Looking at a recent, pricey electricity bill—issued by a utility that my state of residence, California, regulates intensely —I couldn’t help wondering: How much worse could it be if California didn’t regulate the monopolist at all?

There are explanations for the bill, of course. Californians pay very high prices for electricity in part to fund costly utility-run energy, environmental, and welfare programs mandated by the state but not needed for providing the service.

This got me thinking about something that, on the surface, seems entirely different: social media. During the pandemic, federal authorities pressured major social media companies to limit discussions of important pandemic and political issues. The authorities justified their pressure by saying it was necessary to combat misinformation and disinformation, though some of the discussions they wanted suppressed—e.g., skepticism about the effectiveness of masking, suspicions about the virus’s origin, discussions about the efficacy of various treatments—seemed both reasonable and important. Regardless, though the federal government didn’t itself censure these discussions, its efforts to get social media companies to do so certainly violated the principles underlying the First Amendment’s free speech protections.

There is a link between these government initiatives. According to traditional theories of regulation, government should protect the public from utility monopoly power and enforce no restrictions on the content of public discourse. But instead, we see authorities doing the opposite to pursue their own objectives. This practice goes beyond prior theories of regulation into something new: the commandeering of private entities’ market power by government for its own ends, ironically by causing the same types of consumer harm—higher prices, service losses, and censorship—that government is supposed to guard against.

Commandeering California’s Electricity Utilities

These are sizeable interventions. Between added expenses and cross subsidies between customers, California’s commandeering of its three major power utilities involves over a quarter of the utilities’ $40 billion in annual revenues. Pacific Gas and Electric, Southern California Edison, and San Diego Gas and Electric collectively serve three-quarters of the state’s households under exclusive monopoly franchises and are regulated by the California Public Utilities Commission (CPUC). Virtually every aspect of their operations and interactions with customers is supervised, often actively.

Oversight like California’s is often justified by the natural monopoly version of the Public Interest Theory of regulation. The notion is that economies of scale make a single network firm the least costly provider, and thus economic forces will promote complete market consolidation. The resulting monopoly will thus need to be regulated by government lest it overcharge its customers, costing them money and inducing them to use less of the service they need. The remedy is some form of governmental control over utility expenses, investments, managerial efficiency, and methods of pricing, thus limiting what customers pay to what regulators deem fair prices covering only necessary costs. Even absent proof of the “single firm is cheapest” concept (which is very difficult to test), intuitive concerns about such entities are widely recognized as justifying regulation.

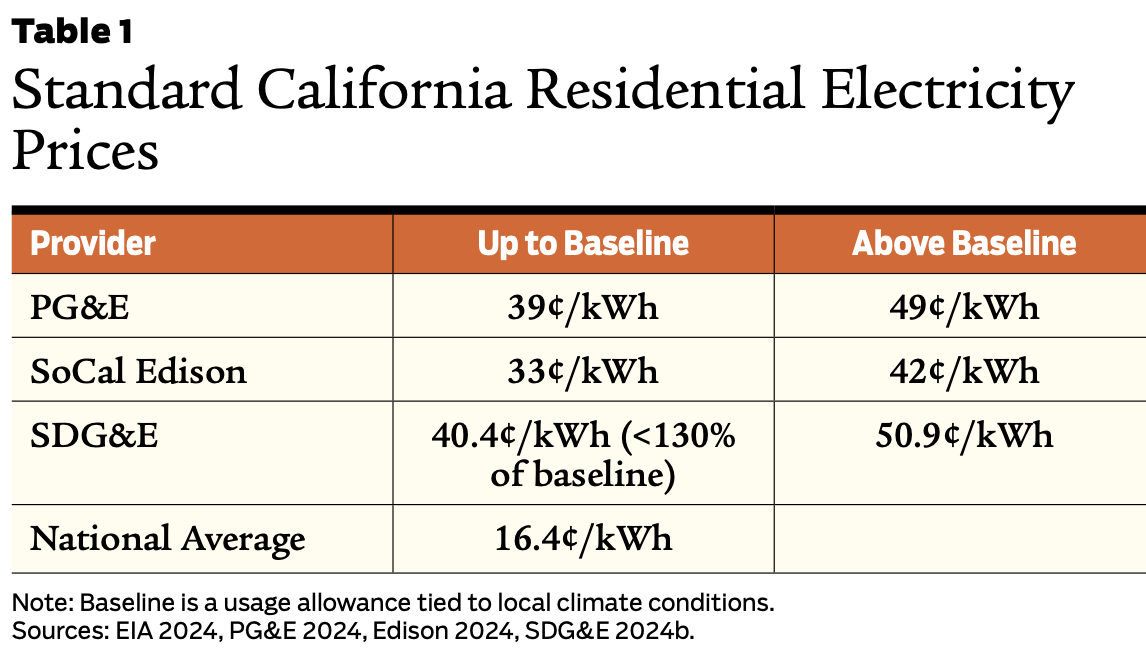

Yet, despite intensive regulation, the retail electricity prices are staggeringly high for these California utilities. Table 1 shows them compared to the national average. These prices are elevated because of three types of California government initiatives—that is, three types of state commandeering of the utilities’ monopoly power. The first is mandated programs, funded through utility bills, whose costs fall on customers. The second is an assignment of liability to these utilities for wildfire damages they may not have caused. The third is mandated transfers between customers for an environmental initiative, where some pay higher utility bills so that others can more easily purchase rooftop solar systems. In other words, electricity prices have been raised by added costs for activities mandated by government, and by shifting the responsibility for paying the utility’s (overall) expenses among customer groups. The prices in Table 1 reflect both effects.

Program costs charged to customers / Through their utility bills, Californians pay for multiple government programs that are not part of the normal operations of a business. Instead, these programs reflect the will of state lawmakers and regulators, expressed off-budget. Admittedly, some nonregulated companies engage in similar activities (such as research and development), but they do so using corporate funds rather than raising the prices their customers pay.

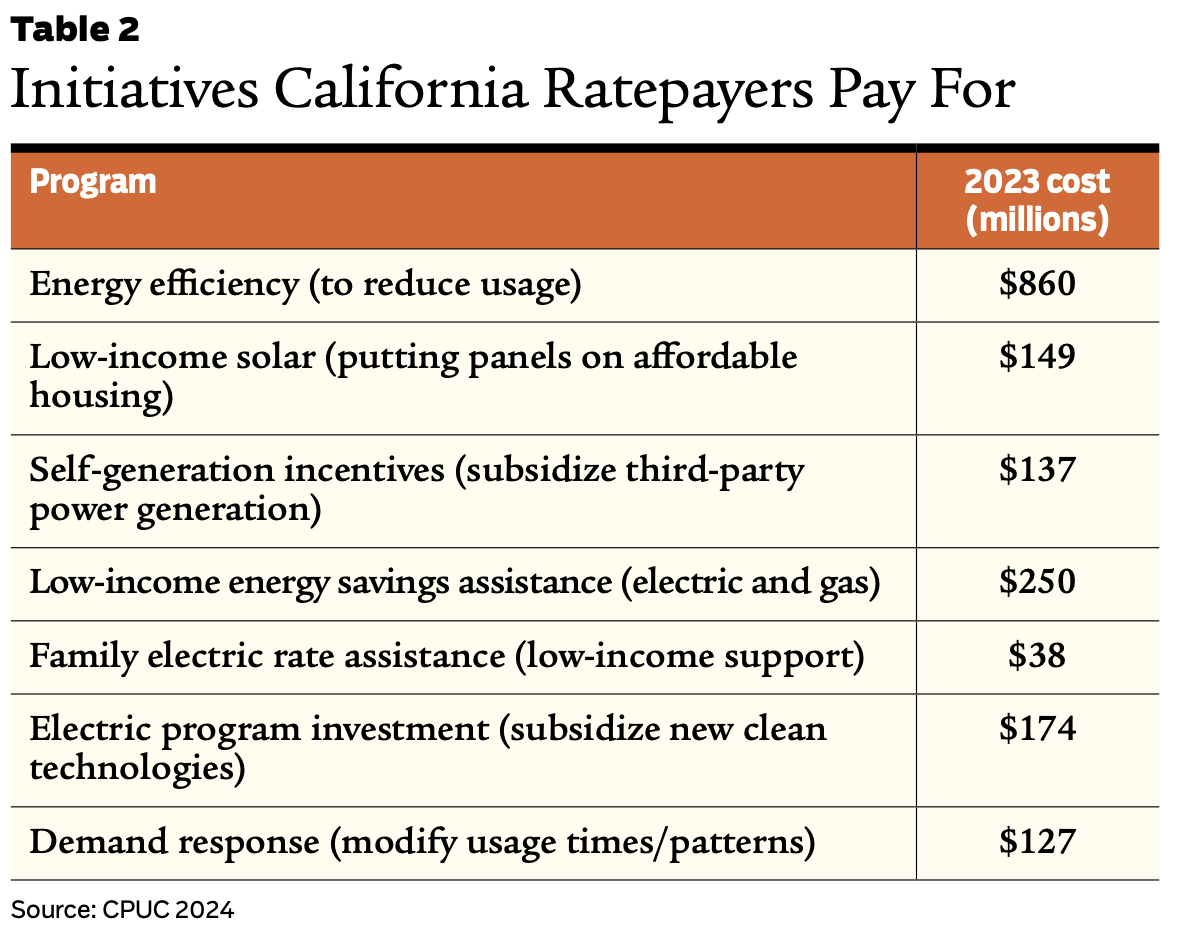

Table 2 lists some of the more prominent of these California initiatives. The list is not complete, a few elements may fit with normal utility operations (such as some demand response), and a Public Purpose Programs funding surcharge is levied on top of usage prices for So Cal Edison and SDG&E (but included in PG&E’s). Still, the total cost of these initiatives is substantial, at $1.74 billion per year.

As with any set of policies, one can debate these initiatives’ merits. The economic case for energy efficiency subsidies, for example, is limited to circumstances California doesn’t face because its elevated electricity prices (far above marginal social cost, including an allowance for carbon emissions) already give customers an excessive incentive to conserve. As another example, public subsidies for new technology and research and development can be helpful (perhaps for progress against climate change), but it is another question how expert state regulatory officials may be at handing them out.

Advocates for these and other programs would beg to differ, and their viewpoint has largely prevailed in California, as the list of approved efforts shows. But the nature of the exercise—funding through use of utility monopoly power against customers—remains the same whether the results are beneficial or wasteful.

Liability deep pockets / Uniquely, a California appellate court decided in 1999 that a utility must pay all damages for any wildfire connected to its facilities, regardless of fault or negligence. (Barham v. So. Cal. Edison 1999). This ruling made these monopolies the funding source for losses that can result—at least in part—from the actions of others. This has further increased utility customers’ cost burden.

This policy has affected utilities in several ways. They have paid enormous damages for tragic conflagrations that killed dozens of people and destroyed numerous homes and buildings. Utility operations and investments have been altered toward more aggressive tree trimming and power line upgrades, including the expensive burial of power lines. Customers have been subjected to planned power outages at times of especially high fire risk.

The commandeering effects of this policy are challenging to assess. Under any liability standard, electricity-caused fires can be the fault of utilities and cause damages that the utilities should compensate. Clearing vegetation from facilities and maintaining system safety are also part of the business. Therefore, expense increases resulting solely from this initiative may be difficult to estimate, especially when evident risks argue for upgraded efforts and spending.

Also, damages paid by utilities may or may not find their way into electricity prices, either directly as allowed expenses or indirectly through higher insurance premia or the risk of shareholder losses. In the most dramatic instance, PG&E’s stock price fell from its all-time high of $70.88 in 2017 to $3.80 in early 2019 because of wildfire liabilities and bankruptcy. While it seems intuitive for such an outcome to have raised the cost of capital for utility investments, it is not easy to know how much customers may be paying as a result.

Therefore, a lower bound for commandeering’s fire-related cost may be the money set aside to cover future damages: $855 million in 2023 and a similar amount for 2024. On the other hand, one estimate for the utilities’ 2024 fire-related expenses is $5.2 billion for PG&E, $2.0 billion for So Cal Edison, and $484 million for SDG&E—up 90 percent from the start of 2023. At $7.7 billion, that is nearly a fifth of the utilities’ entire revenues for electricity service (Cal Advocates 2024c). If some portion of the additional $6.9 billion does relate to the liability standard, then its commandeering impact is that much greater.

Cross subsidies / California mandates two major types of cross subsidies for consumers: those that fund low-income support programs and those that fund environmental programs.

California’s CARE program funds discounts to low-income beneficiaries, including enrollment and eligibility verification done in-house by the utilities. Monopoly electricity customers were charged program benefits and administrative costs of $1.76 billion in 2023. In this way, the majority of customers pay higher utility bills so their neighbors of lesser means can pay less.

Numerous public programs help low-income people afford the necessities of life, a key role for government. Yet, providing these benefits is not a typical part of doing business for the companies that deliver such necessities, and it seems more appropriate for an on-budget tax-and-transfer government program funded through progressive taxation. Many Californians can use the help, given the high prices they pay for energy and the state’s high poverty rate. However, funding such assistance through commandeering stands in contrast to the usual sources of governments and charities.

The second customer-to-customer support plan is an environmental initiative to boost solar electricity generation. Solar cells have made generating electricity feasible in a backyard or on a roof. In its excitement to embrace this technology, in 2006 California set a goal of installing a million solar roofs—a number that seemed exhilarating at the time, but that has since been surpassed.

Consumers usually pay companies only for the services they supply and don’t pay other consumers for providing their own services. However, California requires such funding for solar customers in two main ways, in addition to the federal solar tax credit. The result is that ratepayers without solar roofs are charged more to finance large discounts for those who have them.

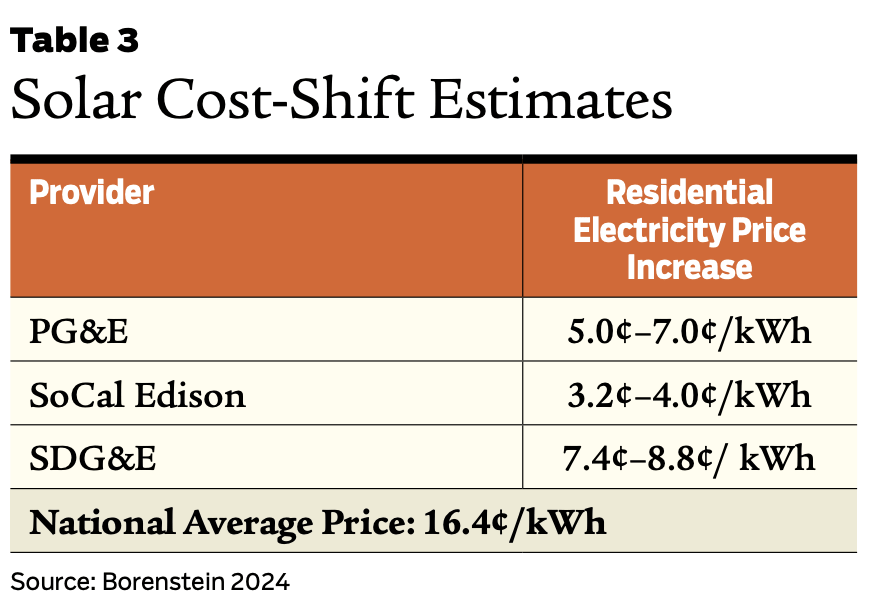

These higher charges take two forms. First, solar customers tend to stop paying usage fees for electricity as their net purchases shrink or fall to zero. Yet, the utilities’ non-electricity costs such as poles and wires (the majority of their expenses) are mainly collected through those same usage fees. Non-solar customers are left picking up the tab for the costs the solar customers avoid. Second, solar customers get paid for excess electricity they send to the grid when the sun is high, and those payments have been generous. The tax credit plus these funding sources have allowed home generation to pencil out, even though electricity generated on a roof is about three times as costly as from a large solar farm (Lazard 2024). Across all three utilities, non-solar customers will pay an extra $6.5 billion to support their solar neighbors in 2024 (Cal Advocates 2024b, Borenstein 2024).

The variable pricing structure has been popular for some other reasons, and a recent reform has reduced payments for excess electricity fed into the grid. But regardless of tinkering to address financial pressures, the notion that utilities should help pay for customers’ solar systems remains California government policy, implemented by commandeering the utilities’ private monopoly power.

Total revenue effect / Together, the three utilities had nearly $40 billion in revenue in 2023 (CPUC 2024). As an approximation (combining some 2023 and 2024 figures), the totals from these commandeering effects were $2.6 billion for added program spending plus $8.3 billion for customer-to-customer subsidies. While these figures don’t translate directly into prices, they are an impressive proportion of the $40 billion aggregate that is paid across the economy by residential, commercial, and industrial customers. Regarding one major element, Table 3 reports 2024 estimates for the solar subsidy price impact as paid by home customers without panels on their roofs. (Borenstein 2024). In San Diego (where rooftop solar is most popular), the increase is fully half the national average electricity price.

Commandeering and Social Media Censorship

Litigation and the releases of the “Twitter Files” have confirmed what was once regarded as a far-fetched conspiracy theory: Government can carry out extensive, organized censorship of politically sensitive information through its control over major social media companies. The latter possess “social market power,” the ability to be a viewpoint maker rather than just a viewpoint taker. These companies don’t just convey national conversations about issues, they help shape them.

In recent years, high-level federal officials commandeered social media market power when they asked, persuaded, and threatened companies like Twitter, Facebook, Google, and LinkedIn to shut down user accounts, remove disfavored posts, and reduce the availability of other information on topics such as the origins of the COVID virus, the effectiveness of vaccines, the reasonableness of vaccine mandates, the integrity of elections, climate change, gender debates, abortion, economic policy, and even a parody making fun of President Joe Biden’s family. Among the agencies involved were the White House, the Federal Bureau of Investigation, the Surgeon General, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency. The ill-defined terms “misinformation” and “disinformation” featured prominently in these campaigns, referring to expressions that federal officials desired the public not view (Missouri v. Biden 2023a, Missouri v. Biden 2023b).

As examples of pressures that were brought both privately and publicly, President Biden’s press secretary threatened a “robust anti-trust program” as a potential consequence for social media platforms failing to cooperate with administration demands. The White House communications director also threatened adverse amendments to Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, which gives online media companies immunity, as platforms, for the contents of third-party posts. Either of these actions could greatly harm social media firms (Missouri v. Biden 2023a, Missouri v. Biden 2023b).

The Supreme Court acknowledged this use of power even as it overturned an appellate court’s injunction against senior government officials and agencies for these activities. The Court found the evidence and findings in the case thus far did not justify an immediate order against future censorship of these plaintiffs by federal officials. In part, this reflected the Court’s concern about distinguishing the results of governmental pressures from the content moderation policies the companies operate on their own authority and judgment. However, the Court’s opinion conceded that the government played a role in at least some of the platforms’ content moderation decisions. (Murthy v. Missouri 2024). Regarding Commandeering Theory, that’s enough. The platforms exercised their social market power both on their own account and at the government’s behest.

What was legal about these practices is still being argued. The Supreme Court has already discussed an important First Amendment distinction between the government acting to limit speech versus the government’s own right to speak disapprovingly about viewpoints it disagrees with. After all, public policy involves persuasion, and public officials should speak out about matters of concern that can include material on social media. Politics also legitimately involves pressures and threats of consequences. Also, the confidential sharing of sensitive information between government and private entities, such as regarding cyberthreats or illegal actions by third parties, is often appropriate for fighting crime and enhancing national security. Distinguishing between commandeering and the above can be a matter of judgment.

Regardless of how these legalities are sorted out, the scale of major social media companies gives them social market power that their smaller competitors do not match. That scale is what recommended them to a government wanting to exercise that influence for itself beyond the usual actions of governance and politics mentioned above. At least some of their resulting engagement and pressures amounted to commandeering.

Theories of Regulation: Where DoesCommandeering Come From?

As government regulation expanded during the 20th century, so did explanations about its extent and workings. Here are some well-known theories:

- Public Interest Theory: Regulation addresses monopolies, externalities, public goods, and other problematic circumstances that market forces may fail to correct.

- Special Interest Capture: An industry gains control of its regulator, to act for the industry’s advantage.

- Public Choice Theory: People in regulatory agencies steer the agency’s actions to benefit themselves.

- Bounded Rationality: Regulation corrects for information asymmetries, biases, short-termism, or flawed reasoning by firms or the public.

- Momentum of Institutions: Entrenched procedures and rules lead agencies and courts to act as they always do.

- Bootleggers and Baptists Theory: Political coalitions enact rules to advance their ideologies and economic interests.

- Taxation by Regulation: Regulators have some customers pay more so others can pay less for a service or product.

I propose that Commandeering Theory be added to this list. In a nutshell, this new theory holds that government can use its regulatory authority to pressure or require a firm to exercise its influence to fund desired projects or shape customer behavior. Both the electricity and social media examples fit this model.

What are some possible motives for commandeering?

- It can be easier politically to use a third party’s monopoly power to raise revenues for a governmental purpose than to enact a tax increase.

- Government programs associated with a company’s service may seem more politically acceptable than stand-alone efforts.

- Implementation can be eased if a third party already has helpful systems in place (e.g., for billing), and directing its staff to carry out a program can be simpler than setting up a government operation to do the same.

- Blame for harm caused by the initiative may be aimed at the commandeered private party (e.g., high electricity bills are “the utility’s fault”).

- If a third party has capabilities the government lacks and cannot develop, commandeering may be the only way to achieve a desired goal (such as widespread censorship through social media companies).

- If only a few influential third parties need to be influenced, then commandeering may minimize communication and coordination issues for government.

Costs and benefits / Does regulation through commandeering harm the public? The answer may depend on the comparison being made, as any such evaluation must contrast two (or more) possible alternatives.

Perhaps there’s a policy that isn’t feasible except through commandeering. Then, we would start with the public being hurt by government’s use of private entities’ monopoly or social market power against consumers. That harm would be set against the benefits and costs the policy produces, with the cost–benefit baseline being no policy at all.

Secrecy may matter. Clandestine commandeering through pressure or threats (as with social media censorship) may make it easier for government to take problematic actions, again to be contrasted to a “no policy” baseline.

Another comparison is between a policy using commandeering and a similar policy put in place in another manner (perhaps as described in another regulatory theory). Unhappily, the operation of many of those other theories can create problems, and there has been no shortage of folly and foolishness in policies brought about in a variety of ways. There is also no costless way to raise money for public purposes, and the marginal cost of public funds obtained through some forms of taxation (for example) may be as high as for monopoly price increases. So, commandeering may not always be the worst way to achieve a policy goal.

At the same time, some program objectives may be desirable even if pursued through commandeering, such as California’s low-income subsidy. Proponents for the other California efforts often use this justification, and enabling legislation or regulatory decisions tend to include findings of need and public benefits (even if a critical assessment may conclude otherwise). Maybe commandeering can sometimes be the only way (if a costly one) to achieve something worthwhile.

On the other hand, government officials may mistake costs and benefits. Consider that in California, reduction of energy use (as opposed to pollution) is sometimes seen as an end in itself. Ironically, this error undercuts one of the bedrock justifications of monopoly regulation: to not reduce the value of a good by pressuring customers to give up usage they desire or need.

To conclude on this question: Although commandeering may start at a substantial deficit in any cost–benefit analysis, I don’t see a general tendency for its results to be better or worse than regulation produced by other explanatory theories.

Posner? / Finally, I note Richard Posner’s “Taxation by Regulation” analysis, the last of the regulatory theories listed above. Posner highlighted the cross subsidies found throughout regulated industries to give low prices to selected consumers. Sustaining these requires charging more to other buyers, potentially including barring competitive entry into the higher-priced lines of business to protect the source of funding. Posner saw this approach as a substitute for general taxation and spending.

Is Commandeering Theory a variant of Posner’s theory? The two share the use of monopoly power against consumers to fund a political priority. Under both theories, a regulatory ruling may be a less politically troublesome (and less transparent) means to fund some activity that might not survive a legislative tax-and-budget process.

However, one difference is Posner’s emphasis on service price discounts by the firm versus commandeering funding activities the regulated firm ordinarily might not pursue at all. Also, the social media example shows commandeering going beyond economics to co-opting other powers or influence that private entities may have.

This difference might point to a further risk: Commandeering may promote corruption. The need to inhibit competition to preserve the source of funding for intra-company cross subsidies can be one form of bending public policy to protect the government’s own objectives, in Posner’s description and much personal experience. In return for a company taking a commandeering action, regulators also might use their discretion to provide a quid pro quo in a seemingly unrelated oversight decision. But at least Posner’s regulated company is operating its own business and the needed cash flows are distant from the hands of any public officials. For commandeering like the social media case—involving core political objectives, hands-on involvement by public officials with those making corporate operating decisions, and secrecy—the potential seems greater for private entities to be given improper benefits from the government in return for their cooperation.

Conclusion

It is tempting for government officials to commandeer an influential third party to pursue a policy goal. And in our examples, neither federal nor California authorities have seemed concerned about causing harms they are normally supposed to avoid. California’s commandeering has proceeded in the open, with consistent political support for priorities whose subtleties can be complicated. However, Californians are starting to question the high prices they are paying for energy, and perhaps some rethinking may occur.

For its part, the federal government is still trying to portray its censorship enterprise as benign and appropriate, despite revelations that complicate that stance. While these actions have become a national issue, it may still be some time before politics and the courts clarify where government’s right to criticize crosses the line into social media censorship that government is forbidden to attempt.

Readings

- Barham v. Southern California Edison Co., 1999, 74 Cal. App. 4th 744.

- Borenstein, Severin, 2024, “California’s Exploding Rooftop Solar Cost Shift,” Energy Institute Blog, Haas School of Business, University of California, Berkeley, April 22.

- Cal Advocates (Public Advocates Office, California Public Utilities Commission), 2024a., “Rooftop Solar Incentive to Cost Customers Without Solar an Estimated $6.5 Billion in 2024,” February 28.

- Cal Advocates (Public Advocates Office, California Public Utilities Commission), 2024b, “2023–2024 Wildfire-Related Cost Increases of California’s Three Major Investor-Owned Electric Utilities,” June 14.

- Cal Advocates (Public Advocates Office, California Public Utilities Commission), 2024c, “Q2 2024 Electric Rates Report,” July 22.

- CPUC (California Public Utilities Commission), 2023, “Decision Adopting Timing and Amount of 2024 Wildfire Fund Non-Bypassable Charge,” D. 23–11-090, December 4.

- CPUC (California Public Utilities Commission), 2024, “2023 California Electric and Gas Utility Costs Report.” April.

- Edison (Southern California Edison), 2024, “Tiered Rate Plan.”

- EIA (Energy Information Administration), 2024, “Electric Power Monthly: Table 5.6.A Average Price of Electricity to Ultimate Customers by End-Use Sector,” June.

- Lazard, 2024, “Levelized Cost of Energy+,” June.

- Missouri v. Biden, 2023a, 662 F. Supp. 3d 626.

- Missouri v. Biden, 2023b, No. 23–30445 (5th Cir.).

- Murthy v. Missouri, 2024, 603 U.S. ___.

- PG&E (Pacific Gas & Electric Co.), 2024, “Residential Rate Plan Pricing (effective September 1, 2024).”

- Posner, Richard A., 1971, “Taxation by Regulation,” Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science 2(1): 22–50.

- SDG&E (San Diego Gas and Electric), 2024, “Schedule DR, Residential Service (effective March 1, 2024).”

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.