Building codes that regulate how new buildings can be built serve essential safety purposes. They fall squarely within states’ police power to protect residents’ health and safety. However, few current building codes achieve their ostensible objectives in a cost-effective way.

Building codes in the United States are largely based on model codes developed by a nonprofit organization called the International Code Council (ICC), and its code development process fails to elevate technical analysis. The ICC should slow down its code change process, provide benefit–cost analysis of its new and existing rules, and replace its unwieldy rule-change adoption process, in which municipal employees vote on changes, with one in which a small group of well-informed stakeholders adopts code revisions.

Building code rules can add significantly to the cost of constructing new housing. Codes have ballooned in length and complexity, especially of late: A 2022 trade association member survey found that building code changes adopted just since 2012 account for 11 percent of the cost of building new apartments (Emrath and Walter 2022). Some building code requirements that deviate from international norms are beginning to draw scrutiny. A long-standing rule in place in most US communities requires apartment buildings over three stories to have two staircases. In most other countries, including those with death rates from fire well below the United States, taller multifamily buildings can be built around a single staircase, allowing for more efficient floorplans (Eliason 2021).

A reform effort to end the second-staircase requirement has shown a light on the need to improve the building code adoption process more broadly. In addition, state and local policymakers are asking tough questions about whether their building codes based on the ICC model are compatible with their housing affordability objectives.

A Brief History of US Building Codes

Early American building codes began as a response to urban conflagrations that caused enormous loss of life and property. Following its 1871 fire, Chicago developed one of the country’s first building codes. After a period of city-specific building codes, regional model codes began to take root early in the 20th century. Because of both the implementation of sensible building codes and—perhaps more importantly—rising living standards, cities and buildings are much less prone to fire losses today.

The ICC was founded in 1994 as a 501(c)6 nonprofit organization with the intention of reconciling those disparate regional codes into a single national model (Ching and Winkel 2018). Despite the “international” in its name, the I‑Codes are rarely used outside the United States. While other organizations also provide model building codes and standards, the I‑Codes are foundational to most state and local building codes today. The ICC publishes several model codes, with its International Residential Code (IRC) providing regulations for one- and two-family development (generally including townhouses) across the United States and its International Building Code (IBC) providing the regulatory foundation for multifamily and other types of developments. Not all the codes relate to safety: The International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) is an increasingly important source of energy efficiency construction mandates.

States vary in how they adopt the ICC’s model codes. Some adopt the I‑Codes in their entirety, others adopt amendments in a statewide building code, and in some states local governments have the authority to make their own code amendments. One purpose of the ICC was to rationalize codes across the country and make it easier for developers and homebuilders to work across jurisdictions. However, important variations in codes across borders remain. State and local amendments to the code allow for rule differences that make sense—particularly in dense urban areas—but such differences can create barriers to firms building across multiple jurisdictions, particularly hampering offsite construction.

The Mechanics of Code Change

The ICC updates its codes over three-year cycles in a process that relies principally on volunteers from the government, industry, and the nonprofit sector. Anyone can serve as a proponent for a code change by drafting revisions to the code, providing a rationale, and submitting the change to the ICC. Stakeholders and members of the public can submit comments, and the ICC holds a committee hearing on each proposed change. People who are interested in serving as committee members can apply to do so, and the ICC Board, made up of code officials, selects among applicants. At least one-third of volunteer committee members must come from government, and they also include representatives from industry and nonprofits.

Following the first committee hearing, the ICC offers an opportunity for public comment, and proposed rules that receive comments go to a second committee hearing. Committee recommendations to adopt, modify, or reject proposed changes are opened up to an additional public comment period. Proposed rules that do not receive public comment are included on a consent agenda. Rules that do receive comments advance to an in-person Public Comment Hearing where public sector members vote to approve, modify, or disapprove them. The ICC requires that public sector voting members “be an employee or a public official actively engaged, either full or part time, in the administration, formulation, implementation or enforcement of laws, ordinances, rules or regulations relating to the public health, safety, and welfare.” Many government members are code officials, but they can be as diverse as local employees who work on environmental policy, mayors, or government contractors who are authorized to approve building designs.

Rules that receive votes for disapproval in both committee hearings and the Public Comment Hearing do not advance further. Rules that advance out of Public Comment Hearing go to an Online Governmental Consensus Vote where additional public sector members can weigh in on proposed rules during a weeks-long period. Rules that receive a final vote for approval or approval as modified will be included in the following edition of the I‑Codes.

Benefit–Cost Analysis in the ICC Code Development Process

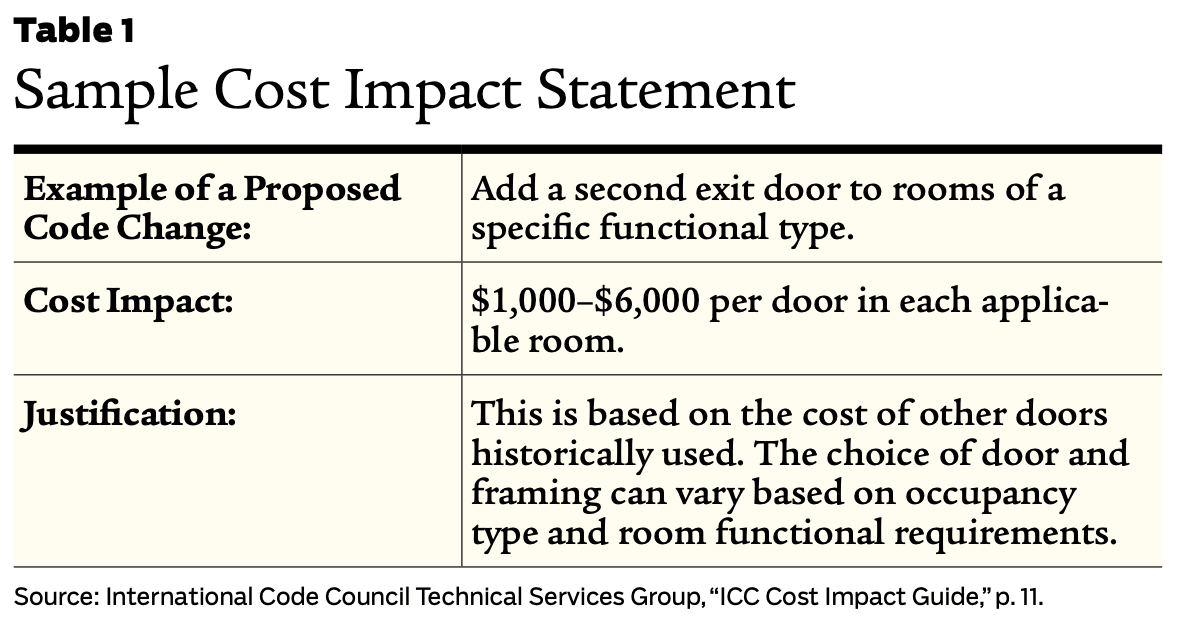

The ICC requires proponents of code changes to include estimates of the cost of a proposed rule’s effect on construction costs. Table 1 provides an example from ICC literature.

However, many cost estimates submitted by code change proponents are devoid of rigor. For example, one proposal submitted for consideration in the 2027 I‑Codes is a requirement that penetrations through floors and ramps in parking garages (such as pipes) include firestop systems to reduce the potential of a fire spreading between floors. The proponent includes a cost estimate of $35–$50 per penetration, but the government officials who will ultimately vote on this code change aren’t told how much this might increase costs for parking garage users. Their focus on costs to the construction firm provides a lower cost estimate than what consumers will ultimately pay, which will include overhead and, in some cases, ongoing operating expenses. At the committee hearing for this rule, members of the public and committee members pointed out that it is unclear what benefit, if any, would come from this additional cost, given that parking garages often have large openings between floors along their ramps as well as along exterior walls. Nonetheless, the committee recommended approval of the proposal.

Proponents of a code change often say their proposal will have “no cost impact” because the proposal is a clarification. Sometimes these proposals are true clarifications, but other times “clarifications” greatly change how the code will be interpreted by code officials. For instance, one recent proposed change submitted to both the IBC and the International Existing Building Code (IEBC) would mandate audio-visual communication devices in elevators so that hearing-impaired passengers can communicate if they are trapped in one. The impact statement for the IBC claimed the change would be a clarification with no added costs, but the IEBC cost impact statement reported it would increase costs by up to $5,000 for each new elevator (Smith 2024). This vast disparity demonstrates the inaccuracy that the ICC process allows.

In the ICC process, proponents of rule changes explain their justification for the change, but the ICC does not suggest these components of code change proposals include monetized benefits, nor do proponents generally provide them. Reason statements often include justifications such as “improve life safety” without any effort to quantify the extent to which a code change will reduce deaths and injuries or protect property.

ICC cost impact estimates are simple to read and easy to produce, but they lack the necessary information for informed decision-making. The ICC’s weak requirements for cost analysis pave the way for rhetoric, rather than reason, to drive code changes. In response to concerns about the costs of code changes, change supporters often use facile tactics such as postulating that any saved life is invaluable and thus the proposed change is worthwhile—a tactic that often works. Each new building code requirement that drives up the cost of construction reduces the amount of new housing that will be feasible to build. Rules that make new buildings safer but decrease new construction involve risk–risk tradeoffs (Dudley and Brito 2012) because they increase the number of people who live in older buildings that are generally less safe in many dimensions relative to what would be built today with or without new code requirements.

A Circle of Unaccountability

The ICC review process is open and offers many opportunities for engagement, but it does not elevate scientific evidence to inform decision-making. Regardless of the quality of the analysis provided for each proposed code change, voters cannot reasonably be expected to become well-informed on the number of rules proposed to the ICC each code cycle. In the 2019 code cycle, nearly 2,300 public sector members cast close to 370,000 governmental consensus votes. The ICC has about 15,000 public sector members, so most of them didn’t find it worth their while to participate. Knowing that their vote will have only a small probability of affecting the outcome disincentivizes them from spending the time to study each proposed rule even if it were feasible to do so.

The state and local elected officials who adopt the I‑Codes ultimately have the responsibility for ensuring their building regulations serve their constituents. However, because adopting the I‑Codes or an amended version of them is the generally accepted way to regulate buildings in the United States, these policymakers elude scrutiny by using the ICC to form the basis of their building codes. And because the governmental consensus voters have the final say on rule changes, the ICC can claim the code originates with the governments that implement it.

While the government officials who vote on code changes may have a keen understanding of how new rules may or may not be enforced, they have a narrow perspective on the code and code changes. They generally do not have backgrounds in architecture or engineering, which would be necessary to independently evaluate many proposed new rules. Unlike the elected officials who ultimately adopt model codes, building inspectors are not able to weigh the benefits of new requirements against other public policy objectives such as new housing supply, housing affordability, and quality of life compromises that code components may require. Because elected officials have largely outsourced this duty to the ICC, they too are not currently taking responsibility for creating a building code that meets the pluralistic objectives they are responsible for balancing.

Improving Incentives in Code Development

Reforming US building codes to better meet the public’s needs is a thorny challenge. It’s easy to imagine systems of building code development that support a market process and improved construction methods over time. Hypothetically, a pure performance-based code could allow builders to meet safety and energy standards in increasingly cost-effective ways, insurance companies could develop safety standards for buildings they insure, or states and localities could allow builders to choose between the ICC codes and those of countries where building codes deliver safer, more efficient buildings at lower cost.

But it is difficult to imagine state and local officials moving the political process away from the ICC. The ICC provides a service that would be costly for them to replicate, and it allows them to avoid the responsibility of code development. Policymakers can pick and choose when to default to the I‑Codes and when to make their own amendments. Industry participants benefit from the opportunity to support rules that would require buildings to incorporate their products. The public loses by having to pay for code components that are adopted with insufficient concern for social costs and risks.

Despite the forces that support the status quo, there are indications of limits on stakeholders’ willingness to accept costly ICC mandates. For instance, starting with the 2009 edition, the IRC has included an automatic fire sprinkler mandate for one- and two-family houses. In part because of trade association opposition to the change, only California and Maryland have implemented this requirement at the state level, and 29 states preempt local government officials from requiring sprinklers. A study analyzing the benefits and costs of sprinkler mandates in Massachusetts found that requiring fire sprinklers for all one- and two-family houses does not pass a cost–benefit test (Zemel 2023).

After a small group of architects and activists began drawing attention to the requirement for multifamily buildings to have two staircases, policymakers in several states passed laws establishing committees to study reforming their codes to allow multifamily buildings up to six stories to have a single staircase, and some states have gone further to legalize these buildings. If the ICC does not want policymakers to take the code development process into their own hands, it should adopt a more cost-conscious code development process.

Three major reforms could put the ICC on track to produce a code that better aligns with the public interest. First, the ICC should extend the time between editions of its code. When the process of creating the 2027 edition of the I‑Codes began, no jurisdictions had yet adopted the 2024 codes. Some large jurisdictions are still using the 2015 IBC. Rapid changes help the ICC sell codes, but they don’t provide time for codes’ unintended consequences to be revealed. Better-informed codes could be developed by extending the time between editions to at least six years.

Second, the ICC should hire staffers to analyze proposed code changes’ costs and benefits. These hires should include subject matter experts as well as economists with the skills necessary to conduct benefit–cost analysis. Such a staff should begin a process of retrospective review, evaluating whether existing code components merit inclusion going forward. Professional benefit–cost analysis would throttle the number of new rules that could be analyzed in each cycle and nudge ICC committees toward considering reforms with the potential to reduce costs while maintaining safety standards. The ICC promotes itself as a neutral convener of stakeholders, but its code development process lacks neutral analysis. The ICC is in a good position to provide needed study on the effects of rule changes.

Finally, the ICC should extend the IECC reform that eliminated the governmental consensus vote to the development of all its codes. Direct democracy is no way to craft a body of complex, interlocking regulations. Rather, a smaller group of representative stakeholders should be making decisions on which code changes to adopt. Code officials and other municipal representatives need a seat at the stakeholder table, but they should be charged with carefully weighing in on a manageable number of rule changes before their committees, with the time needed to deliberate on each proposal. They should not be voting on myriad proposed rules outside their expertise that they have neither the time nor training to evaluate methodically.

The ICC’s model codes have an enormous effect on the quality and affordability of the buildings we spend most of our lives in, but their code development process lacks the rigor that such an important body of rules deserves. Should the ICC fail to adopt reforms to its process for code creation, state and local officials should find another source for a model code or develop the internal capacity to write their own codes if they want building codes that support their housing affordability goals.

Readings

- Ching, Francis D.K., and Steven R. Winkel, 2018, Building Codes Illustrated, 6th ed., John Wiley and Sons.

- Dudley, Susan, and Jerry Brito, 2012, Regulation: A Primer, Mercatus Center at George Mason University and George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center, p. 83.

- Eliason, Mike, 2021, Unlocking Livable, Resilient, Decarbonized Housing with Point Access Blocks, Larch Lab.

- Emrath, Paul, and Caitlin Sugrue Walter, 2022, “Regulation: 40.6 Percent of the Cost of Multifamily Development,” National Association of Home Builders and the National Multifamily Housing Council.

- Frost, Lionel, and Eric Jones, 1989, “The Fire Gap and the Greater Durability of Nineteenth Century Cities,” Planning Perspectives 4(3): 333–347.

- Housing Affordability Institute, 2022, “Regulatory Marketing.”

- Smith, Stephen, 2024, Elevators, Center for Building in North America, July.

- Wermiel, Sara E., 2012, “Did the Fire Insurance Industry Help in the 19th Century?” Flammable Cities: Urban Conflagration and the Making of the Modern World, Greg Bankoff et al., eds., University of Wisconsin Press.

- Zemel, Felix I., 2023, “Reframing How Complex Building Code Proposals Are Assessed: The Case of Home Fire Sprinklers,” doctoral dissertation, Tufts University School of Medicine, August, p. 68.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.