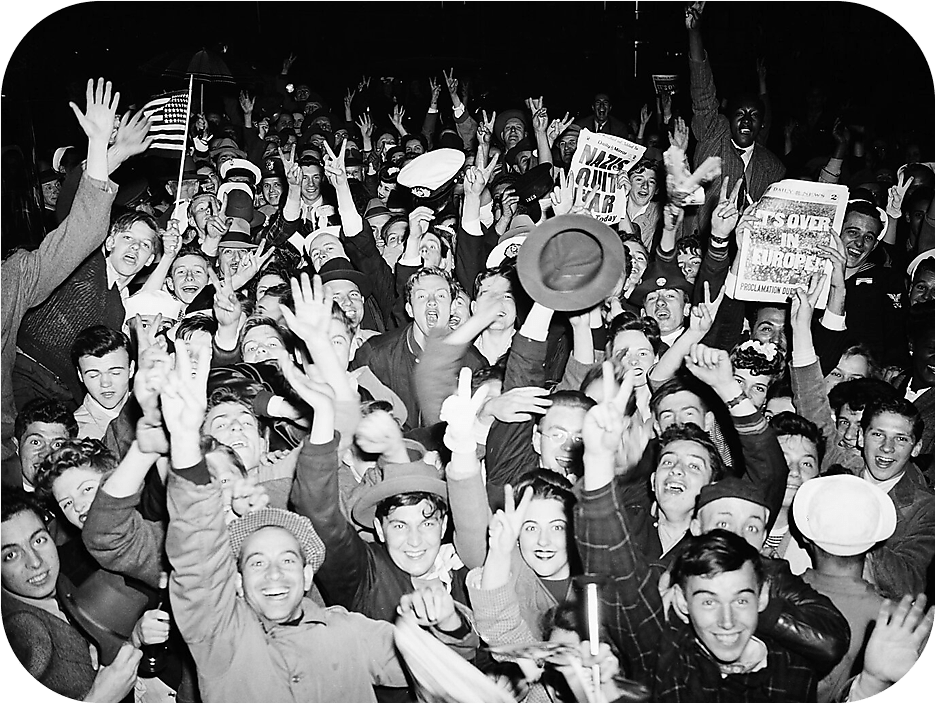

The COVID-19 pandemic has ballooned federal debt. Huge relief programs, alongside collapsed tax revenues in 2020, lifted debt from 79.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2019 to 99.6 percent in 2021. As a result, the federal debt stood at its highest level since World War II.

The Government Debt Iceberg

The Unprecedented Fiscal Imbalance Lurking below the Surface

When extreme events such as unexpected wars or pandemics hit, letting borrowing rise to fund one‐off spending or revenue shortfalls might make economic sense. Allowing federal debt to act as a shock absorber avoids sharp, destructive tax rate hikes or spending cuts. Instead, the crises’ costs can be spread over future generations.

In fact, too much focus on the Covid-19 red ink risks us losing focus on a much graver fiscal challenge to come.

Former Cato scholar Jagadeesh Gokhale has likened the U.S. federal debt problem to an iceberg. The official debts we see above the waterline reflect the consequences of historic borrowing. What really threatens our fiscal future are debts hidden underneath the surface: the contingent liabilities of promises that have been made to an aging population.

If left unchecked, it’s these current entitlement programs—Social Security and Medicare—that will really ratchet up federal debt over the coming decades.

But don’t take our word for how dangerous this would be. Before the pandemic, the current Secretary of the Treasury Department herself said:

“The U.S. debt path is completely unsustainable under current tax and spending plans.”

—Janet Yellen, secretary of the Treasury in the Biden administration

Yes, projecting so far into the future brings huge uncertainties, not least because future politicians might change tax and spending policies to avert this outcome.

But the underlying scale of the coming pressure set by current policies is unprecedented.

In fact, the economic fundamentals of the coming decades are such that it will become much more difficult to keep debt under control—let alone get it to fall, which happened after World War II.

Post-1945, debt levels fell in part because politicians slashed spending due to demobilization and then ran budget surpluses (excluding debt interest) for all but a few of the next 30 years.

Today, large structural deficits already exist, politicians want new unfunded government programs…

…and a tidal wave of age‐related spending already lies ahead.