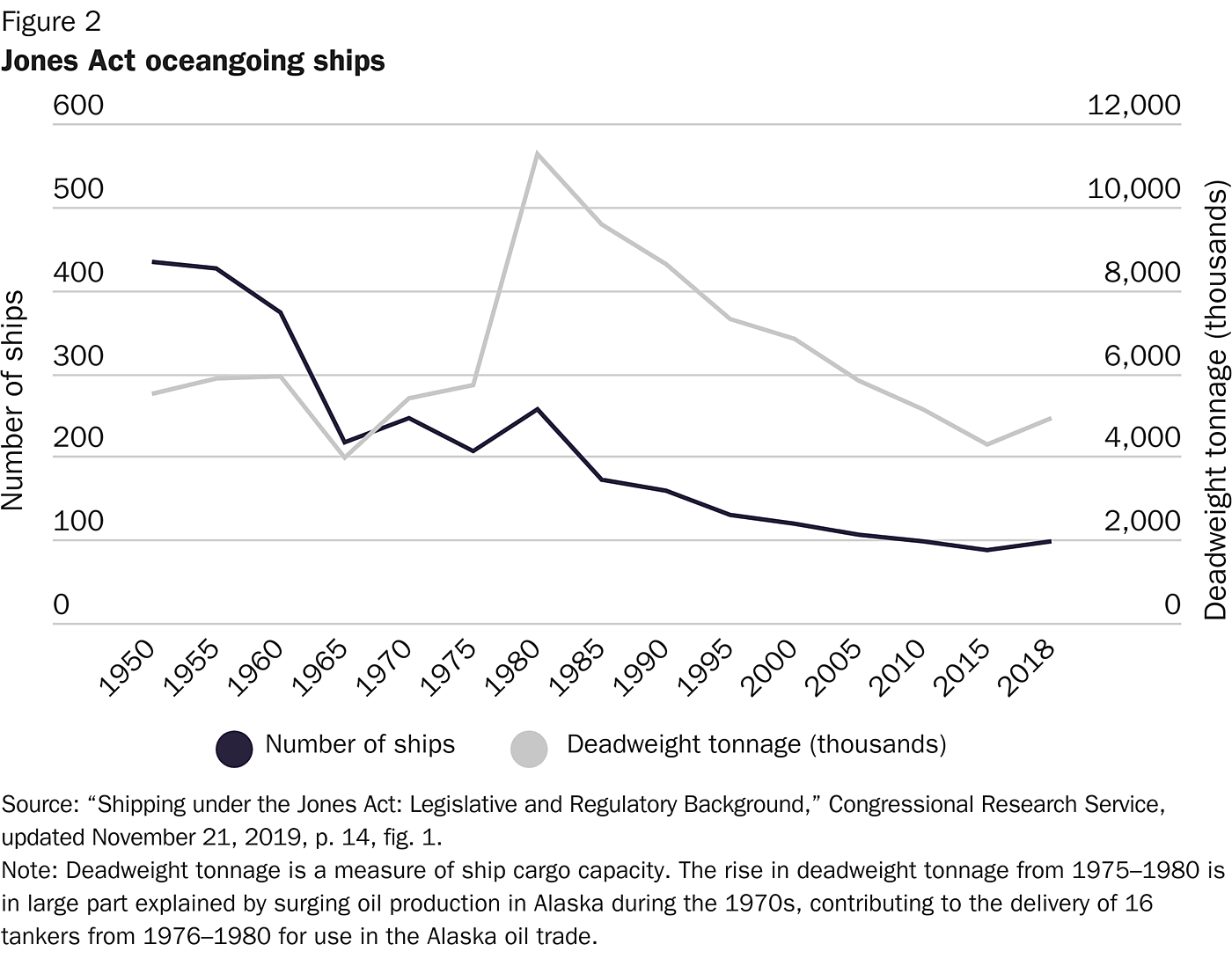

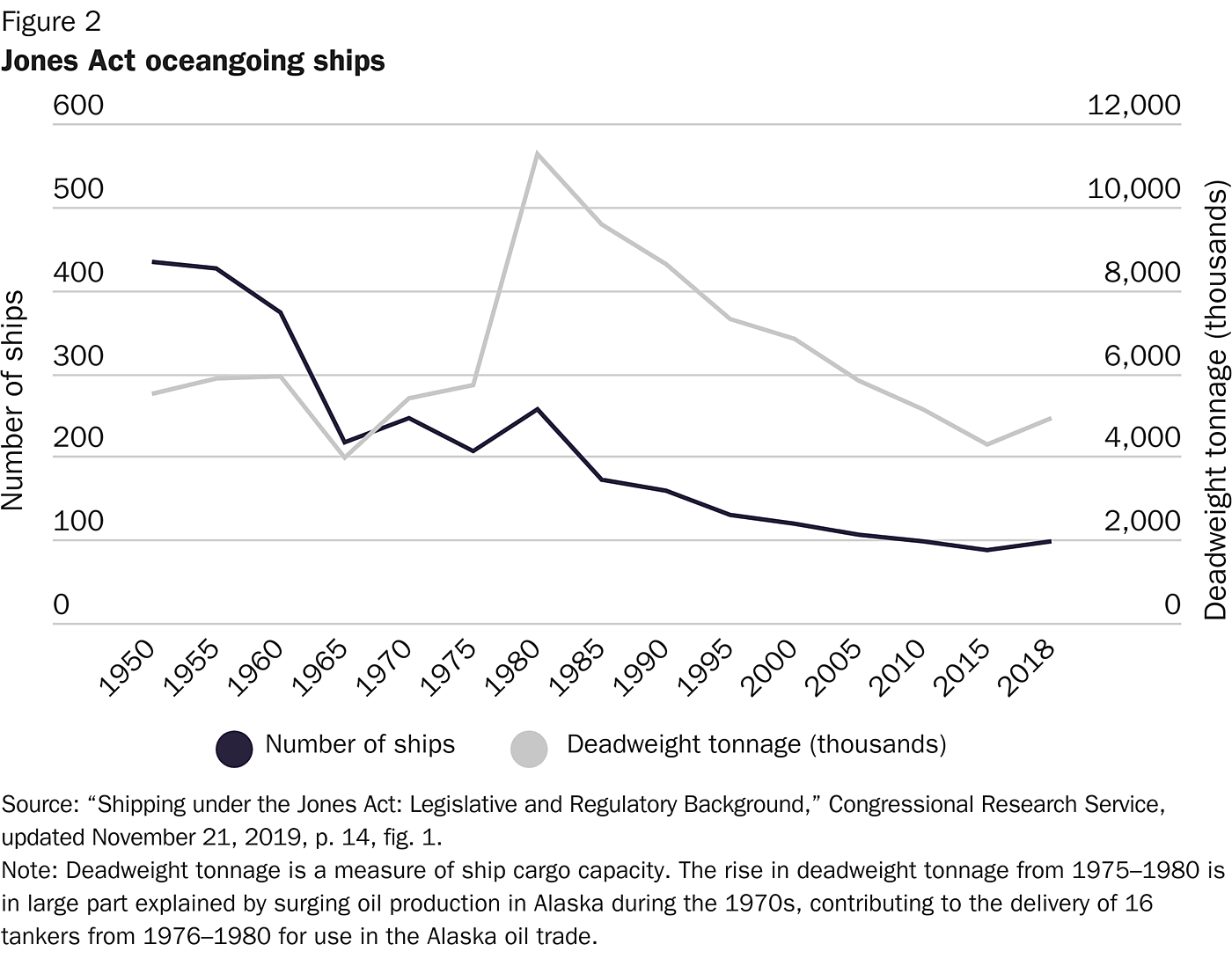

Adding insult to injury, the protectionist law has failed to generate a vibrant domestic maritime industry (Figure 2). Jones Act ships are so expensive that they are essentially only used where there is no alternative form of transport. Typically, this means carrying goods to and from the country’s noncontiguous areas and transporting petroleum products to areas of the U.S. mainland that are not served by pipelines. Meanwhile, the shipyards that build these vessels are so uncompetitive that few commercial ships are actually built. The result is an oceangoing fleet whose number has more than halved since 1980 and shipyards that collectively construct a mere two or three ships per year.

The law’s costs and benefits are completely out of balance.

Yet still the Jones Act endures. Shipyards and shipping companies reap the added profits of reduced competition in a captive domestic market, while everyday Americans, including some of the country’s poorest citizens, pay the price. The injustice is further compounded by the environmental toll exacted. The Jones Act is unwise, unjust, and it isn’t working. Creating the fairer and more equitable society that progressives seek must include the reform, if not full repeal, of this odious law.

Featured Project

Cato Project on Jones Act Reform

The Cato Institute aims to shake up this status quo by shining a spotlight on the Jones Act’s myriad negative impacts and exposing its alleged benefits as entirely hollow. By systematically laying bare the truth about this nearly 100-year-old failed law, the Cato Institute Project on Jones Act Reform is meant to raise public awareness and lay the groundwork for its repeal or reform.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.