Donald Trump ran for president in 2016 promising he would be “cutting regulation at a tremendous clip. I would say 70 percent of regulations can go.” When he left office in 2021, he claimed to have “slashed more job-killing regulations than any administration has ever done before.” Is Trump’s record on regulation an example of, to borrow one of his slogans, “promises made, promises kept”? Or is it just a politician’s rhetoric?

On first glance, the answer is unclear. Clyde Wayne Crews, a regulation expert at the Competitive Enterprise Institute, writes:

During Trump’s four years, there had been some unique reversals, such as a slowdown in the issuing of new rules and some rollbacks of existing ones. … At the same time, many of Trump’s actions imposed rather than decreased burdens, including trade interventions like tariffs, anti-dumping and “Buy American” agendas, and domestic regulatory interventions.

So, what was the net effect of Trump’s administration on federal regulation? His supporters claim that he deregulated, even if most of his administration’s actions were administrative and were rapidly canceled by his successor, Joe Biden. The question is difficult to answer because there is no objective way of measuring total regulation. Still, there are data that can give us a decent picture of Trump’s regulatory record.

Regulatory burden / The Trump administration famously introduced a “one-in two-out” goal of abolishing two existing regulations (technically called “rules”) for every new one implemented. That seemingly would guarantee the federal regulatory burden would decrease. Yet, a major new regulation may be more consequential and burdensome than two minor ones that have been abrogated. So, what were the results of the Trump administration?

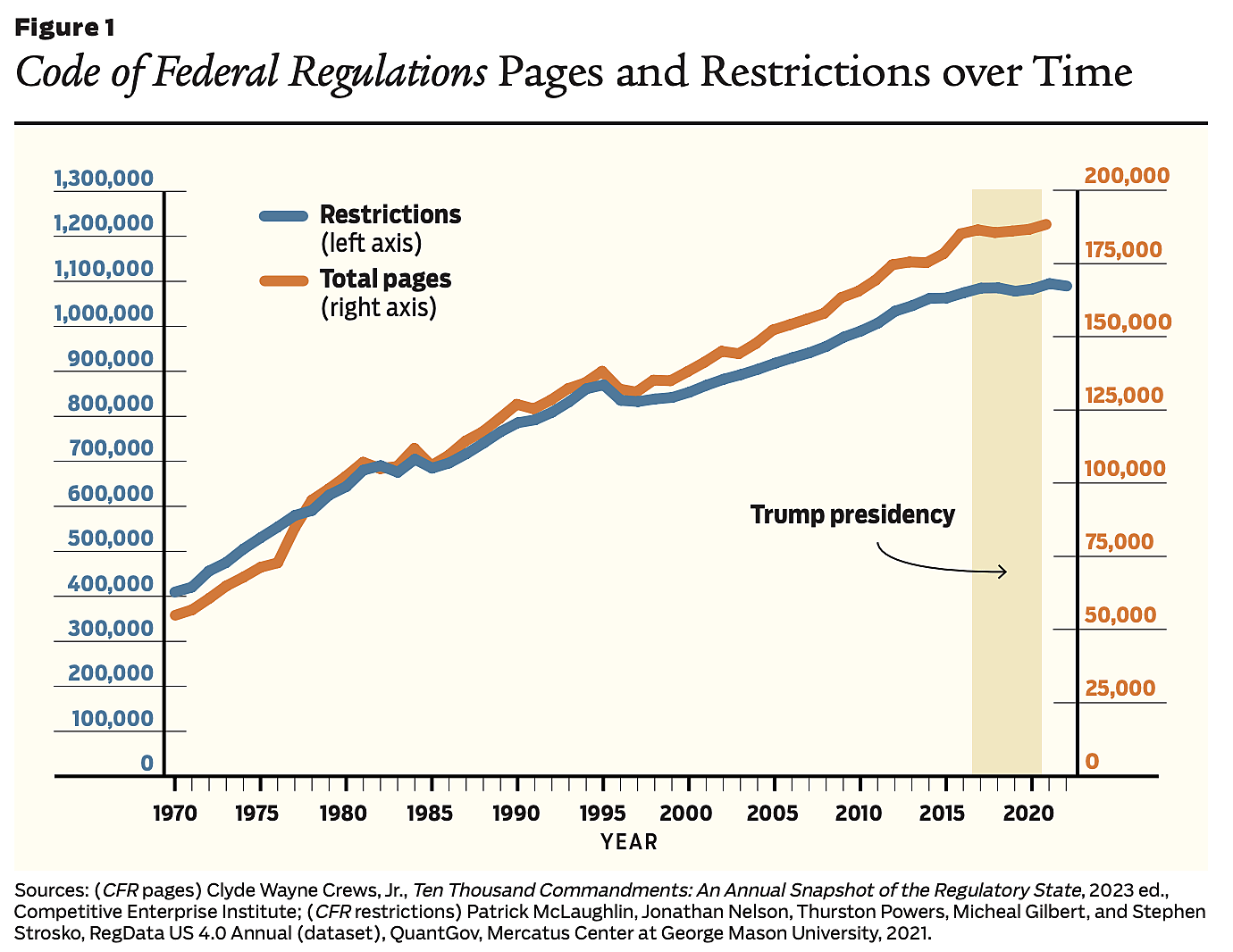

There are some indirect indicators of the level of federal regulation. One is the total number of pages of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), the existing stock of all federal regulations. A reasonable conjecture is that if the regulatory burden increases on net, the number of pages of the CFR would increase—and mutatis mutandis if the number of pages decreases. Admittedly, it is a rough indicator.

A new and more sophisticated measure of federal regulation, devised by economists at George Mason University’s Mercatus Center, consists in counting the number of CFR “restrictions” indicated by the keywords “shall,” “must,” “may not,” “required,” and “prohibited.” Interestingly, both the CFR page count and restriction count show a strikingly similar evolution of federal regulation, bolstering our confidence that they provide a reliable indicator of the phenomenon.

Figure 1 compares the two series since 1970. The total number of CFR pages, measured on the right vertical axis, was 54,834 at the end of 1970, and 188,346 at the end of 2021 (the last year available). The number of restrictions, measured on the left axis, stood at 409,520 in 1970 and increased to 1,089,462 by 2022. Both measures show a nearly non-stop rise in federal regulation, with only very short periods of deregulation. The two series don’t exactly match but show similar bumps in the trend.

Trump’s record / These data help us evaluate Trump’s claim to be a deregulator. Both indicators show a rough plateauing of the upward trend, with a very small increase between the last year of Barack Obama’s administration (2016) and the last year of Trump’s (2020). Between these landmark years, the number of pages in the CFR increased 0.8 percent (to 186,645), as did the number of restrictions (to 1,083,001). According to both series, then, the net effect (new regulations, including deregulatory rules, minus abrogated or simplified ones) of the Trump administration has not been deregulation but, at best, a plateau in the upward historical trend. At best, 0 percent of federal regulation did “go,” to use Trump’s expression.

These data don’t include what Crews calls “regulatory dark matter”—that is, instead of formal rules, administrative documents such as executive orders and memoranda and, from different government agencies, guidance documents, bulletins, circulars, etc. The Trump administration had started a process of publicizing guidance documents and recognizing their non-legal character, but the Biden administration stopped that. The conclusion remains that the Trump administration presided over a plateau in the growth of formal federal regulation, not deregulation.

Interestingly, Figure 1 is ambiguous as to the regulatory trend of the Biden administration. So far, the volume of new regulations has been relatively low, but it should soon jump given the administration’s ambitious interventionism. Everything points to a decisive return to galloping regulation with less oversight from the Office of Management and Budget. One suspects that a second Trump administration would have followed a similar trajectory, although perhaps not with the same ferocity.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.