The United States has officially surpassed 1 million deaths from COVID-19, a shocking number that was unimaginable two years ago. Those aged 65 or older account for about 750,000 of those deaths. This age distribution raises the question, should the concentration of the deaths among older people affect how we value those deaths?

Identifying fair and economically correct treatment of seniors is difficult for two reasons. First, the recent pandemic has been much harsher on the elderly compared to previous pandemics; for example, the elderly comprised only 1% of deaths in the 1918 flu pandemic. Second, because seniors have shorter life expectancy, it has been suggested that we apply a different economic weight to their loss of life as compared to younger people.

VSL / Focusing on the amount of remaining life offers the allure of quantitative precision but does not address the right economic issue. What matters is how much those affected and society in general are willing to pay to reduce the risks. Should we be willing to pay more, less, or the same to extend the life of an elderly person compared to a younger person? How do economists and government agencies put a dollar value on something as precious as risks to a human life?

The answer lies, in part, in the public policy literature that examines the Value of a Statistical Life (VSL), by which economists estimate how much money people are willing to pay (or be paid) to accept or evade small changes in the risk of death. Analysts use VSL estimates to infer an implicit value of life extension. In particular, workplace studies have examined how much more workers have to be paid to take jobs with higher fatality risk (e.g., test pilots versus airline pilots or underground mining versus above-ground mining). Economists have also studied how much individuals are willing to pay for safety improvements such as airbags or bicycle helmets, which reduce fatality rates or injuries.

Elderly COVID deaths / In the United States, there is considerable evidence across numerous product and labor market settings that, on average, people are willing to pay about $110 for every 1 per 100,000 reduction in fatality risk involved in working or using a product or service. So, as a group, 100,000 people are willing to pay $11 million for a safer job, product, or life-saving service that would prevent one death from injury or disease. Because the specific life saved would not be known beforehand, this is called a “statistical life,” which then yields the VSL. The $11 million number is similar to the values that the federal Environmental Protection Agency, Department of Transportation, and Department of Health and Human Services apply to the benefits of a life saved.

With rare exceptions, government agencies use the same VSL to value mortality risks of populations irrespective of age, gender, income, the type of death, or other characteristics. A notable case where government agencies made an age adjustment was in the EPA’s 2003 analysis of the Clear Skies Initiative, a proposal to regulate power plant air emissions, in which the agency applied a 37% discount to the VSL applied to mortality risks for those aged 65 and over. After a public outcry and complaints from senior citizen organizations such as the AARP that seniors’ lives were wrongly being devalued, the EPA abandoned the practice of adopting any senior discount.

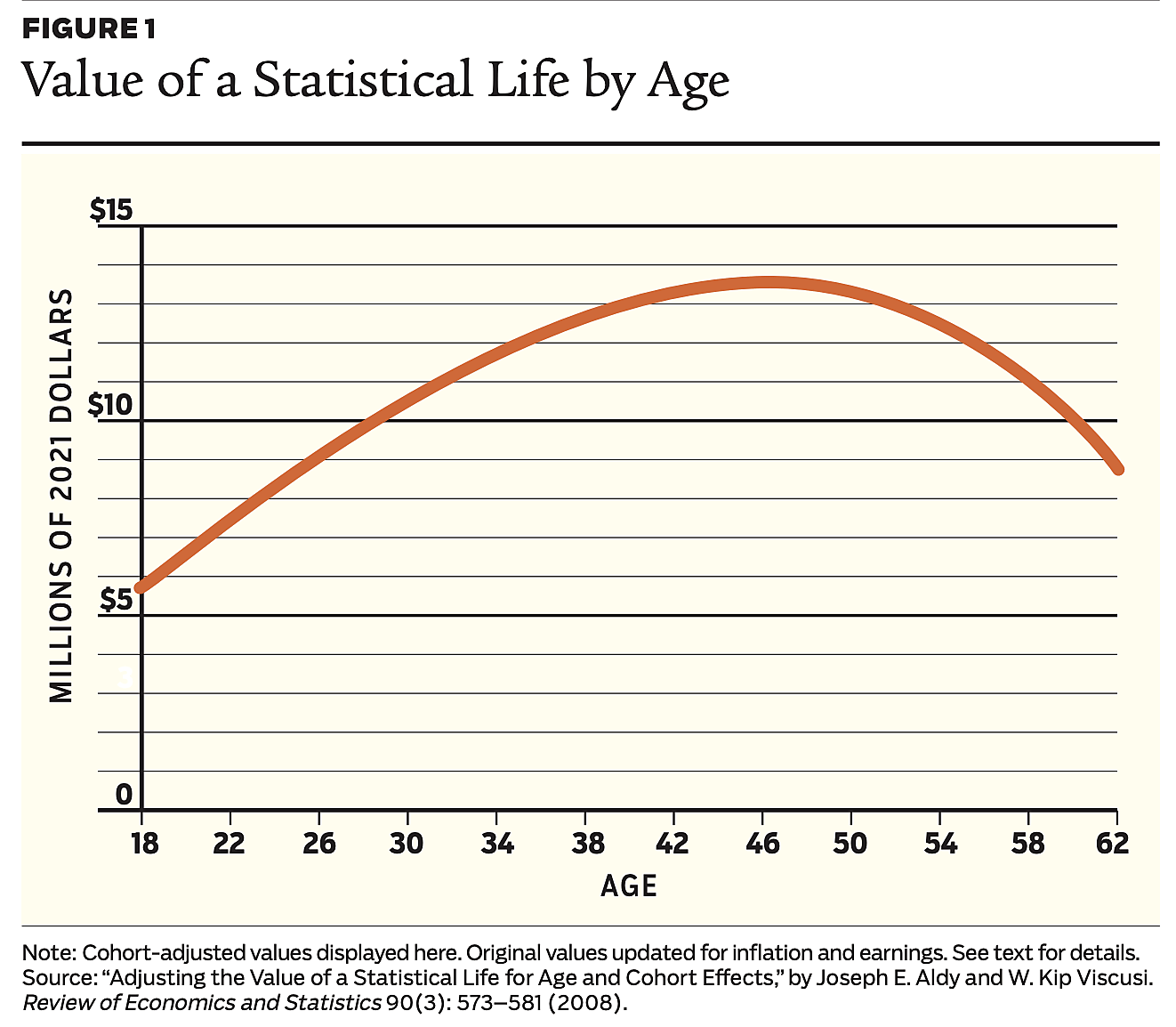

Yet, people often behave as if there are differences, given who is dying and the type of death. Although the average VSL may be about $11 million, aggregated data of workers’ revealed VSL typically form a hump shape over the life cycle. People’s willingness to pay to reduce their risk of death increases as they mature and then declines as they approach old age. See Figure 1.

The greater affluence of older Americans and their lower willingness to accept risks affect their estimated VSL. For example, the estimated VSL in the United States for people aged 55–62 is not materially different than for those aged 18–25. The public outcry over the senior discount used in the Clear Skies Initiative regulatory impact analysis may reflect a societal reluctance to devalue the lives of older people even if their private values are not as great as they were in their 40s.

Determining whether the VSL should be the same for older people or if there should be age variations in the VSL can have practical implications in the allocation of medical resources. For instance, while ventilators currently are not as scarce as when the pandemic emerged, it is likely that society will have to confront comparable allocation decisions in future health crises. There are also interim near-term decisions that will be affected, such as assessing whether it is worthwhile to have a reserve of ventilators and other medical facilities to address potential future surges in illness. Whether such anticipatory efforts are desirable hinges on whether the lives that will be extended are accorded a substantial value. If the beneficiary group is older people and their VSLs are discounted, then there may be little inclination to prepare for future pandemics.

In what is sometimes termed a “fair innings” approach, some ethicists have suggested that young people should be given priority for life-saving measures such as ventilator access. The stated ethical rationale is that older people have already had their “turn at bat.” Some analysts have offered support for such an emphasis by tallying the number of life years at risk rather than considering the willingness-to-pay amounts. This life expectancy table approach ignores the private benefit values reflected in the VSL, which are grounded in the person’s own willingness to pay for the benefit. If peoples’ valuations do not plummet with age, then there is no economic rationale for discounting older people’s lives.

The estimates depicted in Figure 1 suggest that if we choose to use lower VSL values for the elderly, then we should do the same for the younger population groups in society that have a similar valuation for their (statistical) life. Should we use a lower VSL in cost–benefit analyses for children’s vaccination campaigns or when making decisions to protect young soldiers in the military? Using different VSL values across different age groups creates difficult theoretical and moral dilemmas for policymakers, which is a main reason why policymakers have been reluctant to use such age-based adjustments.

Dread / If we choose to adjust the VSL by age, then we should consider adjusting it for other factors as well. For instance, one of the biggest potential adjustments for both the mortality and morbidity effects of a disease such as COVID is dread. Particularly dreadful diseases have been found to dramatically increase the VSL, as people report that they are willing to pay more to reduce their risk of death from dreadful diseases in comparison to more “normal” fatalities such as car accidents.

For example, researchers have found that cancer deaths (which are often skewed toward the elderly) have a VSL premium roughly 21% higher than normal deaths, indicating that people would be willing to pay more to avoid that type of death in comparison to similar fatality risks in society. Other VSL premiums have been found in severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), terrorism, and deaths related to influenza. One study put the VSL premium for SARS as high as 435% in comparison to so-called normal deaths.

Should we be making such VSL adjustments across different age groups and different disease types? Making this determination requires finding precise willingness-to-pay estimates corresponding to the VSL. A new disease such as COVID does not have a long list of studies that coalesce around a specific VSL value. It may take years to get to that point. Until the literature becomes more advanced, it makes sense to stick with the default value of the population-average VSL.

Cost-effective policies / If we do conclude that there is no reason to undervalue the lives of the elderly when making policy, what would be part of an economically fair policy for the next pandemic, which may again disproportionately affect the elderly?

Of course, reducing the bureaucratic barriers that slowed the development and administration of a vaccine and widespread testing of the elderly would be obvious components of cost-effective policy. Regulations on outdoor activities do not appear to be part of economically sound policy. Regulations on outdoor dining, for example, save relatively few lives. In addition, recent evidence indicates that socially isolating the elderly to decelerate the spread of COVID has important negative consequences for their mental health.

Another policy implication could lie in the quickly expanding interest in what are called the social determinants of health. Although then–New York governor Andrew Cuomo said that nobody’s mother was expendable, his decision to move older patients with COVID into nursing homes appears to have accelerated its spread among the senior population, exacerbated by nursing homes with staffers working at multiple locations.

Aging in place / In a recent national survey, about two-thirds of Americans said they hope to “age in place”—that is, spend their senior years in their homes instead of some seniors facility. But only about one-third of the respondents believe they actually will do this.

Two prominent obstacles cited for this gap between hopes and expectations were concerns over not having enough money saved and poor tech literacy. One longer-run policy potentially emerging from the pandemic might be a greater embrace of the aging-in-place model where more resources (possibly from Medicaid) or different technologies—such as video health provider visits—help keep more people in their homes as they age.

For these and other policies that affect the elderly, the valuation of the benefits should not revert to a simple count of the expected remaining years of life. Such tallies are divorced from the fundamental economic principles for assessing regulatory benefits. The principal driver of mortality benefits is how much affected people value the policies. Application of the VSL remains the correct economic approach.

Readings

- “Adjusting the Value of a Statistical Life for Age and Cohort Effects,” by Joseph E. Aldy and W. Kip Viscusi. Review of Economics and Statistics 90(3): 573–581 (2008).

- “New Estimates of the Value of a Statistical Life using Air Bag Regulations as a Quasi-Experiment,” by Chris Rohlfs, Ryan S. Sullivan, and Thomas J. Kniesner. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7(1): 331–359 (2015).

- Pricing Lives: Guideposts for a Safer Society, by W. Kip Viscusi. Princeton University Press, 2018.

- “Pricing the Global Health Risks of the COVID-19 Pandemic,” by W. Kip Viscusi. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 61(2): 101–128 (2020).

- “The Forgotten Numbers: A Closer Look at COVID-19 Nonfatal Valuations,” by Thomas J. Kniesner and Ryan S. Sullivan. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 61(2): 165–176 (2020).

- “The Value of a Statistical Life: Evidence from Panel Data,” by Thomas J. Kniesner, W. Kip Viscusi, Christopher Woock, and James P. Ziliak. Review of Economics and Statistics 94(1): 74–87 (2012).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.